Abstract This synthetic piece engages the phenomenon of border externalization from the perspective of conflicting maps. On the one hand, there are official cartographies produced by and circulating among policy makers, border authorities, security think tanks and media outlets. While these institutional maps deploy the professionalism and neutrality associated with expertise, we point how they are driven by a restrictive logic of containment towards mobility. On the other hand, we introduce another set of maps, which are just as sophisticated, yet the product of embodied, experiential and activist knowledge(s) coming from those supporting and enacting a politics of freedom of movement. This paper showcases, and reflects on, the politics of institutional maps produced by border institutions used to envision and implement ongoing practices of remote migration control. Attention is further given to examples of counter-cartographies that show how controversial, problematic and inaccurate the institutional maps for migration control are. These counter-maps enable alternative visions and practices of human mobility. Many of these maps are now part of the itinerant art collection first launched in Los Angeles and currently hosted in Zagreb: It is Obvious from the Map!.

Keywords borders, maps, knowledge production, illegality, routes

Migration control increasingly takes place beyond the borders of destination countries. Migrants’ journeys are traced using advanced technology and paramilitary deployments that target migrants’ supposed places of origin and transit. Our work looks at those practices of remote migration control by the European Union (EU), here focusing on official maps by border and security institutions used to imagine and implement this kind of bordering at a distance. Based on a long-term, multi-sited research project (including Brussels, Vienna, London, Madrid, Rabat), this paper1 looks at the cartographic planning supporting externalized EU border practices. We contend that the ›routes thinking‹ behind visual portrayals of migration flows is creating a shared expert language and a geographical imaginary of illegality beyond borders. These maps facilitate a visual logic of tracing migratory routes. Bordering practices along traveling trajectories criminalize movement at its departure and during the transit of a migrant’s itinerary. Illegality is constructed in ways that target border crossing even before any border is crossed, making someone illegal at the very moment and place where s/he decides to migrate.

Our argument builds on bio-political readings of the EU border regime as a producer of distinct clusters of populations with different rights to move (i.e. Feldman 2012; De Genova 2017). We also considerably draw on ethnographic analyses of the EU’s border externalization policies in North and West Africa (Andersson 2014) as well as on ethnographic research on the International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD) (Hess 2010). The ICMPD is the producer and distributor of the »i-Map,« which has played an influential role in visualizing the ›route‹ as an object of policy, disseminating a mapping trend for tracing migrants’ journeys among border institutions. This paper suggests that illegality is cartographically configured and re-configured by ›expert‹ security actors. Such a spatial reconfiguration of borders can have concrete human consequences beyond the maps, giving rise to controversial practices of interception far away from conventional borderlines.

This article approaches the phenomenon of border externalization from the perspective of conflicting maps. On the one hand, there are official cartographies produced by, and circulating among, policy makers, border authorities, security think tanks and media outlets. While these maps deploy the professionalism and neutrality associated with expertise, we intend to highlight how they are driven by a restrictive logic of containment towards mobility. On the other hand, we will introduce another set of maps that are similarly sophisticated, but the product of embodied, experiential and activist knowledge deriving from those supporting and enacting a politics of freedom of movement. This paper showcases, and reflects on, the politics of institutional maps produced by border institutions used to envision and implement ongoing practices of remote migration control. Attention is also given to examples of counter-cartographies, which show how controversial, problematic and inaccurate those institutional maps used for migration control actually are. Furthermore, the counter-maps enable alternative visions and practices of human mobility.2

The maps in this article3 are now shown to the public as part of the traveling art collection »It is Obvious from the Map,« curated by Sohrab Moheddi and Thomas Keenan. It was first launched at The Roy and Edna Disney/CalArts Theater (REDCAT), an interdisciplinary contemporary arts center for innovative visual, performing and media arts located inside the Walt Disney Concert Hall complex in downtown Los Angeles. Currently, the collection is hosted in Zagreb (see Image 1). The itinerant collection includes maps of migratory routes and borders produced by a variety of contesting actors: 1) migration policy institutions, 2) migrants and refugees on the move and 3) no-border activists (see Redcat 2017).

