Abstract This article makes four related arguments regarding the academic field of migration and refugee studies (MARS) in the UK and its relations of knowledge production with UK state agencies. The first, most empirical, argument is that the field’s members harmed their human subjects by providing technical and symbolic assistance to two UK Home Office-managed organisations in controlling migration: the Advisory Panel on Country Information (APCI) and the Migration Advisory Committee (MAC). The second, most theoretical argument is that these MARS-UK state agency relations of production, and the harm that the field’s human subjects experienced as a result, are intelligible as aspects of the neoliberalisation of the capitalist mode of production. The third and fourth arguments that are made in this article are more normative. One is that the similarities between the cases of MARS in the UK and the field in Germany warrant attention both to the latter’s relations of production and to the effects that these might be having (or may have already had) on its human subjects. The other normative argument is that a ›critical‹ MARS is a structural impossibility.

Keywords knowledge production, migration studies, refugee studies, migration control, United Kingdom

There is reason for researchers who prioritize the well-being of people categorized as migrants and refugees to be concerned about recent increases in both the rate of growth of the field of migration and refugee studies (MARS) in Germany and the availability of German state agency funding for MARS research.1 The concern is warranted because these phenomena coincided as well in the UK between 1997 and 2010, when, under ›New‹ Labour governments, MARS academics’ engagement with UK state agencies through knowledge production and exchange harmed the field’s human subjects. In this essay, I describe how this happened and provide an explanation for why it occurred.

I make and support two main arguments. The first is mostly empirical and constitutes the bulk of the essay: MARS academics harmed the field’s human subjects through their participation with two advisory bodies that were managed by the UK Home Office (the Advisory Panel on Country Information [APCI], and the Migration Advisory Committee [MAC]). They did so through knowledge production, thereby providing technical and symbolic assistance to ›New‹ Labour governments in prosecuting their restrictive migration control agendas. My other main argument is more theoretical: both the collaboration of MARS academics and the resulting injury are intelligible as aspects of the neoliberalization of the capitalist mode of production. As the UK state increasingly limited asylum and immigration, it also eroded UK academics’ autonomy, resulting in a situation in which the field of MARS could develop only if it assisted ›New‹ Labour governments in bringing about these new migration controls.

In addition to these two primary, mostly analytical arguments, I make two secondary ones that are more normative and are discussed only at the very beginning and end of this essay. The first, which I have already mentioned, is that the structural similarities between the cases of MARS in the UK and the field in Germany warrant attention, both to the latter’s relations of production and to the effects that these might be having (or may have already had) on its human subjects. The second concerns the ›critical‹ potential of MARS, and it is presented in the last few paragraphs of this essay.

In this article, I provide the evidence that is lacking in the existing scholarship claiming that MARS facilitated migration control by symbolic (legitimation, reification, etc.) and technical (i.e., provision of useful surveillance on targets of control) means. Malkki (1995), Chimni (1998, 2009), De Genova (2002), Black (2003), Peutz (2006), and Zetter (2007) have asserted that the field did so, but they provided very few (or no, in some cases) details on exactly how this happened.2 I take an approach similar to that used by David Mosse (2005) in his study of an academic field that is closely related to MARS – i.e., development studies. Mosse’s monograph

»takes a close look at the relationship between the aspirations of policy and the experience of development within the long chain of organisation that links advisers and decision makers in London with tribal villagers in western India. […] [I]t does not ask whether, but rather how development works« (ibid.: 2; emphasis in original).

Below, I describe – following Mosse – a long chain of organisation that links MARS academics and their human subjects, which includes not only the researchers and the people they study, but also government officials and agencies, members and committees of Parliament, universities (and their research centres), commissioned reports, and money. I trace empirically a network linking the knowledge production with the harm.3

The interpretation that I offer in this essay for the network that I describe is historical materialist; my focus is on how material conditions constrain, but do not necessarily determine, human behaviour over time.4 This approach is, of course, most closely associated with Marx and Engels, who wrote that »circumstances make men just as much as men make circumstances« (Marx/Engels 1974: 59). We all are made and make as part of a mode of production, which Wolf defines as »a specific, historically occurring set of social relations through which labor is deployed to wrest energy from nature by means of tools, skills, organization, and knowledge« (1982: 75; emphasis added). Below, I show how MARS academics’ harm of their human subjects through knowledge production took place in the context of the neoliberal transformation of the capitalist mode of production, which David Harvey (2007) describes as including attacks on workers both at the level of the state and on a global scale.

Before researching MARS academics, I was a MARS academic – albeit briefly. I began my DPhil in 2003 at the University of Oxford studying migrants as a member of its Centre on Migration, Policy, and Society (COMPAS), with its director as my supervisor. Before the end of my first academic term, I had changed the topic of my doctoral thesis; I switched from producing knowledge about migrants to doing so about MARS – the community of which I was a new member.5 My membership, however, was short-lived. By the start of the 2004 academic year, I was no longer part of COMPAS and therefore was out of MARS, as well.6 This article is based mostly on the work that I did between 2003 and 2010 for my doctoral thesis in social and cultural anthropology. I gathered information through methods that included participant observation, interviews, the analysis of official documents, and Freedom of Information Act requests.7

My essay is structured as follows. I begin by providing a brief history of the institutional development of MARS. Then I show how the field’s boom, which began in 1997, was funded by the newly formed Labour government in order to acquire assistance from MARS in increasing restrictions on asylum and immigration. Next, I describe two Home Office-managed advisory panels (the APCI and the MAC), the ways that MARS academics participated in these organizations, and what the resulting harmful outcomes were for their human subjects. In the penultimate section, I explain how the complicity of MARS academics developed through the neoliberal capitalist transformation both of academic labour in the UK and of the mobility of labour at the global scale. In my conclusion, I discuss the similarities between the case of MARS in the UK and that of the field in Germany, and I end by offering some personal reflections on my findings.

MARS in the UK

I identify as MARS academics those people who are students, researchers, or faculty at universities and who also do one or more of the following: 1) produce knowledge about people objectified as migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers, or about the processes in which they are the primary actors, such as migration, transnationalism, diaspora, and integration; 2) belong to research centres that specialize in this kind of production; 3) enrol in or teach on postgraduate courses based on this knowledge; 4) edit journals dedicated to these products; and 5) belong to one of a limited number of related professional associations.

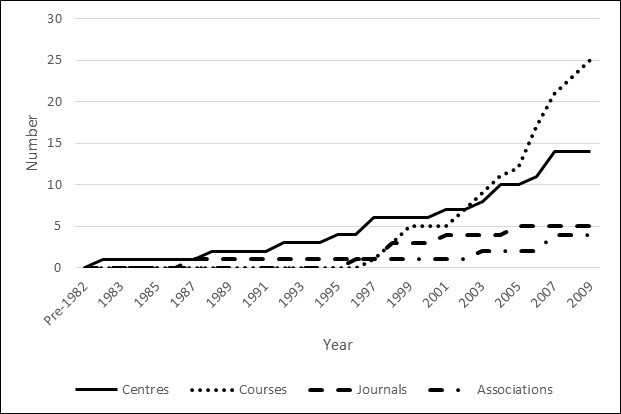

MARS has emerged in the UK recently vis-à-vis other multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary academic fields of study, such as development studies.8 Its first research centre – the Refugee Studies Programme (RSP) at the University of Oxford, which was later renamed the Refugee Studies Centre (RSC) – was established in 1982. Many subsequent additions, such as the Centre on Migration, Policy and Society (COMPAS) at the University of Oxford in 2003, made migration an explicit focus of their research. MARS’s first journal – the Journal of Refugee Studies – was begun at the RSP in 1986. One of several that followed was the Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies (in 1998), which has been edited by MARS academics at the University of Sussex Centre for Migration Research (SCMR). The International Association for the Study of Forced Migration – the field’s first professional association – had its inaugural meeting in 1996.

