Abstract In March 2018, Bihać, a city located in the northwestern corner of Bosnia and Herzegovina, emerged as the newest »hot spot« on the so-called »Balkan migrant route«. This is due to the city’s proximity to Croatia and thus the European Union’s (EU) border, and because of the closing of borders and routes elsewhere in Europe. The city is currently harboring around 3,000 people from South Asia, the Middle East and Northern Africa who are trying to cross into Croatia and the rest of the EU. While waiting to cross into the EU, these individuals navigate and manage everyday living with, next to, and among the people of Bihać. In this account, I attempt to capture some of these dynamics by focusing on multiple encounters between the people of Bihać and migranti with a special focus on the local people’s perspectives.

Keywords Migrant crisis, nature, infrastructure, Bihać, Bosnia and Herzegovina

In March 2018, Bihać, a beautiful yet devastated city located on the northwestern edge of Bosnia and Herzegovina near the Croatian border, emerged as the newest »hot spot« on the so-called »Balkan migrant route«. This is due to the city’s proximity to Croatia, and thus to the European Union (EU), and because of the closing of borders and routes elsewhere in Europe. The city is currently harboring approximately 3,000 people from South Asia, the Middle East and Northern Africa who are desperately and repeatedly trying to cross into Croatia and the rest of the European Union.1 While some successfully cross the rivers, streams, fields, and mountains dotted with landmines and heavily patrolled by the Croatian police, new people arrive daily, hoping to eventually cross the same border. The human flow of weary bodies and bruised souls continues, fragmented and ridden with deadly obstacles.

In the meantime, while waiting to cross into the EU, these individuals navigate and manage everyday living with, next to, and among the people of Bihać with support from local people, Bihać’s Red Cross, the International Organization for Migration (IOM), and with little help from the Bosnian state or the Federal government. The situation is further complicated due to the fact that many Bihać people were refugees during the Bosnian war (1992-95) and thus (claim to) »know what it is like to feel violently uprooted, displaced and unwanted«. This propels many to help migranti (migrants) while simultaneously wishing them gone. These seeming contradictions, layered distinctions, and experiences of refugeeness create unique convergences of people and histories in Bihać.

In this account, I attempt to capture some of these dynamics by focusing on multiple encounters between the people of Bihać and migranti with a special focus on the local people’s perspectives. In the process, I reveal how larger geo-political restructurings—including capitalist extractions and political upheavals—and their violent manifestations unfold within the city. While there are numerous academic and journalist accounts attempting to make sense of, historicize, and/or humanize the »migrant crisis«, this contribution is not directly concerned with that body of literature. Furthermore, the sections and vignettes in this article do not have consistency—some are written as specific entries on a particular day, and others are more of a meditation/reflection. Some are personal and some more sociological or analytical.

I attempt to create a mosaic of these seemingly disconnected and abrupt notes from the field—vignettes and fragments of social life—in order to portray the ways in which these encounters articulate themselves in the unique context of Bihać. These new encounters require new grammars—layered, coded, and reshuffled local meanings and historical artifacts—that are often overlooked in academic writings and journalistic accounts. Some of these new idioms include war analogies (Srebrenica, Gaza, Partisan Cemetery, and AVNOJ2), nature (rivers and trees), and infrastructure (ruinous socialist buildings and public spaces). By focusing on these local articulations, discursive spaces, and historical conjunctions—which materialize in relation to the new world (dis)orders—I offer a brief account of what coming together, living together, and surviving together feels like and looks like from the perspective of a citizen of Bihać who lives elsewhere, but who annually and loyally returns to the city.

Positionality/Reflexivity

I was born in Bihać in the 1970s. A unique Yugoslav brand of socialist self-management—its ideologies, political economies, and socialites— profoundly shaped my view of the world. I was 16 years old when my home town was violently besieged by the »Serb army«; a blockade that would last for over three years. I witnessed a painful, material, and deeply visceral transformation of an industrial, socialist, and relatively progressive town into a town choked by a three and a half year-long siege. The town’s population changed drastically during the war and so did its streets, which transformed from places of tireless social gathering to ghostly zones of abandonment (Biehl 2005) covered with »human waste« (Bauman 2003) and non-human rubble (Stoler 2008). After the war ended, people who survived the siege, either in town or in exile, returned to the streets and ›normal‹ life, however changed, returned in the city. At the same time, socialist infrastructure—buildings, industrial zones, social services, and public spaces—continued to decay and peel off, generating frustration of local populations and corrective narratives to the popular »western« discourses of linear, regional postsocialist transitions from socialism and war to democracy and peace (see Hromadžić 2019). Even though I moved to the US in 1996, I continued to visit the town and its people and places annually, witnessing their often complicated postwar and postsocialist alterations. What follows is deeply rooted in and colored by my unique experience of socialist Yugoslavia and the Bosnian war.