Genealogies of Border Externalization

Over the last five years of the ›refugee crisis,‹ the European Union has increased its bilateral agreements with non-EU countries in order to further contain flows of migration. These agreements double down on an existing EU-approach that relies on collaboration with non-EU countries in matters of border patrol, surveillance, interception and return. This transnational cooperation includes sharing data on border movements and organizing multi-country operations to intersept what are designated as ›migrants in transit.‹ FRONTEX (the ›European Border and Coast Guard Agency‹), national border guards of EU member states and international organizations such as the ICMPD provide technical means for cooperation, deployment forces, supplies, funding and training to non-EU countries.

All border practices that involve acting beyond territorial lines and in coordination with third countries are referred to as instances of »border externalization« (Migration Keywords Collective 2015). The origins of outsourcing border control – and the concurrent tendencies to evade the law and constantly extend geo-juridical boundaries – have their roots in the United States’ interdiction of Haitian refugees in the early 1980s and have since spread, especially among the EU and Australia (Gaibazzi et al. 2016; Zaiotti 2016).

For the EU, border externalization is neither new nor anecdotal. It has characterized the EU’s strategy for containing migration since the 1990s. Based on a restrictive view of human mobility, current policies are inspired by a geographical imaginary of migration flows that is considered as organized in concentric circles and found in an old but influential document: »The EU Strategy Paper on Asylum and Migration« of 1998 (EU Council 1998). These circles encompass the entire globe, and they classify countries as either: 1) desirable destinations and zones of mobility, 2) as countries of transit adjacent to the EU, 3) as countries of transit further away, 4) or as sources of undesirable population flows (see Maps 1-4).

Concentric Circles, Map 1. EU member states/Schengen zone: As the integration of the European Union proceeded, the twenty-odd members of the EU pooled their sovereignty together and created a zone of free movement for goods, capital and people called the Schengen zone. The zone allows you to move, work and study freely in any of its member countries. Considered one of the success stories of the EU, Schengen has come under increasing critique since the so-called financial and refugee crises.

This hierarchical and racialized understanding of rights to mobility constitutes the basis for legitimizing practices of migration control outside EU territorial limits. This approach to mobility is based on designating the members of specific territories and populations as having different entitlements to move. By doing this, focus shifts from border crossings at national limits to a more ›global‹ method of migration control. It becomes necessary to pay attention to the points of origin and transit of those flows: »[a]n effective entry control concept cannot be based simply on controls at the border but must cover every step taken by a third country national from the time he begins his journey to the time he reaches his destination« (EU Council 1998: 13). This vision of migration control, based on the management of migratory journeys, was embraced in the Global Approach to Migration and Mobility framework in 2005 (EU Council 2005; EU Commission 2005) and reinvigorated in 2015, after the Arab Spring uprisings around the Mediterranean.

The conventional understanding of migration control is that each nation-state is in charge of its own borders at territorial lines and ports and manages visas in national embassies abroad. Yet, this approach is considered incomplete within EU migration policy circles, which believe that »efficient migration management« entails going beyond the place and time of the entry point (Interview given to Guardia Civil-Servicio de Fronteras, Madrid, 2013). Thus, it is necessary to establish transnational cooperation in order to track where the migrant is in her/his process of moving towards an assumed destination point in Europe, and to collaborate with the border authorities of other countries to intercept ›potential‹ irregular migrant flows.

Concentric Circles, Map 2. European Neighborhood Partnership: EU candidate countries are potential members of the EU, and must meet Schengen criteria. Transit countries which are adjacent to the Euroepan Union are offered a chance to access some markets in the EU without tariffs, and to participate in the regulatory frameworks through the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP).

Visualizations of Routes?