The field’s first degree course – the MA in Refugee Studies at the University of East London (UEL) – began in 1997. Later examples include master’s and doctoral courses in Migration Studies (at the SCMR and COMPAS); Migration, Mental Health, and Social Care (at Kent); and Migration and Transnationalism (at Nottingham). In total, by the autumn of 2008, 16 centres had been established at 11 universities, five journals had been founded at three universities, four professional associations had formed, and 23 postgraduate courses had been offered at 11 universities. This institutional development is depicted below in Figure 1.9

As seen in Figure 1, above, MARS experienced a boom beginning in 1997. In the 14 years preceding this growth spurt, the field had established only four centres, one journal, one association, and zero courses. In the 12 years between 1997 and 2009, however, the field grew by 10 centres, four journals, three associations, and 25 courses. As I will demonstrate in the following section, this dramatic 1997-and-beyond expansion was the result of intensive and focused capital investment in the field by the state agencies of ›New‹ Labour governments.

›New‹ Labour’s Funding and Expectations of MARS

The rapid post-1996 growth of MARS was made possible primarily by funding from UK state agencies. The injections into the field by these organizations of research funding exceeding one million pounds are listed in Table 1, below.

| Year | State agency10 | Recipient(s) | Amount (£) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1997 | ESRC | Transnational Communities Programme (Oxford) | 3.8m |

| 2000 | HO IRSS | Various | 1.2m11 |

| 2003 | ESRC | Centre on Migration, Policy and Society (Oxford) | 3.8m |

| DFID | Development Research Centre on Migration, Globalisation and Poverty (Sussex) | 2.5m | |

| 2005 | AHRC | Diasporas, Migration and Identities Programme (Leeds) | 5.5m |

| 2006 | DFID | Refugee Studies Centre (Oxford) | 2.5m |

| 2008 | ESRC | Centre on Migration, Policy and Society (Oxford) | 4.8m |

| Total: | 24.1m |

These investments by state agencies directed by Labour governments were of vital importance to the MARS centres they funded. The centres relied heavily on external – i.e., grant and contract research – funding, the bulk of which they acquired from UK state agencies and other governmental sources, as seen in the examples in Table 2, below.12

| Percentage of Total External Funding from | ||

|---|---|---|

| MARS Centre (Years) | UK State Agencies | All Governmental Sources (including UK State Agencies) |

| COMPAS (2005/06–2006/07) | 85 | 90 |

| RRC13 (2003/04–07/08) | 70 | 77 |

| SCMR (2003/04–07/08) | 56 | 84 |

That COMPAS, a centre with the word »Policy« in its name, acquired nearly all of its external grant income from UK state agencies and other governmental sources might be less surprising to the reader, perhaps, than the finding that the University of East London’s Refugee Research Centre, an institution perceived by the field’s members as being particularly pro-migrant and pro-refugee, and which a MARS master’s student described to me in 2008 as having »a lefty bent«, received such a substantial portion of this type of income from such agencies. In other words, even the MARS centre that had a reputation for having the least governmental politics in the field acquired around three-quarters of its external grant income from governmental sources.

Labour government state agencies channelled large grants to the directors of MARS centres whom they knew through prior interactions. All of the directors of the UK state agency-funded academic centres listed in Table 1 had cooperated in one way or another with the Labour Party during either its opposition (i.e., pre-1997) or its government phase prior to the awarding of these funds. This collaboration ranged from doing contract research for the Home Office, to being a member of one of the Home Office’s advisory panels, to standing for election as a Labour Party candidate.14

Once the Labour Party came to power in the 1997 general election, its governments proceeded to generate new and more restrictive primary legislation in the field of migration at double the rate of the previous Conservative governments (eight in 13 years vs. four in 13 years), as seen below in Table 3.15

| Party in Government (Years) | Legislation |

|---|---|

| Conservative (1984–1996) |

|

| Labour (1997–2009) |

|

›Evidence-based policy‹ was implicit in the Labour Party’s rhetoric during its 1997 general election campaign,16 and it was also a slogan that the party used explicitly once in government to describe (and legitimize) its policy making process.17 The Labour government turned to the fledgling academic field of MARS (and especially the directors of the field’s research centres) for the ›evidence‹ – i.e., the technical and symbolic assistance that I describe below – that it needed for its increasingly restrictive ›evidence-based‹ asylum and immigration policies. In the following section, I describe how MARS academics answered the call through their knowledge production and exchange activities with the Home Office’s Advisory Panel on Country Information (APCI) and Migration Advisory Committee (MAC).

The Harmful Effects of MARS Academics’ Cooperation with the APCI and the MAC

In this section, I show how MARS academics harmed their human subjects through relations of knowledge production and exchange with the Home Office-managed APCI and MAC. For each of these advisory bodies, beginning with the APCI, I describe the political context of its creation and activities, the involvement by MARS academics, the technical and symbolic assistance that this provided,18 and finally, the harm that befell the field’s human subjects as a result.19

The APCI

The creation of the APCI was mandated by the 2002 Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act, and represents a concession by the Labour government to the members of parliament (MPs) and pro-refugee NGOs that opposed the inclusion in the Act of its ›Safe Country‹ (SCO) and ›Non-Suspensive Appeals‹ (NSA) provisions. These enabled the Home Office to ›certify‹ asylum claims that it rejected as being ›clearly unfounded‹, and to create and add to (with parliamentary approval) a list of countries that were ›safe‹ to be returned to by people whose claims had been refused. Additionally, the Act prohibited the appeal of asylum decisions from within the UK by people whose claims had been ›certified‹ as being ›clearly unfounded‹ and who were citizens of or were entitled to reside in states that were included on this list of ›safe‹ countries. Such people’s presence in the UK was criminalized immediately, they were made eligible for deportation, and they could file an appeal of the rejection of their asylum claims only from outside the UK. Their appeals were ›non-suspensive‹ in the sense that their deportation would not be suspended while they appealed, as it otherwise would have been.

The concerns of many of the opponents of the SCO and NSA provisions were assuaged by the creation of the APCI, because it was charged with assisting the Home Office in improving the quality of the Country Reports (CRs) that the Labour government had pledged to use when judging if a country was ›safe‹ enough to be added to the SCO/NSA list, which critics called the ›White List‹. CRs – descriptions of the human rights and security situations in particular states – were already in use by the Home Office for evaluating asylum claims and in the asylum appeals process, and they had been roundly criticized for years by pro-asylum NGOs for inaccuracies and omissions (Good 2007: 214–215; Huber/Pettitt/Williams 2010: 24–25).