Notes from the Field

Wars (June 2018)

Today, Bihać looks different. It has been a year since my last visit and this time the town appears uncanny—familiar but not mine. While I have witnessed many transformations of Bihać in the last three decades, I was, yet again, caught unprepared, intellectually and emotionally, for this most recent change. The main public spaces—parks and the river’s banks—are layered with groups of devastated people, the »global outcasts« or »human flow«. They are mostly young males, products of war-generated violences and of »savage sorting«—the destruction of more traditional forms of capitalism by more advanced capitalist forms in much of the world (Sassen 2010). They are sitting in parks, usually on the grass, suspended in their waiting to cross into the EU. Some are sleeping in larger groups next to each other, the bags, their only possessions, under their heads. Stray dogs, another symbol of Bihać’s postwar »transition«, are roaming around them. While walking next to these sleeping and resting bodies, I start to grasp and embody the seemingly contradicting sentiment that people in Bihać have been articulating for months: on the one hand, there is a genuine empathy and desire to help the unfortunate people on the move whose lives were transformed—by global capitalist economies and contemporary warfare—into the »scum of the Earth« (Arendt 1951: 267). On the other hand, the local people, devastated by catastrophic unemployment and political impasse, are genuinely terrified of »losing« the last places that bring moments of joy and an appearance of »normalcy« (see Greenberg 2011, Jansen 2015) to town: its beautiful river Una and numerous other public spaces of socialization, such as parks and pedestrian streets dotted with coffee shops. The sight of ›elsewhere‹ people, who out of necessity and misery ›colonized‹ Bihać’s public spaces and river banks, and their undeniable, evident suffering felt devastating, unbearable, and dystopic to many people. This convergence created the ›limit‹—existential, emotional, and semantic.

Not that I was not warned. When I called a friend several days prior to my arrival and asked: »What’s new in town?« she responded, unhesitatingly: »There are many new tamnoputi [dark skinned people] here. Azra, they are everywhere.« Her racist and xenophobic comment paralyzed me for a moment; I caught myself judging her. Now, however, I find myself avoiding certain— central—parts of the town, remapping the city. I am not alone. Many of the people I converse with tell me that they do not move around the city the same way anymore. Rather, they avoid certain routes and create new ones. »You know what it is like? It feels just like that time right before the war started« one acquaintance remarked. »Remember the atmosphere? We were all tense, confused. We were saying: ›This cannot be happening to us!‹ That is how it is now. We do not nonchalantly stroll around town anymore like we always did. Rather, we move with purpose, we walk quickly. We go from point A to point B. We lock our homes and our fences. We do not go out much at night. No one strolls anymore.«

This link between the perception of current danger and the pre-war atmosphere is only one of many ways in which people in Bihać understand and live their new predicament. The trope of war emerged in multiple conversations and bodily practices. First, the people used their experiences and memories of the Bosnian war to paint themselves as different, better, and more understanding than other states and nations, which mistreated and rejected migranti. Rather, people I talked to often stressed that they—who themselves were shot at and made into refugees two decades ago—understood the refugee predicament. And this sentiment did show in instances in which ordinary people dressed and fed migranti, saving their »bare lives« (Agamben 1995), while not necessarily wanting to get to know them as individuals with particular histories and struggles. Rather, migranti were seen as a bare, dark skinned sea of humanity (Malkki 1996) that embodied and displayed universally recognized forms of human suffering, while confusing some categories of bare humanity (the ideal, innocent sufferer is a socially isolated, apolitical, teary eyed black African child who stares at us from the UNICEF’s flyers, or a young, dark skinned, sexually assaulted female. These ›new‹ migranti, however, are mostly young, able-bodied dark skinned males, equipped with cell phones). At the same time, these visibly suffering humans were being stripped of their sociality and historical particularism. They were simultaneously made into superhumans (suffering) and dehumanized (people with no name or historical ›roots‹) because their social and political struggles—their real life (his)stories—were uninvited and thus made invisible in the name of shared and bare humanity (see Malkki 2017). This recognition and stretching of categories (»bare life« and »suffering, universal human«) allowed the people in town to simultaneously feel for migranti and wish them gone.