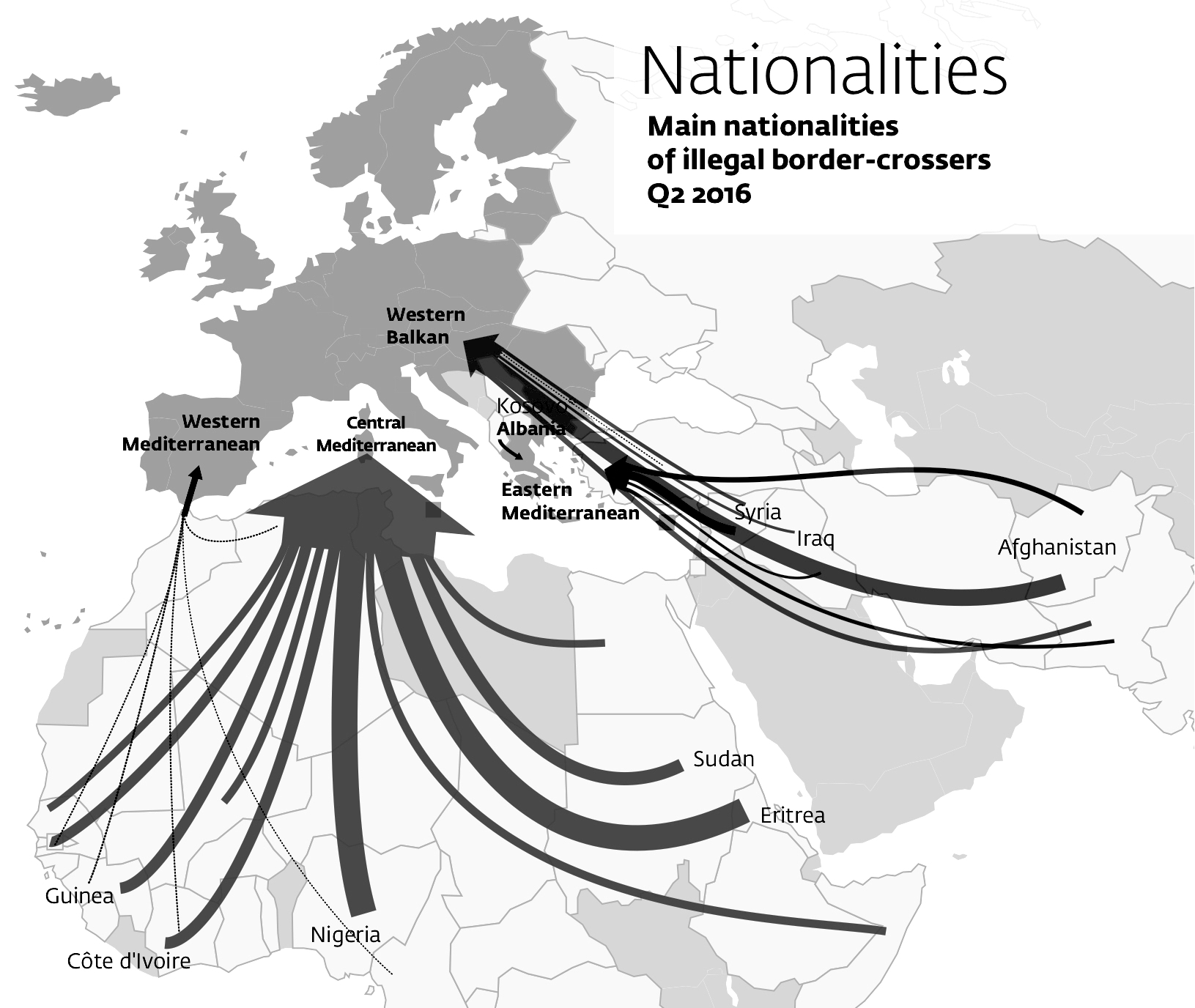

Recent border security objectives attempt to trace and manage the entirety of the journey. This is how the route has become a migration management concept and strategy. Since 2003, the ICMPD has visualized migrant routes, with the intent of managing them. The i-Map, a regularly updated online map, has become a reference point for border management from a distance.4 The map does not trace border walls or empirically represent individual journeys; rather, it focuses on clustering flows into distinct routes that can be managed as shared itineraries with clear points of origin, transit and destination. Initially, the European Commission designated four main routes traversing the African continent: the West African/Atlantic Route, the Western Mediterranean Route, the Central Mediterranean Route, and the East African/Horn of Africa Route.

More recent maps presented on i-Map show how the representation and naming of routes evolve according to perceived transformations of migrant journeys.5 The 2014 version (the most recent non-animated version) is a static representation of migrants’ routes. Professionally designed, the cartographers chose to provide physical geographical details of the regions without emphasizing national borders, nor color-coding national territories as in regular political maps. This way, the web of lines of migrants’ flows receive a prominent role looking as ›empirical‹ as the mountains. While the map conveys a sense of being strongly data driven, we contend that a specific politics of expertise is at work generating a particular vision of human flows. For instance, while there are no arrows on the lines, and thus no apparent directionality, the viewer still gets an overwhelming impression that all those flows are moving towards EUrope.6

Concentric Circles, Map 3. Transit Zone: The transit zone includes many of the ENP countries (which have stronger trade links with the EU), along with other countries, which are seen from the EU as needing to policing migrants that are ‘transiting’ through their countries on the way to the EU. Countries of the third circle are considered to be points of transit for migrants on their way to the first circle. These countries are not offered integration into EU Markets and frameworks.

