Abstract The contribution explores the migratory situation on the Balkans and more specifically in the so-called Refugee District in Belgrade from a spatial perspective. By visualizing the areas of tensions in the Refugee District, the city of Belgrade, Serbia and Europe it aims to disentangle the political and socio-spatial levels that lead to the stuck situation of in-betweenness at the gates of the European Union.

Keywords Balkan route, European border regime, mapping, migration, urban development

In December 2017 and September 2019, we visited Belgrade in Serbia, a country at the edge of the European borders. Both times, we researched the so-called Refugee District and faced a state of exception and normality at once; a situation that has been going on for years. As the European border regime is gradually closing its borders, instead of dealing with the actual causes of migration, a rising number of people on the run and migrating find themselves in a desperate situation. Coming from somewhere else, they are in search of a place in peace, safety, and better perspectives in Western Europe. In Serbia, they are living in limbo, waiting for a possible continuation of their uncertain journey that potentially will never be fulfilled.

We come from a German, white, and academic context. This background shapes the perspective we take for reflecting on our role within the EU in relation to the situation in Belgrade. In this sense, we are dealing with the question of how this stuck situation, which is especially visible and tangible in the Refugee District, could arise, and how it is produced and challenged by practices of refugees, the urban development of Belgrade, the Serbian migration management, and (inter)national and European migration policies. The Refugee District in Serbia, thus, serves as a starting point for decoding and disentangling the situation at this specific place outside of the EU but within the EU border regime from a political and socio-spatial perspective.