The Bosnian war(s) and the current predicament of refugees and migrants from the Middle East, North Africa and South Asia found their convergences in other unexpected and historically potent ways. One day, my friend and colleague, who also lives and teaches abroad, was passing by Borići (Small Pines), a forested area near the then largest migrant encampment in Bihać. He spotted migrants sleeping in the Partizansko groblje (Partisan Cemetery), which was built during socialism to honor those Yugoslav Partisans of Bihać who were killed during World War II. Migrants took naps and rested next to these graves, creating novel historical intimacies and layers of bones and flesh, cement and grass, visible and invisible names, lives and deaths.

Another day, as I was walking through Aleja, an alley of trees next to the Partisan Cemetery at the end of which many migranti found their precarious shelter in an unfinished, socialist-built student dorm, two migrants from ›who knows where‹ walked in front of me. One of them wore a white shirt given to him from ›who knows whom‹. The back of the shirt read: »Srebrenica – da se ne zaboravi genocide« (»Srebrenica—never forget genocide«). This painful overlapping and literal collapsing of the Bosnian war’s most painful history of the Srebrenica genocide, when more than 8,000 Bosniak men and boys were captured and killed in three days by the Serb Army in the UN Safe Zone of Srebrenica in 1995, and the history of violence, exclusion, and despair that brought the shirt-wearing migrant to Bihać was devastating; it created both a limit of the comprehensible and tolerable, and it marked an excess of suffering.

Nature (July 2018)

Some of the most important symbols of Bihać are its famous Una River and its surrounding trees and forests. In this most forested European country, which ›hides‹ some of the last and biggest fresh water repositories in Europe, Bihać is exceptional due to its greenness. The Una River is famous for its beauty3, fast currents, emerald color, water quality, tourist potential, and for keeping Bihać’s population sane and safe during the 1990’s war. The link between the people and the river is socially produced and exceptionally strong. As one resident told me: »Without her [the river], I would not know who I am. She makes me sovereign.« Another added: »If I were to be born again… I would like to be a fish, so that I can live in the river.«

The river flows through the very center of town, both dividing and uniting it. It should therefore not be surprising that the majority of migranti spend their time around the river. For many of them, the Una River provided the only source of hygiene and, possibly, moments of joy. The residents of Bihać were both understanding (»Where else would they go to wash?«), inclusive (»They know how to properly use public spaces!« exclaimed one local architect in awe), and alarmed. These alarming discourses were multidimensional, often combining compassion and racism, and xenophobia and care. For example, one person exclaimed: »I fully understand that they have to wash their clothes and their bodies [in the river]. They have no access to bathrooms and showers. But this river is so clean, we protected it. We do not wash clothes in it anymore because we know that detergent is bad for the fish.« Here, migranti were seen as both needy and polluting invaders—contaminating the sacred, socially produced bond between humans and non-humans, people and the river.

Another alleged migrant practice provoked an outcry: eating the river’s ducks (Degirmendžić 2018). The Una River harbors many of these animals, which are ›consumed‹ by the local people in the city as attractions, but never as food. These city ducks, ›our ducks‹, are often (problematically) fed bread by the locals, especially children. (There used to be two swans in the river as well— the first postwar mayor, I was told, illegally smuggled them from Italy). Simply put, the river’s ducks are the locals’ pets. The idea of migranti, »catching and roasting ducks at the banks of the river«, was the limit to many. While some people saw these practices as a desperate move of hungry people, others saw this as a sign and confirmation of their incivility and backwardness: »It is possible they are eating [our] ducks. I would not be surprised if they were to start eating each other«, whispered one local man (Degirmendžić 2018).

The river’s banks and lush vegetation also offered secluded spaces for refugees and migrants to defecate. One day, as we were walking by the river, two friends and I tried to maneuver this ›mess‹. A friend remarked, »This is Put govana! [the Road of Shit!]«. He was alluding both to the path by the river covered in migrants’ feces that we were navigating, and the parallel road on the other side of the river known as Put AVNOJA. This Put AVNOJA was built during socialist times and it connects western and eastern Bosnia. It is possibly the second most frequented road in the country. Contrasting Put AVNOJA and the Road of Shit, the friend was bringing together two seemingly disconnected and incommensurable experiences and uneasily converging histories—socialist modernity and development on the one hand, and the contemporary ›migrant crisis‹, infrastructural ruination, shit, and decay on the other.