The Labour government expected the APCI to help it to overcome the remaining opposition to its new additions to the ›White List‹ – resistance that is clear in the following statement made by a Liberal Democrat MP during parliamentary debate in 2003: »We are opposed in principle to the white list, and we shall divide the Committee on the matter, as we will the House [of Commons]. […] The Government have been warned« (Hansard 2003). The Labour government’s expectation of the legitimation of its SCO/NSA decisions by the APCI is clear in the following statement from the minutes of the panel’s first meeting:

»The Home Office commented that there had been some opposition to the addition of some countries to the NSA list. If the country information in relation to such countries [e.g., Country Reports] had been considered by the Panel, this may provide some reassurance that the decision to designate a particular country had been made on a sound basis« (APCI 2003: §3.8).20

The APCI first met in September of 2003 and held its last meeting (its thirteenth) in October of 2008.21 MARS academics participated as the panel’s unremunerated members (APCI 2008: §6.3; APCI n.d.) and as compensated commissioned researchers. By its tenth (March 2007) meeting, the panel had had 10 MARS academics as members. A chronology of the membership of these individuals during this period is shown in Table 4, below.

| APCI meeting | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Member | University | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Prof. Stephen Castles (C) | Oxford | M | M | M | M | M | |||||

| Prof. Vaughan Robinson | Wales (Swansea) | M | m | m | m | m | |||||

| Prof. Richard Black | Sussex | M | M | m | m | m | |||||

| Prof. Gil Loescher | Oxford | U | M | m | M | M | m | M | m | M | |

| Dr. Khalid Koser (C) | UCL22 | M | M | m | m | M | M | N | N | N | |

| Prof. Lord Bhiku Parekh | LSE,23 Westminster | m | M | M | m | m | |||||

| Dr. Alan Ingram | UCL | M | M | M | M | ||||||

| Dr. Chris McDowell | City | M | M | M | |||||||

| Prof. Roger Zetter | Oxford | M | M | M | |||||||

| Dr. Laura Hammond | Reading | M | M | ||||||||

Key: M: Member and Attended; m: Member, but Did Not Attend; U: Member, but University Undetermined; N: Member, but Not Academic; C: Chair

These 10 academics were based at six different universities, with only one academic being based at more than one university during the period of membership. Half were the directors of MARS centres at the time they joined the panel. Two (Professors Castles and Zetter) directed Oxford’s RSC. The other three (Dr. McDowell and Professors Robinson and Black) did so for City University’s Information Centre on Asylum and Refugees; the University of Wales, Swansea’s Migration Research Unit; and the SCMR, respectively.

MARS academic panel members provided technical assistance to the Home Office and thereby harmed their human subjects by aiding the Home Office in its production of the CRs that were used in the asylum determination and appeals processes. APCI-commissioned researchers edited these CRs – sometimes multiple drafts of the same report – for accuracy, comprehensiveness, representativeness, and structure. APCI panel members identified the researchers to be awarded these contracts. Between its first and its seventh (March 2006) meetings, MARS academic panel members channelled 12 research contracts, worth slightly under £5,000 each, for CR evaluations, to themselves (Dr. Koser and Prof. Black), their MARS centre or university colleagues, and academics at other UK universities.24

Many of the commissioned analyses – especially the early ones – criticized the CRs. For example, Dr. Koser and Ms. Ceri Oeppen, a MARS graduate student at the SCMR,25 found »many examples of a lack of accuracy, representativeness and comprehensiveness« in the April 2004 CR on Afghanistan (APCI 2004a: 5). Their »Overall Assessment« that they gave several months later of the Home Office’s revised CR was much more positive:

»The October 2004 report is a significant improvement on that of April 2004. Some problems have persisted, but on the whole even these would appear to have less serious implications than previously. We have fewer reservations over the value of the current report as evidence in assessing asylum claims from Afghanistan« (APCI 2005: 6).

By the panel’s seventh (March 2006) meeting, both commissioned researchers and panel members were giving the CRs very positive evaluations. For example, the minutes of this meeting included the following statement: »The Chair agreed that with the consistently good standard of COI Reports [i.e., CRs] now being produced, the issue of ›diminishing returns‹ would need to be considered by the Panel« (APCI 2006: §3.12). In other words, he judged that the panel had improved the quality of the CRs so much that the very minor problems that the CRs had at that point no longer warranted the large amount of effort that was required by the APCI to do its work.

The Home Office used the CRs, which MARS academics had helped to produce, to harm the field’s human subjects by rejecting asylum claims and challenging asylum appeals. Home Office officials compared the statements made by asylum applicants with the information contained in CRs, and they rejected claims when the testimony did not match with the documents (Huber/Pettitt/Williams 2010: 24; Morgan et al. 2003). Furthermore, Home Office presenting officers used CRs to challenge the testimony of people who were appealing the rejection of their asylum claims before the Asylum and Immigration Tribunal (ibid.). The reliance on and trust in the CRs by the tribunal’s judges has been confirmed by both an ethnographer of the asylum process (Good 2007: 215) and the tribunal’s vice president (APCI 2004b: §3.5).

MARS academics participating with the APCI provided the Home Office with not only technical assistance, but also that which was symbolic. By giving positive evaluations of CRs, they helped Labour governments to overcome parliamentary opposition to their policies that were harmful to the field’s human subjects. The positive assessments of CRs that appeared in panel-commissioned analyses and those that were given verbally during panel meetings were used by government representatives while arguing for adding countries to the ›White List‹ during parliamentary debate. An illuminative example is that of India.

The APCI met on 7 December 2004 (its fourth meeting) to discuss the evaluation that it had commissioned of the India CR. At the end of the presentation and discussion of the commissioned analysis, the panel’s chair (Prof. Castles) is minuted as stating that the report was »basically sound« (APCI 2004c: §3.18) and that »the view of the meeting was that, despite some problems, the Country Report was generally a fair reflection of the country situation and source material« (ibid.: §3.21).

Two months later, on 8 February 2005, the government’s immigration minister made its case in a House of Commons committee for adding India to the SCO/NSA list. In his response to the second question from an opposition (Liberal Democrat) MP during the debate, the minister told the committee that the government had made a commitment to ask the »independent« (Hansard 2005) APCI to evaluate the CRs that it used when deciding whether or not to add a country to the list, and that it had done so with India (ibid.). He stated – echoing the APCI’s chair – that »the panel had a few concerns about the way in which the country report was structured, but it concluded that it was generally a fair reflection of the position in India« (ibid.). Aside from issues of »presentation«, he continued, »the independent advisory panel found that our country information on India was essentially sound« (ibid.). Moments later, the committee agreed to the addition of India to the SCO/NSA list.

The order adding India to the list took effect on 14 February 2005. By 30 September 2005, the asylum claims of 390 people who were identified as being Indian citizens (out of 470 people identified as such who had been refused) were ›certified‹ by the Home Office as being ›clearly unfounded‹ (UK Home Office 2005: 4, 13). Their presence in the UK was consequently criminalized, and they were made bureaucratically eligible for arrest, imprisonment, and deportation. Having shown how MARS academics harmed their human subjects through their participation with the APCI, I next proceed to relate how they did so, as well, by working with the Migration Advisory Committee (MAC).