The i-Map was known in every migration and border agency office in which we conducted interviews. The visual expertise and spatial vocabulary it represents has spread among EU and non-EU border officers, creating a shared way of thinking about migration. The i-Map and its »routes thinking« are now a standard image (in simplified form) in media discussions on the current asylum crisis in Europe. Other migration management agencies, such as FRONTEX (see Map 5) and the International Organization for Migration (IOM), have developed their own routes rendering them inspired by i-Map and its geographical thinking.

The conceptual cartographies that help to imagine and implement ›remote migration control‹ facilitate the coordination of real-time maps typically displayed on border guards’ screens. Migration routes maps complement high-tech surveillance at border zones and are placed into a trans-continental network of border management at times integrating real-time data of suspected border crossers into the more expansive migration routes management architecture.

Concentric Circles, Map 4. Source Countries: The countries of the 4th circle are seen as migration »source« countries, briefly referred to in the 1998 strategy as »the Middle East, China, and black Africa«. The EU approach towards these countries includes border security as in the transit countries but is complimented by programs that encourage people to »stay in their circle«. Countries highlighted on this map are those considered part of the »4th circle« for EU purposes. The stars indicate countries identified as top sources of illegal entries in 2016.

Maps for Imagining and Implementing Remote Migration Control

In visualizing targets as fluctuating routes, these maps do not provide a straightforward empirical representation of the exact numbers of people moving through the routes. The directionality of the routes is not accurate either as Europe is often assumed to be the sole destination without rendering intra-regional migration flows. Such routes maps – widely disseminated among border authorities and migration experts as well as by the media – produce, spread and normalize a particularly restrictive way of thinking about migration control.

Normalizing and even legitimizing the tracking and the management of movement along a migrant route gives rise to controversial border practices. For instance, Spanish border authorities have been deployed in Senegalese territorial waters and coastlands thousands of miles away from the territorial borders of Spain, where they patrol cayucos (fishing boats retooled for possible migration) via satellite technologies, military vessels and aircrafts.

Displacing border control practices to presumed places of origin or transit of migrants has also resulted in EU and non-EU countries conducting additional kinds of sea and land operations. Some are veritable military interventions, such as those that target sites of origin and transit in West Africa: Operation Hera attempts to stop migration along the maritime route between West Africa and the Spanish Canary Islands, and is led by FRONTEX (2006–ongoing).7 Project Seahorse is a transnational police cooperation mission led by Spanish border authorities operating at the same route (2006–ongoing).

Given the ›success‹ of these operations in terms of ›apprehending migrants‹ in the Atlantic, a similar, though further developed, technological infrastructure and modus operandi for surveillance has been applied to the Mediterranean. This effort has at times been known as »Seahorse Mediterranean« and has currently been incorporated into the pan-EU border surveillance network EUROSUR. Other complementary interdiction operations are now underway, such as the markedly military EUNAVFOR Med: Operation Sophia (2015–ongoing).

Outsourcing borders is not a solo enterprise. While the EU and its member states are very invested in these policies, non-EU governments must agree to these efforts and cooperate with them in order for this approach to migration control to work. Most of the time, although EU efforts with third countries are portrayed as creating a »connected global border management community« (FRONTEX 2018) and »capacity building« (ICMPD 2018), collaboration only comes after under certain conditions: development aid, entrance to EU markets or diplomatic support.

Thus, a cross-national institutional architecture is also working in parallel to these paramilitary operations, often through diplomatic processes involving countries whose territories align themself with specific routes. For instance: for the East African Route there is the Khartoum Process (whose main participants include Germany, Italy, Eritrea and Sudan); and for the West African route, the Rabat Process (whose main participants include Spain, France, Morocco, and Senegal).

Counter-Mapping? It is Obvious from the Map

To highlight the expert-driven production of maps on irregular migration and their links to paramilitary border control operations, we describe these various tools and actors as part of a ›mapping migration matrix.‹ We contend that these maps are creating a shared language of expertise and a geographical imaginary of illegality beyond borders. These attempts to normalize controversial practices of managing human mobility are nonetheless contested by migratory movements and their own cartographic productions. These counter-cartographic productions themselves either embody, defend, or push the imagination to embrace the historically established but currently neglected Ius Migrandi or ›Right to migrate.‹8

These ›counter-cartographies‹ can include maps evoking and facilitating freedom of movement made and sent/texted/emailed among refugees and migrants along their journeys or sent to peers or perhaps family members to make their paths smoother. The »It is Obvious from the Map« collection is showcasing a series of maps that speak of the turbulence of migration movements trespassing those sophisticated networks of migration control.