The river was not the only natural landmark around which tension born out of forced coexistence between the local population and migranti was articulated. Borići, a forested area near the largest migrant encampment in Bihać at the time, became another conflicting space of lament and compassion, xenophobia and critique. This area, adjacent to the main soccer stadium, was forested by the socialist youth in the seventies and eighties of the last century. Several years ago, the Extreme Sports Club »Limit« remodeled the space and converted it into a well-kept nature walk and exercise path where many locals escaped the city’s dust to breathe some fresh air. In March 2018, this area, however, became the main space where several hundred migranti created a make-shift camp dotted with improvised tents. This camp emerged in and around the former student dorm— a symbolic postwar and postsocialist ruin of the future past4—tacked in behind the exercise path. Images of the Borići’s trees being stripped down of their bark (for heating purposes) provoked an outcry among those who planted the trees and others who lamented the »lungs lost«. Others were upset »with those among us who forget what it is like to be a refugee«. An American acquaintance, seeing my images of the »naked« trees, and without knowing much about the context, asked me nonchalantly: »Are these pine beetles?«, alluding to an invasive species that attacks pine trees. This question literally collapsed the boundary between the human and non-human, where migranti and »invasive others« (Ticktin 2017: xxiii) collapsed into one, dangerous category.

Infrastructure (July 2018)

When I visited Bihać in the early summer of 2018, one of the main places where migranti were temporarily staying was a never completed socialist retirement home or Dom penzionera located on the banks of the Una River in the center of Bihać.

The building remained eerie and skeleton-like for decades, a shadow and a symbol of the unmaterialized socialist past and the perpetually transitioning postwar present. More specifically, over the last 25 years this unfinished building, instead of its imagined inhabitants—elderly socialist workers who were going to age and die in it peacefully—has been housing and co-producing multiple unexpected residents: the transition’s »wasted humans and human waste« (Bauman 2003). These residents include disillusioned Bosnian youth and, more recently, migranti (see Hromadžić 2019).

Dom’s ruinous, dangerous, skeletal structure was, at the time of my visit, occupied by several hundred refugees and migrants. The conditions in the building were unhygienic and structurally unsafe, highlighting the forms of precarity and despair that enveloped these migrant lives. The extremely unfavorable social (over-crowdedness and internal disputes) and material conditions born out of Dom’s dangerous physicality, continued to produce violence and death, including the death of a 37-year-old man from Afghanistan who fell through the open elevator shaft and broke his spine, which lead to his death (Faktor.ba 2018). Five days after that tragedy, another young man lost his life while swimming in the nearby Una River. These tragedies point at yet another non-linear historical twist: instead of the socialist worker-pensioners, who were supposed to age slowly and peacefully next to the florescent and calming Una River, the lives of young male migrants from the Middle East, South Asia and North Africa were being violently taken by its currents (Krajina.ba 2018; see Hromadžić 2019).

Planet Sarajevo (October 2018)

For the most part, Bišćani (citizens of Bihać) do not blame migranti for the overwhelming situation in their town. Rather, they blame ›Europe‹ and the Bosnian government in Sarajevo. They have witnessed their city being overwhelmed with refugees, more so than any other town or city in the country. While this is a state-wide problem, they feel the state does not help them. The situation in which hundreds of new people are coming through Bihać daily trying to cross into Croatia, has overwhelmed the city of 45,000 inhabitants, which is already dealing with (post)war destruction, high poverty, extreme unemployment, and infrastructural ruination. The people of Bihać once again feel betrayed by Sarajevo and Sarajevo-oriented politicians for neglecting both them and the refugees. They recount ways in which »the government in Sarajevo tries to channel migranti to Bihać [and the rest of Una-Sana Canton in which Bihać is located] just to get rid of them and send them to us. And we want to help them. But government in Sarajevo is not helping us help them. They just encourage them to take buses and trains to Bihać, and they leave the rest to us. What kind of government does that?« People in Bihać feel uncared for by their government as well as misunderstood, alone, and exhausted.

Months of this bubbling emotion lead to a protest in October 2018. The protest was interpreted by many, including Sarajevo-based and European media and publics as well as civic society groups within the region, as anti-immigrant, racist, and xenophobic. Many local people were shocked by these misreadings; while some anti-immigrant and racist sentiment was present and clearly articulated in one of the signs visible at the protest, which read »Immigrants Go Home« (and not accidentally, this was the main image that circulated through social media), painting the protest as such is too simplistic. I was repeatedly told that the main target of the protest was not migranti but the Bosnian government in Sarajevo which is »doing nothing« for Bišćani who deal with the crisis daily. The town was at the brink of collapse, and a »humanitarian catastrophe«, and Bišćani felt those in Sarajevo did not care.

