Abstract Since mid-2018 Slovenian border police systematically denies asylum seekers’ rights and deports individuals who declare intention to apply for international protection. After first testimonies about push-backs published by deported individuals and solidarity volunteers based in Bosnian border towns, activist collective Info Kolpa established an info phone with an aim to monitor police procedures on the border. It allowed to communicate with people on the move that are trying to reach chosen destinations traveling through Croatia and Slovenia. The article discusses push-backs on the Slovenian-Croatian border and the attempt of the activist collective to make criminal police practices visible and to support people on the move.

Keywords Slovenian-Croatian border, police violence, push-backs, info phone, monitoring

The border between Slovenia and Croatia is a Schengen border. Since late 2015 and the beginning of 2016, it has been militarized with hundreds of kilometers of fence that covers more than one third of the border’s total length and with a significant presence of police and even the army, which is granted police authorization in case a two third majority of the national parliament declares an emergency at the border. There have been consistent attempts by successive governments, which, at least for now, have been blocked by the Constitutional Court, to pass legislation allowing to seal the border in case of a significant increase of asylum seekers, i.e. to completely suspend the right to seek international protection in Slovenia. Besides this, the patrolling of right wing paramilitary groups—so-called vardas—along the border is tolerated, if not even encouraged. The goal of such anti-migrant measures and policies lies in discouraging asylum seekers to apply for asylum in Slovenia as the first Schengen country (besides Hungary) on the Balkan route. This intention is widely supported by a vast majority of established political parties, regardless of their ideological affiliation, their oppositional status, or them being in government. This is the reason why the criminal and systematic rejection of the right to asylum by the Slovenian police, which we describe in this text, does not become a topic of highest public concern. To oppose the systemic violence of the police against people on the move and violent attempts to close the borders, we initiated Info Kolpa whose experience is another topic of this text.