The MAC

The political context of the founding of the MAC differed significantly from that of the APCI. The Labour government – especially its Home Office – was under extreme pressure in the spring of 2006 following election losses, a scandal over the release of ›foreign nationals‹ from UK prisons, and a general increase in anti-immigrant sentiment. It responded by appointing a new home secretary, John Reid, to head the Home Office, and by introducing a new ›points-based immigration system‹ that would discriminate against so-called ›low-skilled workers‹.26 Secretary Reid stated to a parliamentary committee in December of 2006 that, alongside the introduction of this new system, he »personally would like to see an independent Migration Advisory Committee, a committee independent of government, which indicates to government publicly advice on the most beneficial level of immigration« (Select Committee on Home Affairs 2006). He got his wish: the Home Office-managed MAC first met a year later in December of 2007 and had met 22 times by January of 2010.

MARS academics harmed their human subjects via their participation in the MAC by providing the Home Office with technical assistance in restricting immigration. This assistance took the form of research that analysed the participation of migrant workers in the UK labour market. MARS academics participated in the MAC in two ways; several were its commissioned researchers, and one was a member of the committee. The MAC commissioned seven reports on labour shortages and immigration from 13 authors, one of whom was Dr. Andrew Geddes, a MARS academic at the University of Sheffield. The committee also commissioned a study by MAC member Dr. Martin Ruhs and his COMPAS colleague, Dr. Bridget Anderson, which synthesized the findings of these reports. Two additional members of COMPAS – researcher Dr. Rutvica Andrijasevic and a graduate student27 – assisted Dr. Ruhs and Dr. Anderson on the project (Geddes 2008: 3–4), which the centre received £37,250 to carry out (Economic and Social Research Council 2008).

Dr. Anderson and Dr. Ruhs described their commissioned study in the following way: »This paper […] provide[s] an independent analysis and assessment of the nature and micro-level determinants of staff shortages and the employment of migrants in key sectors and occupations of the UK economy« (Anderson/Ruhs 2008: 3). The information contained within the other MAC-commissioned reports was indeed included by Dr. Anderson and Dr. Ruhs in their synthesis. For example, they cited Dr. Geddes’ paper for the finding that »nearly 90 percent of agency workers employed in second stage food processing businesses were migrants« (ibid.: 18). They concluded the review’s executive summary section as follows: »[A]n incremental approach that encourages employers to pursue alternatives to immigration [i.e., migrant labour] may be more successful than a ›big-bang‹ approach that suddenly and significantly reduces access to migrants« (ibid.: 8). The overview paper was one of several others that were brought together by MARS academic Dr. Ruhs and his MAC colleagues in producing another report: »Skilled, shortage, sensible« (UK Border Agency 2008).28 This study identified the ›skilled‹ occupations for which its authors claimed that there was a labour shortage in the UK that could »sensibly be filled by immigration from outside the European Economic Area« (ibid.: 11), and those that supposedly could not.

On 9 September 2008 the Home Office publicized the presentation of the MAC’s »Skilled, shortage, sensible« report in a press release that quoted the border and immigration minister, Liam Byrne, as follows:

»Our new Australian-style points system is flexible to meet the needs of British business while ensuring that only those we want and no more can come here to work. This tough new shortage occupation list supports that. […] We are grateful for the work the Migration Advisory Committee has carried out. We will be pressure testing their conclusions before publishing our final list in October« (UK Home Office 2008a).

The Home Office announced the new shortage occupation list on 11 November 2008, stating in its press release: »Today’s list is tighter than ever before […]. The number of positions available to migrants has been reduced from one million to just under 800,000« (UK Home Office 2008b). As a result, as the Daily Telegraph then reported, »thousands of foreign GPs, midwives and care workers will continue to find it far harder to come after such jobs were excluded from the list« (Whitehead 2008).

MARS academic Dr. Ruhs of COMPAS provided symbolic assistance, as well, to the Labour government through his activities with the MAC. He was listed as a co-author on a number of MAC reports in addition to »Skilled, shortage, sensible«. In one, Dr. Ruhs and his colleagues studied the potential economic impact of removing the UK’s employment restrictions on people with Bulgarian and Romanian citizenship, concluding: »We do not recommend fully removing UK labour market restrictions on employment of A2 [i.e., Bulgarian and Romanian] nationals« (Migration Advisory Committee 2008: 8–9, bold in original). In a second report, Dr. Ruhs and his MAC colleagues addressed the potential labour market impacts of the abolition of the Worker Registration Scheme (WRS) – a UK policy that required people with citizenship of one of the eight new accession states of the European Union (A8) to apply (along with a fee) to register their employment when working for a particular employer in the UK for more than a month (Migration Advisory Committee 2009). The foreword of this report included the following: »[W]e recommend maintaining the WRS […] because, if [it] were […] ended, the labour inflow from the A8 countries would probably be a little larger than otherwise« (ibid.: 4).

The Home Office used these recommendations to overcome parliamentary opposition to its restrictive policies targeting migrant workers from the EU accession countries. In May of 2009, the Home Office minister for borders and immigration invoked the authority of the MAC and its findings when seeking (and ultimately receiving) approval from the House of Commons European Committee for keeping both the work permit restrictions on prospective migrants in the A2 countries and the WRS for migrant workers from the A8 states (Hansard 2009). The Minister told the Committee in his opening statement that the Government had »sought expert advice« (ibid.) from the MAC on whether or not to continue these restrictions, and the MAC had recommended that both be maintained (ibid.).

The pre-emptive nature of the Home Office minister’s inclusion of MAC findings and recommendations was demonstrated by statements that were made during the subsequent debate on the matter by two MPs – one Conservative and one Liberal Democrat. Both argued against the maintenance of restrictions on the grounds that these were »an interference to the way in which businesses go about their work« and a violation of »the principle of extending freedom of movement«, respectively (ibid.). Despite this opposition from two of its members, the European Committee agreed to endorse the Home Office’s restrictive policy.

Table 5, below, summarizes the evidence that I have presented in this section on the ways that MARS academics harmed their human subjects through their cooperation with the APCI and the MAC.

| Type of Assistance Provided to the Home Office | Specific Activities of MARS Academics | Harmful Home Office Practices Assisted |

|---|---|---|

| Technical | ||

| ACPI | Co-produce (edit) country reports | Reject asylum applications and challenge appeals |

| MAC | Describe the participation of migrant workers in the UK labour market | Select occupations to restrict for work visas |

| Symbolic | ||

| ACPI | Give positive evaluations of Country Reports | Acquire parliamentary consent for adding countries to the SCO/NSA list |

| MAC | Recommend maintaining labour market restrictions on migrant workers from the A2 and A8 countries | Acquire parliamentary consent for maintaining labour market restrictions on migrant workers from the A2 and A8 countries |

Having described the ways that MARS academics harmed their human subjects through their knowledge production and exchange practices with the APCI and the MAC, I now proceed with an historical materialist interpretation of these phenomena.

MARS Academics’ Knowledge Practices and Harming of their Human Subjects as Aspects of Neoliberalization

Both the relations of production and exchange of MARS, and the resulting harm that befell the field’s human subjects that I described above are intelligible as aspects of the neoliberalization of the capitalist mode of production. Harvey (2007) discusses this reorganization of global capitalism that has occurred during the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s. »The general attack against labour« during this period, he observes, »has been two-pronged« (ibid: 168). At the scale of the state, there has been the erosion of workers’ autonomy. At the global scale, there has been the restriction of workers’ mobility.