This feeling of being neglected by Sarajevo was then linked to the experience during the war (1992-95), when the people in the besieged region of Bihać felt similarly abandoned by the central government. In 1993, during the Bosnian war, Fikret Abdić—a local businessman turned politician from a town located 60 kilometers north of Bihać—and his followers declared independence from the Bosnian government in Sarajevo and its army. Immediately they began cooperating with Serb forces in Bosnia and Croatia which besieged the region for more than a year at the time. This further aggravated the situation in the Bihać region, which was split into two halves (a pro-government one and a pro-Abdić one) that started a war against each other. This propelled some in Sarajevo to see the people in the Una-Sana Canton as traitors. The people’s protest in Bihać in 2018 built on this uncomfortable history of exclusion, abandonment, and betrayal, and it linked that long-lasting sentiment to the contemporary, unexpected, migranti-related predicaments. The protest was therefore another attempt by Bišćani to interpellate the government in Sarajevo to respond and move to action. People asked the government to »appear« with a plan and a vision of the future. They demanded a »system«, but as a result, the protest organizers were fined for organizing the protest. People were shocked, hurt, and angry. In the local people’s opinion, their actions were, however, misunderstood and misinterpreted as anti-immigrant, even racist, and once again they felt abandoned. That is, until Europe »showed up«.

Fortress Europe and Bosnian Gaza Strip (Fall 2018)

In the fall of 2018, a series of meetings took place between the Cantonal Minister of Education in Bihać and the parents of children enrolled in the elementary school Brekovica in the village with the same name located some eight miles from Bihać. The meetings revolved around one main issue: education of »migrant children« from the nearby hotel Sedra. The hotel has recently been remodeled by the IOM in order to house 300 migranti with children. The presence of IOM in Bihać reminded people of the heavy yet complicated involvement of the »international community« in postwar reconstruction after the Bosnian war ended. This ambiguous and insufficient presence of Europe was yet another link between the war and the current predicament.

The issue arose when the children from the ›hotel‹ had to start school. According to The New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants (2016) that paved the way to the adoption of two global compacts on migration and refugees in 2018, education is a critical element of the international refugee response. Many local people were aware of this, but once they were faced with the ›problem‹ of migrant children attending ›their‹ school, they threatened to pull their children out of school. As one parent said: »Of course the migrant children need education. But they are living in such unhygienic conditions, our state and the world are not really helping them … And all we want is to make sure that there is no spreading of diseases… . We also have to protect our children.«

Seeing this parent discuss this issue on a local TV channel, a friend commented: »Of course… . inclusive education. But they [Europe] are so hypocritical. They built their Fortress [Europe], they put their security cameras, police, barbwire and cannons on their border… and every time these same children try to cross, that same Europe sends them back to Bihać and our canton. But they are scolding us for not educating them! Isn’t that hypocritical?« What these remarks illuminate is the politics of »armed love« (Ticktin 2011: 161) where care replaces cure (Ticktin 2011) and where the moral imperative to act is accompanied, explicitly or implicitly, by practices of violence, exclusion, and containment. Many of the people in the region felt this double, hypocritical nature of ›European care‹ that was turning Bihać into, as one acquaintance remarked, the ›European Gaza Strip‹. This seemingly unexpected and unfounded comparison of Bihać and Gaza is a perceptive commentary on the contemporary forms of savage sorting and transformation of certain world geographies—and people historically attached to them—as spaces of misery and »bare life« (Agamben 1995). These regions are besieged by palpable, militarized borders, where contemporary »human and non-human waste« is dumped, monitored, and (attempted to be) depoliticized and contained.

Another Bišćanin explained further: »On the West side, you have Europe with its barbwires, its walls, its security apparatuses. On the East side, you have Sarajevo and its government, which is doing everything to get rid of migrants by sending them to our canton. They encourage them to come here. And we are struggling with our own issues. But both sides are accusing us to be racist and xenophobic. Isn’t that crazy? And we are actually the ones feeding the migrants and living with them, trying our best to coexist somehow.« Commenting on this situation, another person told me: »Did you know that Croatia closed the border crossing with Bosnia [the entry point near Velika Kladuša, another town in the Canton with a big refugee and migrant population] for a few days because of the hectic migrant situation? We are turning into Gaza, where they [the West] will dump all the migrants they catch in Europe. They even bring here, to us, those migranti that never passed through Bosnia on their way to Europe. That is illegal!… . Yes, they will give us some money for infrastructure [IOM invested some funds in repairing tokens of infrastructure in the city] and then, they will make us into a dumping ground.«