There are drawings that challenge the accuracy of official routes maps and that point to the many alternative journeys going to or around EUrope, many of which are not visible on official maps of routes. The collection mainly focuses on the digital real-time maps created from exchange among migrants in the Mediterranean, who use the technology of mobile phones, scribble over Google maps and share specific tips on Facebook about how to cross certain borders and navigate unknown territories. With their very movement, those labeled by the i-Map as »irregular« or as »asylum seekers« within »mixed migration flows« are embodying a different notion of mobility than the one EUrope wants to regulate, name and classify. One of the phone texts accompanying a personalized Google map indicated how making it to arrive in a new country was »obvious from the map.« This became the title of the collection, which hosts a comprehensive collection of these maps collected by Djordje Balmazovic (Škart collective) in collaboration with non-EU migrants and asylum seekers. These counter-cartographies point to how those who are negated freedom of movement keep moving across borders and visually share tactics about how to do it.

Counter-cartographies of the border regime also include other kinds of mapping initiatives that try to contest the ›big brother‹ feeling conveyed by the official maps, especially the i-Map’s sense of professional accuracy. The local organization of undocumented migrants of Zaragoza, after their initial furious reaction upon discovering the existence of i-Map, decided to organize a series of workshop for collaboratively drawing »Our own map of routes.« The rich reflections coming out of these workshops shifted the usual eyewitness stories coming out of so-called ›illegal‹ and ›risky‹ crossings of the border: instead of a dramatized and often self-blaming narrative, a more empowering self-portrait emerged that was able to pin down the lack of political will on the part of governments to allow people to move. Visually, the obstacles people faced while being in movement are shown by a series of icons incorporated into a map legend. Even if the actual map might be rolled up inside a closet, the final product itself was not central, but rather the reimagining of identities and political demands that emerged through the mapping process.9

Another powerful example of counter-cartographies are the mapping efforts by the Forensic Oceanography project to turn »surveillance against itself« (Heller/Pezzani/Stierl 2017), that is, to map what the border control agents are doing in the Mediterranean Sea, specifically focusing on particular incidents (such as ›left-to-die-boat‹) and visualizing many occurring violations of international law. This »disobedient gaze« (Heller/Pezzani/Stierl 2017) is helpful not only in denouncing the legal and human rights abuses committed by the EU-border regime, but also in flippinging surveillance technologies around to the surveyors, thus turning the question of »who is the illegal one?« upside down.10

Counter-cartographies, within the context of the mapping migration matrix, refer to those graphic and collaborative efforts working for a no-borders ethics. These maps visually show the limits of the seemingly over-powering border regime as well as the obstacles the latter puts in the way of people’s freedom to move, thereby empowering a politics of disobedience towards restrictive and arbitrary border politics.

Literature

Andersson, Ruben (2014): Illegality, Inc.: Clandestine migration and the business of bordering Europe. Oakland.

Bhagat, Alexis / Mogel, Lize (2007): An Atlas of Radical Cartography. Los Angeles.

Casas-Cortes, Maribel / Cobarrubias, Sebastian / Heller, Charles / Pezzani, Lorenzo (2017): Clashing cartographies, migrating maps. In: ACME: Journal of Radical Geography 16 (1). 2–3.

Casas-Cortes, Maribel (2017): Politics of Disobedience: Ensuring Freedom of Movements in a B/Ordered World. In: Spheres: Journal for Digital Cultures 4. 1–6. URL: spheres-journal.org [12.06.2018].

Cobarrubias, Sebastian (forthcoming 2018): Maps of Illegality. The International Center of Migration Policy Development and the Carto-Politics of Migration Management at a Distance. In: Antipode (forthcoming).

De Genova, Nicholas (Ed.) (2018): The Borders of »Europe«: Autonomy of Migration, Tactics of Bordering. Durham.

European Commission (2005): Priority Actions for Responding to the Challenges of Migration: First follow-up to Hampton Court. COM (2005) 621, 30 November. Brussels.