The Erosion of Academic Workers’ Autonomy

The position of academics at UK universities has been weakened significantly by UK state agency actions since the coming to power of the Conservatives in 1979. According to the anthropologist of education, David Mills (2008), the »political economy of the social sciences in the UK has changed profoundly since the 1980s« (ibid.: 180). Per-student funding has been cut, the security of tenure has been abolished, and audit technologies (such as the Research Assessment Exercise/Research Excellence Framework) have been introduced (Tapper 2007; Shore/Wright 2000).

An effect of these actions is that UK-based academics have been increasingly required to generate revenue through entrepreneurial activity – especially via contract research (Slaughter and Leslie 1997; Etzkowitz 2001; Lucas 2006; Allen/Imrie 2010). Research activity by academics has been largely commodified. Imrie has characterised this commercialization of academic activity as being a »scramble for cash« (Imrie 2010: 38). That MARS academics were obliged to participate in this scramble, as well, is clear in the published statements of its high-ranking figures. For example, APCI chair Castles observed that when studying forced migration from a sociological perspective, »researchers often have no choice but to seek their funding from policy bodies (like the Home Office or the European Commission)« (Castles 2003: 26).29

The financial dependency that I described above of MARS on governmental agencies has strongly conditioned the behaviour of its members. Again, the field’s high-ranking members have stated publicly that this has been the case. For instance, a former director of Oxford’s Refugee Study Centre (RSC), David Turton, wrote the following of the MARS sub-field of Refugee Studies: »Its concern to be ›relevant‹ (and, it must be admitted, its need for funding) led it to adopt policy related categories and concerns in defining its subject matter and setting its research agenda« (Turton 2003: 1).30 Several years before becoming the director of the RSC and joining the APCI, Prof. Zetter indicated in a publication that MARS academics’ financial dependency obliged them not only to make changes in their research agenda, methods, and findings,31 but also to engage in what anthropologists call gift exchange (Mauss 1990) with their governmental patrons.

The paper that Prof. Zetter presented at the Home Office-organized ›Bridging the Information Gaps‹ conference in London in 2001 included a statement on how he saw his being asked by the Home Office to describe and evaluate their contract research relationship publicly at the event:

»I have been passed a slightly poisoned chalice. If I am too critical of the relationship we have had with the Home Office, then we may well exclude ourselves from any future tendering!« (UK Home Office 2001: 21)

Commodity exchange – i.e., money for research (Prof. Zetter’s »future tendering«) – depended on gift exchange – i.e., an unremunerated, public, and positive evaluation of his commodity exchange experience. I posit that the unremunerated participation of MARS academics with the APCI and MAC was also a gift.

This interaction bears a strong resemblance to the kula system of the people of the Trobriand Islands famously analysed by Malinowski (1932) and re-interpreted by Mauss (1990) in classics of anthropology and sociology, respectively, in the 1920s. Both the kula and the exchange that I described above involved high-status individuals (recall that half of the MARS academic members of the APCI were centre directors; another had already been made a peer in the UK Parliament House of Lords). Both were »trade […] of a noble kind« (ibid.: 28). Furthermore, in both cases, the ostensibly voluntary was actually obligatory (ibid.: 7); in Malinowski’s terms, »Noblesse oblige« (Malinowski 1932: 97).32 The multimillion pound grants that Labour government agencies made to MARS centre directors who were already known to and trusted by Home Office officials were counter-gifts in their developing reciprocal relationship.33

Additionally, the MARS academic-Home Office kula-like relationship »form[ed] the framework for a whole series of other exchanges« (Mauss 1990: 27), such as the vital commodity exchange of contract research with UK state agencies, which is akin to the Trobriand gimwali – i.e., »commonplace exchanges« (ibid.).34 In sum, MARS academics’ structural need for funding influenced their decisions to participate in the knowledge production and exchange activities of the APCI and MAC; this interaction provided them with relatively small, short-term research contracts and the opportunities both to distribute these to their institutional colleagues and to gain the favour of state agencies with the potential to allot future contracts and grants of varying sizes and durations.

The Restriction of Mobility

According to Harvey, the »second prong« (Harvey 2007: 168) of the attack on labour under the neoliberal reorganization of capitalism has involved the restriction of workers’ mobility (ibid.: 168–169).35 European colonialism had extended the capitalist mode of production – and its »characteristic capital-labor relationship« (Wolf 1982: 383) – into areas previously dominated by tributary and kin-based modes (ibid.). In the neoliberal capitalist present, the »main axis of geographical differentiation at the [global] scale« is, according to Neil Smith, the »differential determination of the value of labor power, and the geographical pattern of wages thus effected« (Smith 2008: 187).

State migration controls have functioned within the post-colonial and neoliberal capitalist modes of production to help to reproduce global inequalities in labour power, and consequentially, wage differentials. By deterring and preventing people in low-wage areas from using relatively inexpensive means of transportation to access areas with higher wages, state migration controls have helped to produce the former as »areas of redundant labor supply and lower labor costs« (Wolf 1982: 382). People who have been ›kept in their place‹36 have supplied capitalists with reserves of low-cost labour for both a) importation, and b) work with exported capital.37

The MARS knowledge production and exchange practices through the APCI and the MAC that I have described can be understood as the actions of members of the managerial class, whose role is to help the capitalist state to »maintain and further the strategic relationships governing the […] deployment of social labor« (Wolf 1982: 308). »Like workers, they are exploited by capitalists (who make a profit from managerial work), yet like capitalists themselves they dominate and control workers« (Scott/Marshall 2009). In sum – and in keeping with Harvey’s metaphor – the knowledge practices of MARS academics in the UK and the injury that these activities caused their human subjects can be conceptualized as an area of human activity that had been skewered by both prongs in capital’s neoliberal feast on labour.

Evidence that the carving fork is still firmly stuck in and the cutting goes on is the continued activity and membership characteristics of the APCI and MAC in the present. Despite the change from a Labour to a Conservative government in 2010, both panels have remained active and have included MARS academics as participants.38 MARS academics from Oxford, Sussex, and UCL are still members of the APCI (now called the Independent Advisory Group on Country Information [IAGCI]),39 and Oxford’s COMPAS still has its representative on the MAC.40 This trade between MARS and the UK Home Office also continues to be of a noble kind. Current APCI/IAGCI members include the co-chair of UCL’s Migration Research Unit and the director of research and knowledge exchange (!) at the University of Sussex.41 Additionally, the current chair of the MAC was formerly the head of the Economics Department at London School of Economics, and one of the committee’s members directs the Migration Observatory at Oxford’s COMPAS.42 ›New‹ Labour may be a thing of the past, but the neoliberalization of capitalism and its associated relations of production among the UK Home Office, MARS academics, and their human subjects that were established during the party’s time in government persist.

Conclusion

In this essay, I demonstrated that it was through their knowledge production and exchange with the UK state agencies of the APCI and the MAC that MARS academics in the UK facilitated migration control and thereby harmed the people that they studied. I also explained these phenomena as emerging in the context of neoliberal capitalism’s attacks on labour via the erosion of the autonomy of academics in the UK and the increasing restriction of the international movement of workers.

I called this essay a cautionary tale in its subtitle because of the similarities that exist between the cases of MARS in the UK and in Germany in two main areas. One is that of the coincidence of increases in state agency funding for MARS and the rate of growth of the field. The UK state provided at least £24m over a 10-year period, and the German state appears to be funding MARS at a comparable rate, with millions of euros for the field in 2016 from the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung, and funding from the Deutsche Forschungsgesellschaft in 2015 for the Grundlagen der Flüchtlingsforschung at the Institute for Migration Research and Intercultural Studies (IMIS), University of Osnabrück.43 The success of journals such as movements (2014) and the Zeitschrift für Flüchtlingsforschung (2017) mirrors that of MARS journals in the UK and is a testament to the field’s growth in Germany.