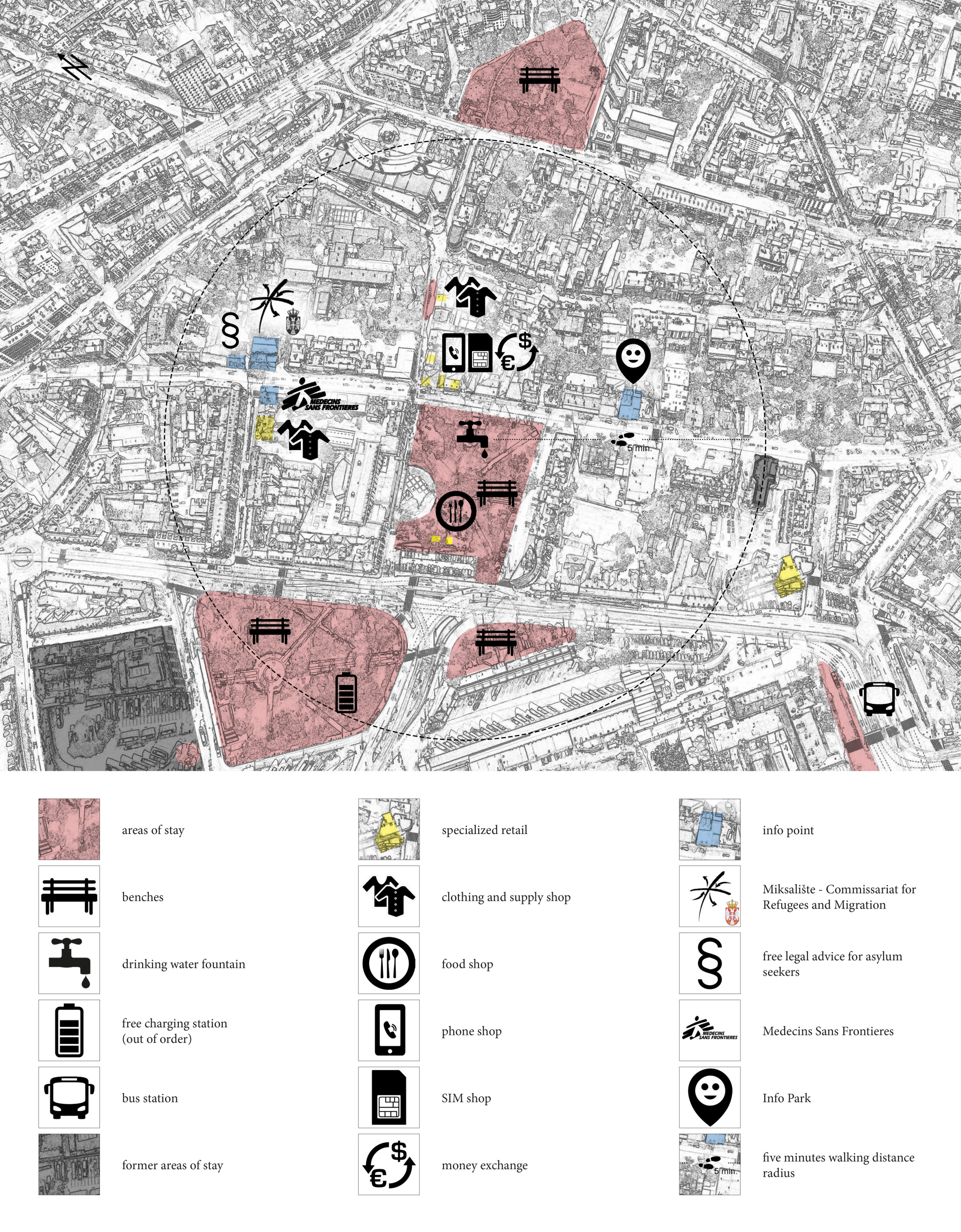

The Refugee District is located in the heart of Belgrade, Serbia. Since 2014/2015, it became a hub for refugees on their route through the Balkans. Not only due to its close proximity to main transport facilities and related infrastructures supporting travel but also due to the location of many humanitarian aid organizations and even flight related services, the district functions as a place for refugees. It constitutes a space for information, networking, travel preparation, and for awaiting the ›game‹, the irregular migration towards the EU. Its physical structure, including parks with benches, a water supply, and abandoned houses facilitates practices of talking, eating, shopping, praying, sleeping, etc. But the refugees’ practices and the supporting infrastructure are threatened by the demolition and decay of places as well as people being prohibited to use certain spaces. Also, the NGOs’ work that includes medical treatment, information, free spaces, law advice, and more is restricted and controlled by prohibiting them to support people in the streets and those who are not willing to be registered. Despite attempts to restrict and regulate the infrastructure for, and the presence of, refugees in the Refugee District, refugees have been appropriating spaces in the centre of Belgrade for years: they have claimed their right to be there and to continue their journey towards the EU. They constitute a »non-movement« (Asef Bayat) for a global freedom of movement. The Refugee District can be seen as a condition as well as product of their practices, which is constantly undergoing changes depending on environmental, social as well as political processes on the urban, national, and transnational scale.