This idea that Bihać and its canton are being sacrificed by both Europe and Sarajevo and turned into a European Gaza—a forcefully enclosed dumping ground for modernity’s »global outcasts« that are understood as dangerous, racially marked, and strategically produced as superfluous populations—was wide-spread in Bihać. It is here that the overlap of dispersed peripheries—Gaza and Bihać - and postwar, postsocialist, postcolonial, and imperial geographies and histories, forcefully converged to challenge our analytic vocabularies, research methodologies, and attempts to create clean categories of analysis. These painful, unexpected and highly visible convergences of seemingly incongruent bodies and souls, political bureaucracies, resistance, diplomatic strategies, humanitarian regimes, and economic calculations revealed new world orders, encounters, and experiences. These intimate convergences especially exposed the nature of politics of European care, which offer only a temporary and superficial fixing of »wounds«. Furthermore, it disclosed the European morality of »armed love«; regimes of exclusion and punishment emerging in the name of human rights, compassion, and inclusion (Ticktin 2011).

The Game (March 2019)

On an exceptionally warm and sunny afternoon, a friend and I were watching a soccer game at the main stadium in Bihać. Jedinstvo, the local team with long tradition, notable past and unremarkable present, was playing against the team from Herzegovina today. The game was painful to watch: the quality of the team was declining together with the city itself. The stadium is located in Borići. Due to the proximity of the IOM-run migrant camp—a partially renovated ruin of the former student dorm—to the stadium, migrants became regular fans at these games. On this day and any other day, they were vocal supporters of the team loudly cheering in those rare moments when Jedinstvo scored.

Migranti usually sit on the north side of the bleachers right next to the city’s most vocal and incident-prone fans. The stadium is in a state of ruins and ruination. It is yet another token of decaying socialist infrastructure— another ruin of a future past—and its socio-material »living, breathing, leaking assemblage of more than human relations« (Anand 2017: 6). The IOM, following its twisted logic of humanitarianism, committed to repairing some of the stadium’s decaying infrastructure and has already begun with the works. This added another layer of ambiguity to the already complicated relationship between the local people, the refugees, and Fortress Europe.

The local team barely won. As we left the stadium, we encountered another group of migrants walking towards us on their way to the Plješivica Mountain. Their steps were determined and in sync. They walked in an army marching formation— their steps regular, ordered, and synchronized. They carried backpacks and sleeping bags, and they walked faster than the rest of us determined to cross the mountain into Croatia. Migrants call this attempt to cross into Croatia »The Game«. One of multiple explanations for this name is that the whole experience resembles a cat and the mouse game. As they ›play‹ the game they often get caught by the ›cat‹—the Croatian police—which is heavily patrolling the mountain. »It is interesting« my friend remarked, »that they are using the same route to cross that we used to illegally cross into Croatia during the war to escape the siege«. This comment collapsed the time/geography between the two events. Refugees, near and far, blended into a sea of walking humanity, »the flow of humans«, seemingly without history. I imagined this group, marching in their decomposing tennis shoes, sleeping in the snow-covered, landmine-decorated mountain that night.

If they are captured, they will most probably be beaten up by Croatian police and forcefully returned to Bihać. Their few possessions will be taken. And then they will try again, sometimes over ten times, until they finally reach what one refugee called »a place of peace« in the Fortress Europe, which is decorated with the discourse of human rights and politics of barbwire. Or they might freeze in the snow-covered mountain never to be identified. It is a game, after all.

Landfill, Landmines and the Wolfs (July 2019)