European Union, the Council (1998): Strategy Paper on Immigration and Asylum, 9809/1/98, Rev. 1, CK4 27, ASIM 170.

European Union, the Council (2005): Global Approach to Migration. Priority Actions Focusing on Africa and the Mediterranean. Council doc. 15744/05, 13 December. Brussels.

Feldman, Gregory (2012): The Migration Apparatus: Security, Labor, and Policymaking in the European Union. Stanford.

FRONTEX (2016): FRAN Quarterly. Quarter 2 April–June 2016. Warsaw. URL: frontex.europa.eu [11.06.2018]

FRONTEX (2018): FRONTEX Partners: Non-EU Countries. URL: frontex.europa.eu [16.03.2018].

Gaibazzi, Paolo / Dünnwald, Stephan / Bellagamba, Alice (Eds.) (2016): EurAfrican Borders and Migration Management: Political Cultures, Contested Spaces, and Ordinary Lives. Basingstoke.

Heller, Charles / Pezzani, Lorenzo / Stierl, Maurice (2017): Disobedient Sensing and Border Struggles at the Maritime Frontier of EUrope. In: Spheres: Journal for Digital Cultures 4. 1–15. URL: spheres-journal.org [12.06.2018].

Hess, Sabine (2010): ›We are Facilitating States!‹ An Ethnographic Analysis of the International Centre for Policy Development. In: Geiger, Martin / Pecoud, Antoine (Eds.): The Politics of International Migration Management. London. 96–118.

ICMPD (2018): ICMPD: Our Work – Capacity Building. URL: icmpd.org [16.03.2018].

Migration Keywords Collective (2015): New Keywords: Migration and Borders. In: Cultural Studies 29 (1). 55–87.

Redcat (2017): It is obvious from the map. The Redcat of 25.03.2017. URL: redcat.org [01.01.2018].

What, how & for whom (2018): Signs and Whispers. URL: whw.hr [01.01.2018].

Zaiotti, Ruben (Ed.) (2016): Externalizing Migration Management: Europe, North America and the Spread of »Remote Control« Practices. London/New York.

Thanks to Sohrab Moheddi & Thomas Keenan, curators of the exhibition »It is Obvious from the Map« at the LA based art gallery REDCAT. We value their passionate interest in the EU border regime and their pursuit in making its intricacies accessible to the broader public. Also, we highly appreciate the advice we received from REDCAT’s editor, Jessica Loudis, who carefully reviewed a previous version of this text several times to make it as clear as possible for the exhibit. We also want to thank Ivet Ćurlin, curator and member of What, How & for Whom/WHW collective from Zagreb, who is showcasing these maps at the Nova Gallery. Finally, thanks to cartographer Tim Stallman for working with us on the visualization of the geographic thinking behind some of the key EU documents defining current migration policy. Last but not least, thanks to all of those who keep moving across borders, with or without required papers, for challenging the limited current border system and fully embracing the capacity of humanity to move, exchange and grow in diversity.↩︎

We have further explored this tension among politics and goals underlying maps with the concept of »combat of cartographies« in the article »Clashing Cartographies, Migrating Maps« (2017).↩︎

More maps are included with the online version of this text at movements-journal.org.↩︎

See parts of the initial version of i-Map called »Interactive Map on Migration« at imap-migration.org [01.01.2018].↩︎

For an animation of certain routes see imap-migration.org [01.01.2018].↩︎

For a further engagement with this argument see Sebastian Cobarrubias »Mapping Illegality« in Antipode (forthcoming).↩︎

Operation Hera is coordinated by Frontex, and its aim is to stop migration along the maritime route between West Africa and the Spanish Canary Islands. Effectively, Hera aims to intercept any vessel detected within its area of operation and to divert it back to the port of departure with the authorization and cooperation of Senegalese and Mauritanian authorities. Moreover, individuals who successfully arrive in the Canary Islands are screened and returned to where they came from. The operation has been active since Spanish border authorities requested technical assistance from the EU in 2006, and, according to Frontex, it has been a success. Country flags indicate EU and non-EU governments involved in this operation via transnational patrols and bilateral agreements.↩︎

For a more extensive review of maps denouncing the EU’s border regime see Bhagat/Mogel 2007.↩︎

For a further development on this issue see Casas-Cortes et al. (2017).↩︎

For a further discussion of counter-cartographies as embracing and empowering a politics of border disobedience see Casas-Cortes (2017).↩︎