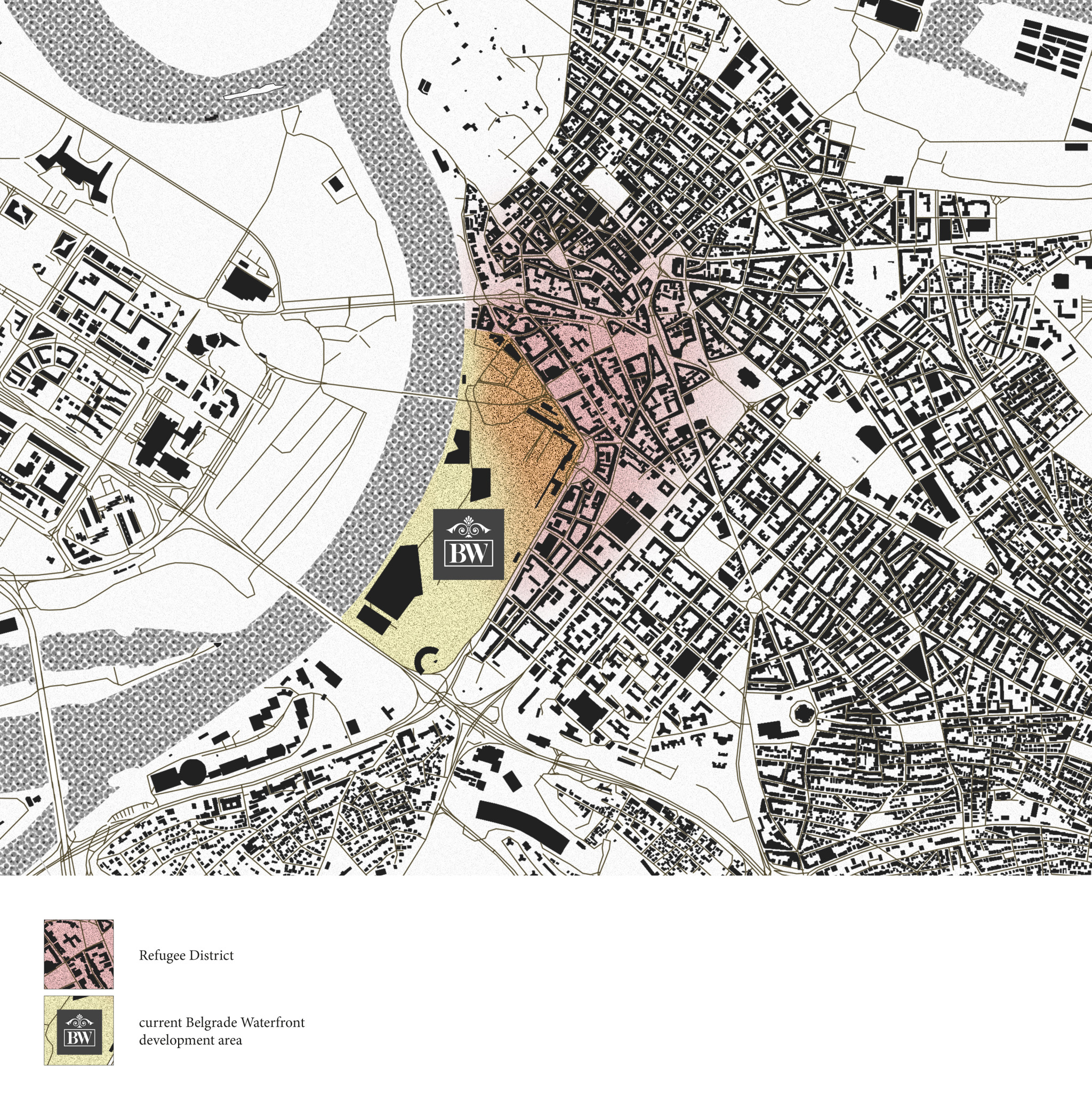

Looking at the issue from an urban level, the neoliberal development of the city politics inevitably becomes apparent. Belgrade, as a city within the context of globalisation and its competition between cities, is under pressure to expand and valorise its economic potentials in order to increase the private accumulation of capital. The current project Belgrade Waterfront is the dominating incarnation of this development. While step by step this megaproject in the city centre of Belgrade is planned and realised, refugees are passing through Belgrade. Their way of appropriating public space is classified as informal and precarious, which does not fit to the image of an entrepreneurial city and, hence, should be made invisible to the public eye. Their displacement in terms of space (e.g. through the demolition of inhabited abandoned barracks and houses or their expulsion from public space), society, and discourse leads one to presume an existing relation between the neoliberal developments and the intention to banish them from this area. The ongoing construction site and the ceased maintenance of spaces, though, constantly offer new niches. The refugees appropriate those places and thereby express their inevitable presence and right to freedom of movement. Thus, the Refugee District shows that flight, refugees, and their spatial impacts cannot be rendered invisible in the city.