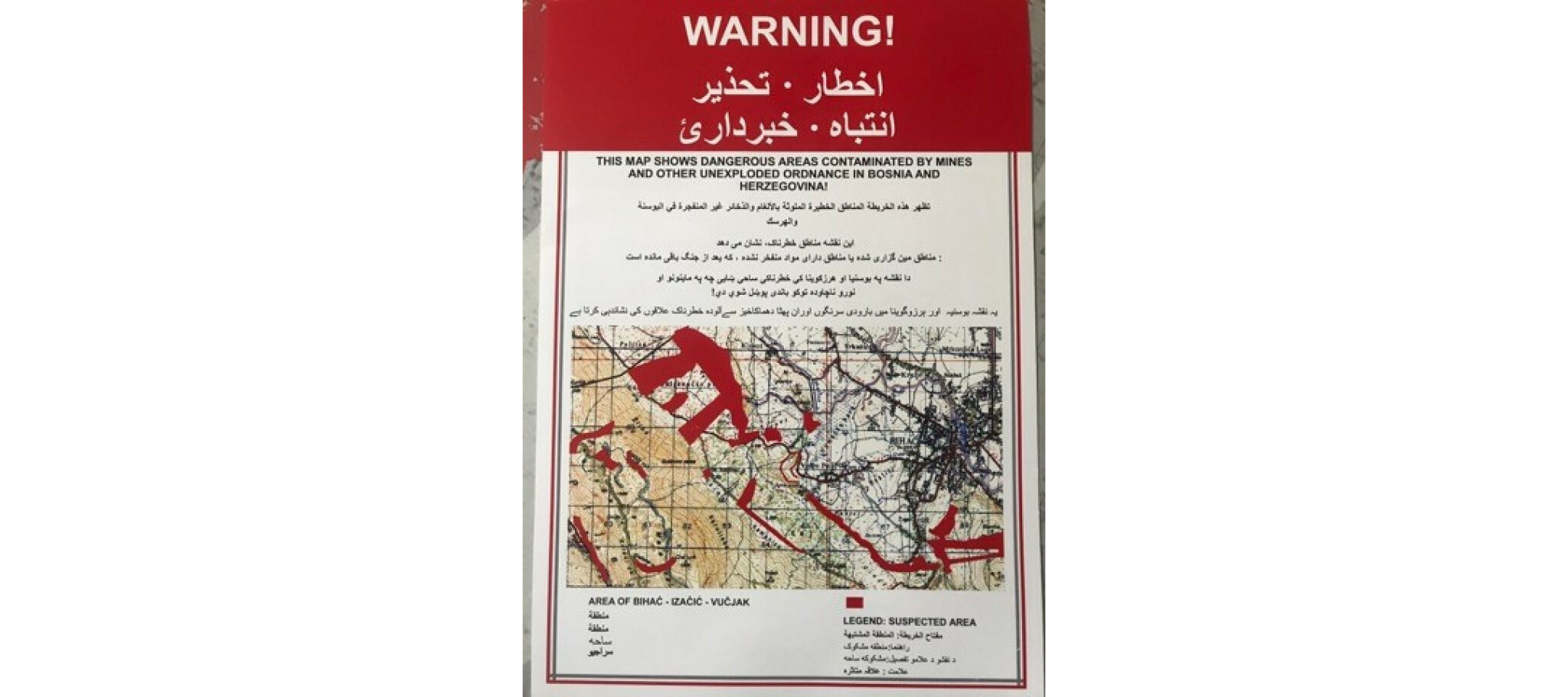

In July 2019, I returned to Bihać. This time, the town was quiet and eerie. I walked its streets, measuring its silences and sensing the heaviness that often accompanies the proximity of human tragedies. Soon, I learned that after more than a year of waiting for the Bosnian state, Europe, or any other actor to help them manage ›the migrant crisis‹, further propelled by several instances of violence between different, antagonistic migrant groups in town, in June 2019, the City of Bihać and the Una-Sana Canton singlehandedly started forcefully removing migrants from their semi-licit, crowded, and in apt dwellings. While some local residents protested this »hunt on people«, others in town welcomed this intervention. One person told me enthusiastically: »We took our city back. A day after the migrants were relocated, I went out with friends. We were all dressed up; I even put on lipstick, and we had coffee in the very center of town.« While welcoming this »take over«, many people were very concerned about the means of forceful removal of people and the inhumane location of the new camp. The migrants were sometimes patrolled by the police and made to walk for six kilometers in a prisoner-style single file formation with their right hand on the shoulder of the man in front of them. After a public outcry about these practices, which were reminiscent of war, refugeeness, and imprisonment, migranti were bused out of town to the forest clearing, a former communal landfill located six kilometers from Bihać near the village of Vučjak in the foothills of the heavily mined Plješivica Mountain.

Vučjak etymologically stems from vukovi or wolfs, connoting a daunting space where wilderness and animals dominate over humans. The rumor has it that the city government decided on this problematic location in order to provoke some response from the irresponsive Bosnian state and passive, hypocritical, and moralizing Europe. As a local professor told me, »no one expects this to last. There is no way migranti could survive the winter there. They will be relocated again.«5 Both the Bosnian government and many EU and international bodies, NGOs, and media outlets condemned the choice of location (citing both the violation of human rights and fear that the camp was physically too close to Croatia) while failing to offer, so far, any concrete solution, recommendation, or assistance. Most care, including two daily meals, come from local people and the local Red Cross. Meanwhile, Vučjak became yet another »jungle« produced at the intersection of near and far violences, and Bišćani’s despair and their historically rooted sense of disappointment in the Bosnian government and the world/Europe »that keeps on looking«.6 These forces generate dehumanized (im)mobile humans—suspended in time and space—who are literally sleeping and waiting on tons of toxic garbage, surrounded by still unexploded landmines from the most recent war (there were three explosions near Vučjak since the war ended), and encircled by wolfs. What is more, this heavy human activity on top of the landfill is producing untreated human waste, feces, and garbage, which are seeping into the porous soil. According to some experts and experiments, these contaminants need less than a day to travel underground to reach one of the main fresh water springs in the town of Klokot ironically circling back into the bodies of local people. These anxieties produce new convergences of local people and migranti as well as new water markets and habits, expert knowledge, (non)governmental projects, deeper political resentments and accusations, bodily concerns, and precarious, unsettled and unfinished ways of being in the world.