A second area of similarity between the British and German cases of MARS is that of the neoliberalization of capitalism in general and in academia in particular. As it was in the UK, the autonomy of academic workers in Germany has been diminished through an increased dependency on grant money and pressure to acquire this external funding – referred to as Drittmittel in Germany – through programmes such as the Exzellenzinitiative.44 Additionally, the increasingly restrictive immigration and asylum policies of the UK’s ›New‹ Labour governments described above are paralleled by those of the German state since 2015.45 In particular, the recent addition of Balkan countries to its list of ›safe‹ countries by the German state mirrors the UK’s MARS academic-aided expansion of its ›White List‹.

These similarities merit the careful investigation of the relations of production of MARS academics in Germany and the effects that these have had, are having, or could have in the future on the field’s human subjects. The prevention of damaging outcomes like those that I described above for people categorized as migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers should be the priority for researchers – especially those who have been making a living by producing knowledge about them.

Personal Reflections46

I used to make a living by producing knowledge about people who were in structural positions similar to those of the human subjects of MARS. It was only after I had begun my degree at Oxford in 2003 that I did an honest accounting of my own relations of production. I had just received a fellowship worth nearly £10,000 from the university on the basis of my prior academic work, which featured both a master’s thesis and a publication (Hatton 2002) in which I wrote about low-income, indigenous people in Nicaragua.47 I realized whilst at Oxford that I had exploited these people that I had studied (and many of whom I had befriended). We had produced a commodity – i.e., knowledge – together, but my share of the profit after I exchanged it on the academic market was much greater than was theirs. While my economic opportunities had become nearly limitless with the prospect of an Oxford degree, they continued to struggle for the basic necessities of life. I am certain that MARS academics who do a similar accounting will find the same kind of imbalance in their relation to the people they study.

To those who might claim that a ›critical‹ MARS is possible, I say: Please don’t fool yourselves. A field that exploits its human subjects and produces knowledge that can be used as surveillance on them is ›critical‹ only in the liberal – not the revolutionary – sense of the word.48 The production of knowledge about ›migrants‹, ›refugees‹, and ›asylum seekers‹ by the UK-based MARS academics considered to be the most ›critical‹ about restrictive policies, such as Liza Schuster (2005), Bridget Anderson (Anderson/Ruhs/Rogaly 2012), and Matthew Gibney (2000), demonstrates MARS’s deep and essential material reliance on the exploitation of its human subjects. Similarly, the purportedly ›kritische‹ Grenzregimeforschung of a MARS academic research network in Germany, Kritnet, stands not alone, but rather is tied up with Migrationsforschung that is also – and ostensibly – ›kritisch‹.49

Whose side are you on? If it is that of labour, and you feel that you must produce research, then avoid or abandon MARS, and provide its human subjects with useful counter-surveillance on the actors, discourses, and structures that threaten them. If, however, you are on the side of capital, then MARS is for you.

Literature

Allen, Chris / Imrie, Rob (2010): The Knowledge Business. A Critical Introduction. In: Allen, Chris / Imrie, Rob (Eds.): The Knowledge Business. The Commodification of Urban and Housing Research. Burlington. 1–19.

Anderson, Bridget / Ruhs, Martin (2008): A need for migrant labour? The micro-level determinants of staff shortages and implications for a skills based immigration policy. URL: webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk [08.06.2018].

Anderson, Bridget / Ruhs, Martin / Rogaly, Ben (2012): Chasing Ghosts. Researching Illegality in Migrant Labour Markets. In: Vargas-Silva, Carlos (Ed.): Handbook of Research Methods in Migration. Cheltenham. 396–410.

APCI (2003): APCI.1.M. Minutes of 1st Meeting held on 2 September 2003 at 2.30pm at the Home Office, Room 1028, Queen Anne’s Gate. URL: webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk [12.03.2018].

APCI (2004a): APCI.3.3a. Commentary on April 2004 Country Information and Policy Unit (CIPU) Report on Afghanistan. URL: webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk [12.03.2018].

APCI (2004b): APCI.2.M. Minutes of 2nd Meeting held on 2 March 2004 at 2.30pm at the Home Office, Room 1028, Queen Anne’s Gate. URL: webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk [12.03.2018].

APCI (2004c): APCI.E1.M. Minutes of Extraordinary Meeting held at 2pm on 7 December 2004 at London Hilton, 22 Park Lane, London W1. URL: webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk [12.03.2018].

APCI (2005): APCI.4.1. Commentary on the October 2004 Country Information and Policy Unit (CIPU) Report on Afghanistan. URL: webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk [12.03.2018].

APCI (2006): APCI.6.M. Minutes of 6th Meeting held on 8 March 2006 at Chatham House, 10 St James’s Square, London SW1 Y4L. URL: webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk [12.03.2018].

APCI (2008): APCI.11.M. Minutes of 11th Meeting held on 7 October 2008 at Chatham House, 10 St James’s Square, London SW1Y 4L. URL: webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk [12.03.2018].

APCI (n.d.): Information pack for applicants. URL: apci.org.uk [06.03.2007].

Bakewell, Oliver (2008): »Keeping Them in Their Place«. The Ambivalent Relationship between Development and Migration in Africa. In: Third World Quarterly 29 (7). 1341–1358.

Black, Richard (2001): Fifty Years of Refugee Studies. From Theory to Policy. In: International Migration Review 35 (1). 57–78.

Black, Richard (2003): Breaking the Convention. Researching the ›Illegal‹ Migration of Refugees to Europe. In: Antipode 35 (1). 34–54.

Boswell, Christina (2009): The Political Uses of Expert Knowledge. Immigration Policy and Social Research. Cambridge/New York.

Castles, Stephen (2003): Towards a Sociology of Forced Migration and Social Transformation. In: Sociology 37 (1). 13–34.

Castles, Stephen (2007): Twenty-First-Century Migration as a Challenge to Sociology. In: Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 33 (3). 351–371.

Castles, Stephen / Kosack, Godula (1973): Immigrant Workers and Class Structure in Western Europe. Oxford.

Chimni, B. S. (1998): The Geopolitics of Refugee Studies. A View from the South. In: Journal of Refugee Studies 11 (4). 350–374.

Chimni, B. S. (2009): The Birth of a ›Discipline‹. From Refugee to Forced Migration Studies. In: Journal of Refugee Studies 22 (1). 11–29.

Dale, Iain (2000): Labour Party General Election Manifestos 1900–1997. London/New York.

De Genova, Nicholas (2002): Migrant »Illegality« and Deportability in Everyday Life. In: Annual Review of Anthropology 31. 419–447.

Economic and Social Research Council (2008): Centre on Migration, Policy and Society (COMPAS) Annual Report 2007–2008. ESRC Annual Report RES-573-28-5001. URL: webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk [08.06.2018].

Etzkowitz, Henry (2001): The Second Academic Revolution and the Rise of Entrepreneurial Science. In: IEEE Technology and Society Magazine 20 (2). 18–29.

Exzellenzkritik (2018): Exzellenzkritik. URL: exzellenzkritik.wordpress.com [14.03.2018].