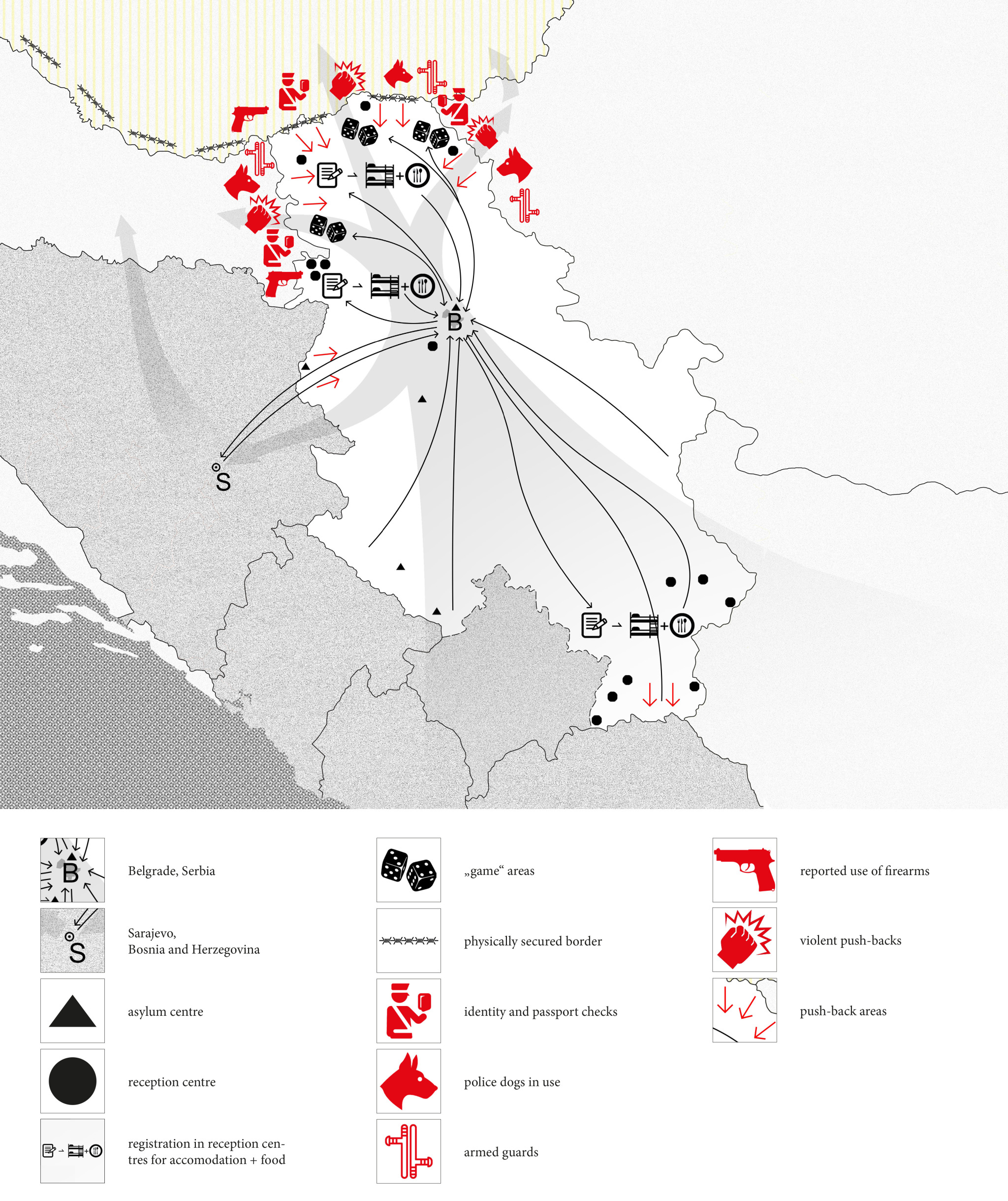

Serbia is perceived and positions itself as a transit country. It is, though, not experienced as such by refugees who have to wait for months and even years in reception and asylum centres in order to proceed their journey to the European Union. The Serbian migration management reacted—with institutional and financial support from the European Union—with a closure of the EU’s external borders. There is a tendency towards professionalising the management of migration (in terms of accommodation, integration measures, such as the schooling of children, etc.). Within this context of migration management, the Refugee District, as a hub for migration on the Balkan route, serves as a central place for registering and transferring people into governmental structures. Therefore, Serbia has expressed the need to control the flow of information, which can be observed in governmental actions restricting places and activities of self-organisation between refugees and other people as well as with the take-over of the formerly privately-run NGO Miksalište in the district by the Serbian government. The Refugee District equally constitutes a place of departure for the ›game‹, for those who try to cross the border irregularly. In the context of Serbian migration management, pictures of refugees and a state of crisis help to uphold international financial support. Only by ignoring the ›game‹ and the Refugee District’s central role in it, transit can remain possible for refugees and, consequently, Serbia’s position as a transit country. Its positioning as a transit country is further enabled by the increasing role of Bosnia and Herzegovina as an entering point to Croatia since 2018. People try the ›game‹ via Bosnia and Herzegovina and even come back to Serbia because the accommodation structures are better. Within this context, the Refugee District still serves as a hub in this enlarged space of informal mobility in the Balkans.