Literature

Agamben, Giorgio (1998): Homo Sacer. Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Palo Alto.

Anand, Nikhil (2015): Accretion. Theorizing the Contemporary. Fieldsights of 24.09.2015. URL: culanth.org [29.10.2017].

Arendt, Hannah (1951): Origins of Totalitarianism. New York.

Bauman, Zygmunt (2003): Wasted Lives. Modernity and Its Outcasts. Cambridge.

Biehl, João (2005): Vita. Life in a Zone of Social Abandonment. Berkeley/Los Angeles.

Degirmendžić, Semira (2018): Migranti roštiljaju patke na Uni, Bišćani zgroženi. Dnevni Avaz of 5.7.2018. URL: avaz.ba [11.07.2019].

Faktor.ba (2018): Bihać. Afganistanac slomio kičmu pri padu sa »Doma penzionera«. Faktor.ba of 2.7.2018. URL: faktor.ba [20.08.2019].

Greenberg, Jessica (2011): On the Road to Normal. Negotiating Agency and State Sovereignty in Postsocialist Serbia. In: American Anthropologist 113(1). 88–100.

Hromadžić, Azra (2019): Uninvited Citizens. Violence, Spatiality and Urban Ruination in Postwar and Postsocialist Bosnia and Herzegovina. In: Third World Thematics: A TWQ Journal.

Jansen, Stef (2015): Yearning in the Meantime. »Normal Lives« and the State in a Sarajevo Apartment Complex. New York/Oxford.

Koselleck, Reinhart (2004): Futures Past. On the Semantics of Historical Time. New York.

Krajina.ba (2018): Nesretan slučaju Bihaću. Ugušio se migrant prilikom kupanja u Uni. Krajina.ba of 5.7.2018. URL: krajina.ba [13.07.2019].

Sassen, Saskia (2014): Expulsions. Brutality and Complexity in the Global Economy. Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Stoler, Ann (2008): Imperial Debris: Reflections on Ruins and Ruination. In: Cultural Anthropology 3(2). 191–219.

Ticktin, Miriam (2011): Casualties of Care. Immigration and the Politics of Humanitarianism in France. Berkeley.

Ticktin, Miriam (2017): Introduction. Invasive Pathogens? Rethinking Notions of Otherness. In: Social Research: An International Quarterly 84(1). 55–58.

s. n. (s. a.): Una, Spring of Life. s. l. [brochure produced with assistance from European Union through the Croatia-Bosnia and Herzegovina Cross-Border Cooperation Program 2007-2013]. URL: unaspringoflife.com [13.09.2019].

This number is an estimate. No one in Bihać could tell me how many »people on the move« were there exactly—some local Red Cross workers estimated that there are around 5,000 individuals in Bihać at the moment, but others saw that number as too high.↩︎

Bihać’s Partisan Cemetery was built after WWII in honor of the Yugoslav Partisans of Bihać who were killed during WWII. Bihać was embedded in history as the place of the First Session of the Anti-Fascist Council for the National Liberation of Yugoslavia (AVNOJ) where, on the 26th and 27th of November 1942, the future post WWII Yugoslavia was first postulated.↩︎

According to the legend, Una was named by Roman legionaries who, upon seeing it for the first time, exclaimed: »Una! – One and only!« (s.n. s. a., page 1).↩︎

The phrase »future past« is the construction of Reinhart Koselleck (2004), a historical theorist who in his famous work Futures Past: On the Semantics of Historical Time explores, among other things, the experiences of the past that impose modernity.↩︎

The camp was indeed closed on December 10, 2019. Most individuals from Vučjak were bussed to Ušivak, a village close to Sarajevo.↩︎

I use »jungle« here to make a connection between Vučjak and the »Calais« jungle in France. Between 2015 and 2016 this area was a large, controversial and globally well-known refugee and migrant camp near Calais, France.↩︎