Favell, Adrian (2007): Rebooting Migration Theory. Interdisciplinarity, Globality and Postdisciplinarity in Migration Studies. In: Brettell, Caroline / Hollifield, James (Eds.): Migration Theory. Talking Across Disciplines. 2nd ed. New York / London. 259–278.

Geddes, Andrew (2008). Staff shortages and immigration in food processing. URL: webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk [08.06.2018].

Georgi, Fabian (2014): Making Migrants Work for Britain. Gesellschaftliche Kräfteverhältnisse und ›Managed Migration‹ in Großbritannien. In: Forschungsgruppe ›Staatsprojekt Europa‹ (Eds.): Kämpfe um Migrationspolitik. Theorie, Methode und Analysen kritischer Europaforschung. Bielefeld. 113–129.

Georgi, Fabian (2016): Widersprüche im Sommer der Migration. Ansätze einer materialistischen Grenzregimeanalyse. In: Prokla 46 (2). 183–203.

Gibney, Matthew (2000): Outside the protection of the law. The situation of irregular migrants in Europe. In: Refugee Studies Centre Working Paper Series 6. URL: rsc.ox.ac.uk [16.11.2017].

Good, Anthony (2007): Anthropology and Expertise in the Asylum Courts. Abingdon.

Gov.UK (2016): Independent Advisory Group on Country Information. Gov.UK of 02.12.2016. URL: gov.uk [18.01.2018].

Gov.UK (2018): Migration Advisory Committee. URL: gov.uk [18.01.2018].

Hansard (2003): House of Commons. Draft Asylum (Designated States) (No. 2 Order) 2003. First Standing Committee on Delegated Legislation. 7 July 2003. URL: publications.parliament.uk [12.03.2018].

Hansard (2005): House of Commons. Fifth Standing Committee on Delegated Legislation. 8 February 2005. Draft Asylum (Designated States) Order 2005. URL: publications.parliament.uk [12.03.2018].

Hansard (2009): House of Commons. European Standing Committee B. 19 May 2009. URL: publications.parliament.uk [10.02.2010].

Harvey, David (2007): A Brief History of Neoliberalism. New York.

Hatton, Joshua (2002): Las Raíces Indígenas de la Peregrinación de Jesús del Rescate en Popoyuapa, Rivas. In: Revista de Historia de Nicaragua 14. 61–72.

Hatton, Joshua (2011): How and Why Did MARS Facilitate Migration Control? Understanding the Implication of Migration and Refugee Studies (MARS) with the Restriction of Human Mobility by UK State Agencies. D.Phil. Thesis. University of Oxford, St. Antony’s College. URL: ora.ox.ac.uk [27.09.2017].

Huber, Stephanie / Pettitt, Jo / Williams, Elizabeth (2010): The APCI legacy. A critical assessment. Immigration Advisory Service. URL: refworld.org [27.09.2017].

Imrie, Rob (2010): The Interrelationships between Contract Research and the Knowledge Business. In: Allen, Chris / Imrie, Rob (Eds.): The Knowledge Business. The Commodification of Urban and Housing Research. Burlington. 23–39.

Kleist, J. Olaf (2017): Flucht- und Flüchtlingsforschung in Deutschland: Bestandsaufnahme und Vorschläge zur zukünftigen Gestaltung. Policy Brief 01 (Flucht: Forschung und Transfer. Flüchtlingsforschung in Deutschland). Osnabrück/Bonn. URL: flucht-forschung-transfer.de [17.10.2017].

Latour, Bruno (2005): Reassembling the Social. An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford.

Lucas, Lisa (2006): The Research Game in Academic Life. Maidenhead.

Malinowski, Bronislaw (1932): Argonauts of the Western Pacific. An Account of Native Enterprise and Adventure in the Archipelagoes of Melanesian New Guinea. 2nd ed. London/New York.

Malkki, Liisa (1995): Refugees and Exile. From »Refugee Studies« to the National Order of Things. In: Annual Review of Anthropology 24. 495–523.

Marx, Karl / Engels, Friedrich (1974): The German Ideology. Part One, with Selections from Parts Two and Three, together with Marx’s »Introduction to a Critique of Political Economy«. 2nd ed. London.

Mauss, Marcel (1990): The Gift. The Form and Reason for Exchange in Archaic Societies. London.

Migration Advisory Committee (2008): The labour market impact of relaxing restrictions on employment in the UK of nationals of Bulgarian and Romanian EU member states. URL: ukba.homeoffice.gov.uk [26.10.2010].

Migration Advisory Committee (2009): Review of the UK’s transitional measures for nationals of member states that acceded to the European Union in 2004. URL: ukba.homeoffice.gov.uk [24.08.2010].

Mills, David (2008): Difficult Folk? A Political History of Social Anthropology. New York.

Morgan, Beverley / Gelsthorpe, Verity / Crawley, Heaven / Jones, Gareth (2003): Country of origin information. A user and content evaluation. Home Office Research Study 271.

Mosse, David (2005): Cultivating Development. An Ethnography of Aid Policy and Practice. London.

Parsons, Wayne (2002): From Muddling Through to Muddling Up. Evidence Based Policy Making and the Modernisation of British Government. In: Public Policy and Administration 17 (3). 43–60.

Peutz, Nathalie (2006): Embarking on an Anthropology of Removal. In: Current Anthropology 47 (2). 217–241.

Rietig, Victoria / Müller, Andreas (2016): The new reality. Germany adapts to its role as a major migrant magnet. Migration Policy Institute of 31.08.2016. URL: migrationpolicy.org [15.08.2017].

Schuster, Liza (2005): The continuing mobility of migrants in Italy. Shifting between places and statuses. In: Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 31 (4). 757–774.

Scott, John / Marshall, Gordon (2009): Contradictory class location. In: Dictionary of sociology. Oxford Reference Online. URL: oxfordreference.com [13.10.2009].

Select Committee on Home Affairs (2006): Examination of Witnesses. 12 December 2006. URL: publications.parliament.uk [01.11.2017].

Shore, Cris / Wright, Susan (2000): Coercive Accountability. The Rise of Audit Culture in Higher Education. In: Strathern, Marilyn (Ed.): Audit Cultures. Anthropological Studies in Accountability, Ethics, and the Academy. New York. 57–89.

Slaughter, Sheila / Leslie, Larry (1997): Academic Capitalism. Politics, Policies, and the Entrepreneurial University. Baltimore.

Smith, Neil (2008): Uneven Development. Nature, Capital, and the Production of Space. 3rd ed. Athens.

Tapper, Ted (2007): The Governance of British Higher Education. The Struggle for Policy Control. Dordrecht.

The National Archives (2012): Advisory Panel on Country Information. 3 October 2012. URL: webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk [12.03.2018].

Turton, David (2003): Refugees, forced resettlers and »other forced migrants«. Towards a unitary study of forced migration. UNHCR New Issues in Refugee Research, Working Paper No. 94. URL: unhcr.org [07.07.2008].

UK Border Agency (2008): Skilled, shortage, sensible. The recommended shortage occupation lists for the UK and Scotland. URL: ukba.homeoffice.gov.uk [24.02.2010].

UK Home Office (2001): Bridging the information gaps. A conference of research on asylum and immigration in the UK. URL: webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk [08.06.2018].

UK Home Office (2005): The annual report of the certification monitor, 2004. URL: webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk [08.06.2018].