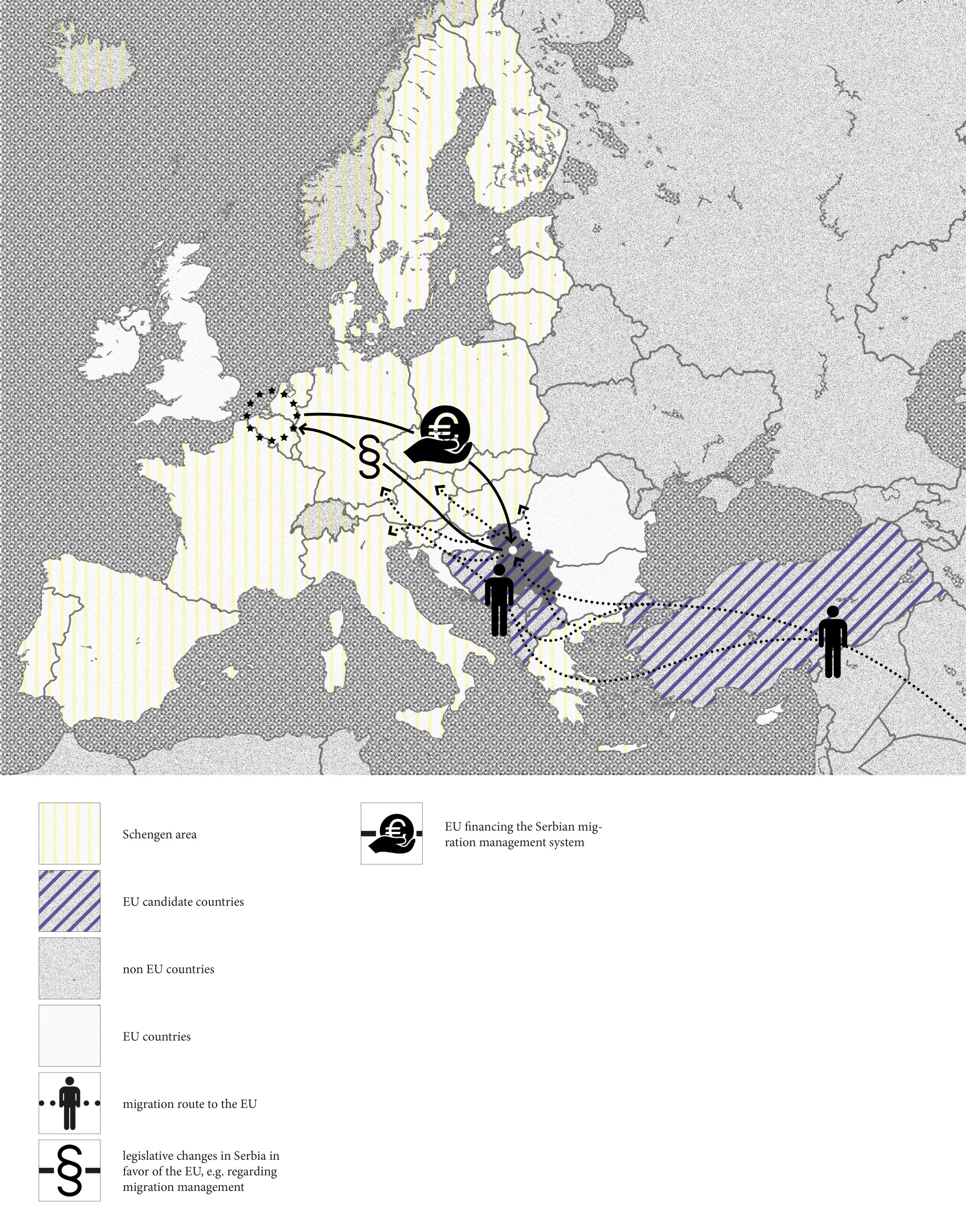

Serbia directly borders on EU-states and is, thus, located between the countries of origin and destination countries of refugees—the Balkan route. This specific location impacts its geopolitical relevance: while the Schengen Agreement facilitates more and more freedom of movement within the EU, the need to isolate itself from the outside is increasingly regarded as necessary. Within the context of migration towards the EU in the 1990s, the term ›externalisation‹ was coined in reference to EU-migration policy. The EU systematically outsources border control and dealing with ›illegal‹ migration to local authorities and, thus, evades respecting civil rights by passing the task to others. The externalisation of European borders is often observed in relation to African countries like Tunisia or Libya, although similar practices can be traced in Serbia. In Serbia’s case, the processes are highly influenced by Serbia’s own interest in becoming an EU member state. Hence, during the ›formalised corridor‹—the temporal formalisation of irregular migration in participating countries along the Balkan route—Serbia was motivated to act in a relatively humanitarian way in order to present itself as an organized state respecting human rights. As soon as the formalised corridor was gradually closed by the EU, Serbia adapted its strategy and performed a ›securitarian turn‹. On the one hand, Serbia acts on its own behalf; on the other hand, the EU wants to codetermine how migration moves through Serbia. By securing the EU border by externalizing it to Serbia’s territory via hard border technologies (like thermal cameras or a fingerprint database), push-backs, and financing the Serbian refugee accommodation and treatment, a huge border space was created in Serbia. Peoples journeys towards the West are limited on behalf of the European border regime and, thus, their freedom of movement. As Serbia itself is in the process of EU accession, it even does not shy away to make legislative changes in order to promote the process. This development has recently been enhanced through EU agreements with Serbia allowing Frontex to assist in border management in the near future. Hence, a correlation has evolved between the European border regime and Serbia that highly shapes the situation of refugees in the country and in the Refugee District in Belgrade.