UK Home Office (2008a): Press release of 09.09.2008. URL: press.homeoffice.gov.uk [24.10.2008].

UK Home Office (2008b): Press release of 11.10.2008. URL: press.homeoffice.gov.uk [24.02.2010].

Wells, Peter (2007): New Labour and evidence based policy making. In: People, Place and Policy Online 1 (1). 22–29. URL: extra.shu.ac.uk [11.01.2018].

Whitehead, Tom (2008): Migrant workers list includes 800,000 jobs. Daily Telegraph of 11.11.2008.

Wolf, Eric (1982): Europe and the People Without History. Berkeley.

Zetter, Roger (2007): More Labels, Fewer Refugees. Remaking the Refugee Label in an Era of Globalization. In: Journal of Refugee Studies 20 (2). 172–192.

This coincidence was noted by the editors of movements in the call for papers for this issue.↩︎

See Hatton (2011: 5–16, 19–21) for a more detailed analysis and critique of this literature. Hatton (2011) is available at the URL listed in the bibliography at the end of this article.↩︎

I understand my analysis to be an example of the use of Latour’s (2005) actor-network-theory. See Hatton (2011: 15–19) for details.↩︎

I am very ecumenical when it comes to social theory; I consider historical materialism to be only one of many legitimate and illuminative ways of understanding the phenomenon of MARS’s harm of its human subjects. Additional interpretations of this relation that are more existentialist, on the one hand, and more structuralist, on the other, are found in Hatton (2011).↩︎

See Hatton (2011: 3–5) for more details.↩︎

My departure from COMPAS was involuntary. I was able to continue my degree at the university because I was a member of St. Antony’s college and received funding not through COMPAS, but rather through the university’s Clarendon Fund.↩︎

See Hatton (2011: 30–37) for a more detailed description of my methods.↩︎

See Hatton (2011: 46–65) for a more detailed description of the growth of MARS in the UK.↩︎

The data upon which the graph in Figure 1 is based are presented in tabular form in Hatton (2011: 367).↩︎

These acronyms stand for the following: ESRC (Economic and Social Research Council), HO IRSS (Home Office Immigration Research and Statistics Service), DFID (Department for International Development), and AHRC (Arts and Humanities Research Council).↩︎

This figure is a conservative estimate for earnings during the six years covered by my sample. See Hatton (2011: 294) for details.↩︎

See Hatton (2011: 405–410) for a more detailed presentation of these data, which I acquired through Freedom of Information Act requests.↩︎

The Refugee Research Centre at the University of East London↩︎

See Hatton (2011: 312–315, 413) for more details.↩︎

See Georgi (2014) for an analysis of UK migration policy since 1997.↩︎

The party’s manifesto for the election famously included the following passage: »New Labour is a party of ideas and ideals but not of outdated ideology. What counts is what works« (Dale 2000: 348).↩︎

See Parsons (2002), Wells (2007), and Boswell (2009) on the importance of the concept of ›evidence-based policy‹ for ›New‹ Labour.↩︎

My findings on the usefulness to the UK Home Office of MARS academics and their research are similar to those of Boswell (2009), who found that expert knowledge on immigration had not only an instrumental function for the Home Office, but also those that were symbolic, which she terms »legitimising« (ibid.: 7, emphasis in original) and »substantiating« (ibid., emphasis in original).↩︎

See Hatton (2011) for more detailed descriptions of these phenomena (ibid. 93–127 and 368–375 for the APCI, and ibid. 127–135 for the MAC).↩︎

The APCI’s website is archived at The National Archives (2012).↩︎

In 2009, the APCI was renamed the Independent Advisory Group on Country Information (IAGCI). I discuss its continuation in a passage below, just before my conclusion.↩︎

University College London↩︎

London School of Economics and Political Science↩︎

See Hatton (2011: 370–373) for more details.↩︎

Ms. Oeppen would go on to become a member of the APCI/IAGCI. For an analysis of the pedagogic assistance that the APCI provided to the Home Office, see Hatton (2011: 121–123).↩︎

See Georgi (2014: 120–122) for more details.↩︎

I have omitted the student’s name.↩︎

Chapter 8 of this report includes the following statement: »We draw heavily on Anderson and Ruhs (2008), which was commissioned by us« (UK Border Agency 2008: 135).↩︎

For similar statements, see Black (2001: 61), Castles (2007: 363), and Favell (2007: 265).↩︎

See also Castles (2007: 363) for a similar statement about sociologists studying migration.↩︎

See Castles (2007: 363) for his statement about pressure to change findings.↩︎

See also the statement in Hatton (2011: 187) by one of Zetter’s RSC colleagues, who told me that Zetter was obliged to join the APCI because he had become the director of the RSC.↩︎

See Hatton (2011: 311–316) for further details.↩︎

My use here of Malinowski and Mauss is, of course, somewhat ironical. By bringing these concepts from the colonial era to bear on my object of analysis, I hope to give my MARS academic readers an epistemological nudge that will encourage them to relativise their own practices and ideas.↩︎

See also De Genova (2002: 439–440).↩︎

This phrase is inspired by Bakewell’s clever title for his article, »Keeping Them in Their Place« (Bakewell 2008).↩︎

See Castles/Kosack (1973: 480–482) and De Genova (2002: 440–441) for additional effects of migration controls that assist in reproducing the subordination of labour to capital. See also Georgi (2016) for an alternative historical materialist interpretation of migration control.↩︎

In 2009, the APCI was renamed the Independent Advisory Group on Country Information (IAGCI). At the time of writing, its chair (Dr. Laura Hammond) and four »independent members« (Dr. Ceri Oeppen, Dr. Elena Fiddian-Qasmiyehare, Dr. Michael Collyer, and Dr. Patricia Daley) were MARS academics (Gov.UK: 2016). Also, at the time of writing, the MAC’s chair (Prof. Alan Manning) and two (Prof. Jackline Wahba and Ms. Madeleine Sumption) of its three members were MARS academics (Gov.UK: 2018).↩︎

They are Prof. Daley of Oxford, Dr. Collyer and Dr. Oeppen of Sussex, and Dr. Fiddian-Qasmiyehare of UCL.↩︎

Ms. Sumption directs the Migration Observatory at COMPAS.↩︎

They are Dr. Fiddian-Qasmiyehare and Dr. Collyer, respectively.↩︎

They are Prof. Manning and Ms. Sumption, respectively.↩︎

See Kleist (2017) for a description of funding for MARS projects.↩︎

For a critique of this program, see Exzellenzkritik (2018).↩︎

See Rietig/Müller (2016) for a summary of German asylum and immigration policies.↩︎

My first manuscript submission to the editors of movements did not include a discussion of whether or not a ›critical‹ MARS might be possible, but it was made clear to me very early on in the editing process that followed that I would be expected by the journal’s audience to address the issue. I added this final, reflective section to the essay in an attempt to respond to this demand.↩︎

The awarding of the fellowship was, I think, also based on the thesis research topic that I proposed in my application: a comparative study on the adaptation and political consciousness of Mexican migrants in the USA and Algerian migrants in France.↩︎

For a discussion of surveillance and MARS in the UK, see Hatton (2011: 135–156, 286–290, 411).↩︎

The full name of Kritnet is Netzwerk kritische Migrations- und Grenzregimeforschung.↩︎