Push-backs from Slovenia

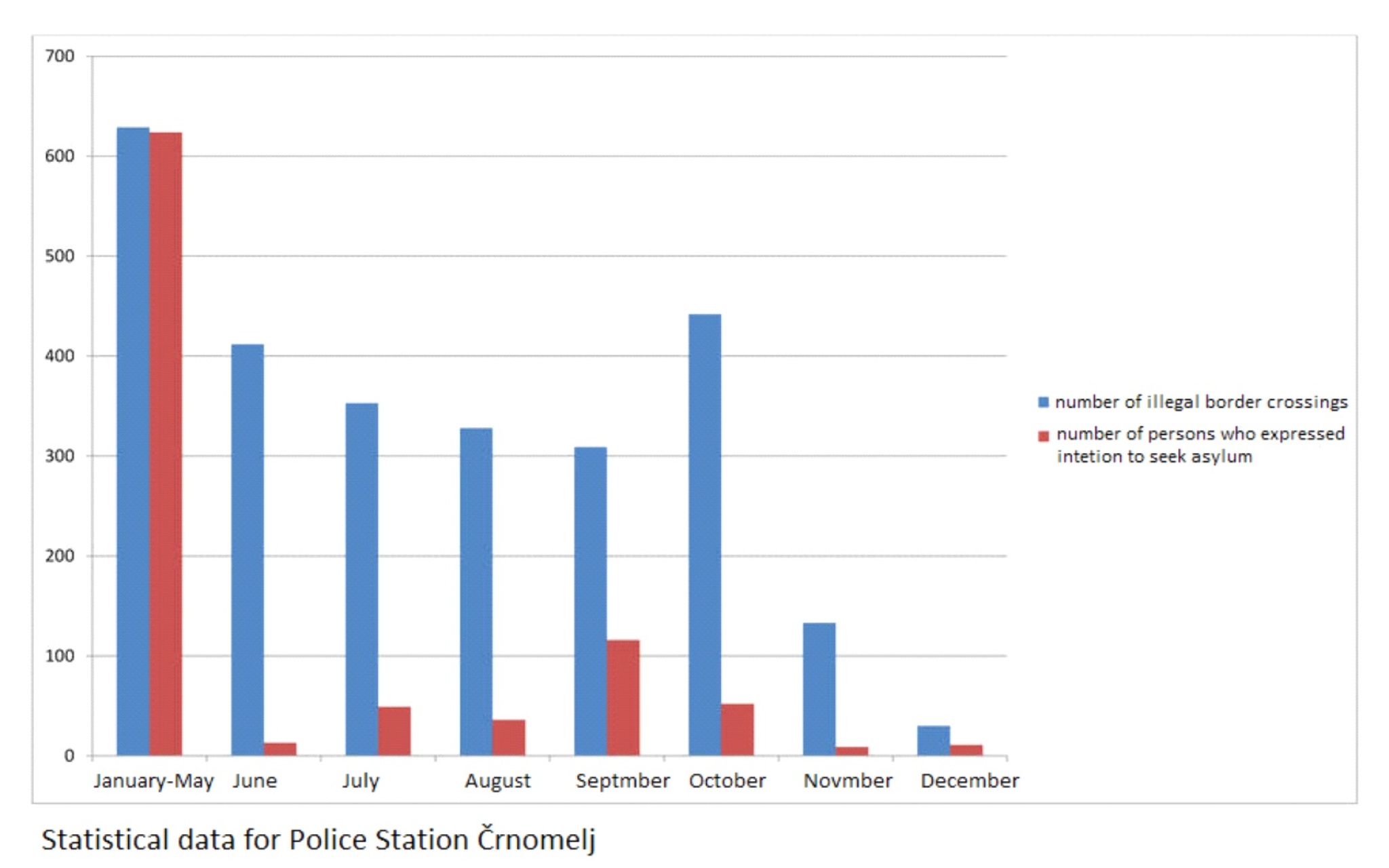

Since the end of May 2018, the Slovenian border police practice a systematic and en masse denial of the right to asylum procedures and collective expulsions known as push-backs. In the same month, on the 25th of May, police stations received an order signed by the former Director General of the Slovenian Police, which instructed that when mixed patrols of Slovenian and Croatian police are present and a person is caught illegally crossing the border, he or she should be returned to Croatia. This order was a malversation of official procedures and a pretext for the systemic practice of illegal expulsions as well as for the use of a readmission agreement between Slovenia and Croatia. The consequences of the order are most evidently mirrored in the example of the Police Station Črnomelj, which operates at the southern border area with Croatia about 70 km away from the Bosnian city of Velika Kladuša from where the majority of migrants along the Balkan route departed towards EU countries in 2018 (see picture 1 for a map of the region). According to a report of the Slovenian Ombudsman of Human Rights in May 2018, the number of persons that were apprehended and processed for illegal border crossings amounted to 379, and 371 of them (98%) expressed the intention to seek asylum at this police station. In June, after police instructions were introduced, 412 persons were apprehended for illegal border crossings, but only 13 of them managed to express intention to seek asylum in Slovenia. This means that from May to June the percentage of people who crossed over to Slovenia and sought asylum with the police in the Črnomelj region dropped overnight from 98% to only 3%.1 The percentage of people whose asylum procedure was accepted only slightly increased in the following months (see picture 2). Those who were denied their right to seek asylum in the official procedures of the police were categorized as economic migrants with no intention to seek asylum and with no right to cross the border to Slovenia, and, thus, were eligible to be processed in accordance with the readmission agreement2. The same practice of systematically denying the right to asylum can also be detected in other police stations along the southern border and even in police stations inside the country. There have been reported cases of chain-push-backs from Italy via Slovenia to Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. In 2018, out of 9149 people who were apprehended for illegally crossing the border to Slovenia, 4653 persons were officially returned to Croatia by the Slovenian police under the readmission agreement. This happened with the full knowledge of the authorities that these people would very likely be then further expelled to Bosnia and Herzegovina, where they faced high risks of being tortured and abused by the Croatian police. According to the official statistics of the Slovenian Police, this even worsened in 2019, which shows increased numbers: 11,026 cases of expulsions.3

According to the testimonies of people who were expelled to Croatia and then to Bosnia and Herzegovina, the procedures at the Slovenian police stations are in many cases accompanied by violence, threats, forcing people to sign documents written in Slovene language without translations, and, in some cases, beatings. When people depart from Bihać or Velika Kladuša, they walk for five to ten days to reach Slovenia, depending on the group and the route they take. During the walk, they usually avoid any contact with the local population in fear of them informing the police, and people often try walking by night in order to remain hidden. Groups usually arrive in Slovenia completely exhausted, without food supplies or water and are, thus, easily caught by Slovenian police. After the arrest, people are brought to the police station, where their belongings (phone, money, etc.) are taken from them, the police officers take their fingerprints and photos of their faces. This is followed by a quick and superficial interview with the help of a translator, usually conducted with one member of the group representative for all who arrived. According to testimonies, some translators are aggressive and biased, and they often interrogate asylum seekers although they are not authorized to do this.4 Subsequently, the police issue a monetary fine of 250-500 euros for the offence of illegal border crossing. Sometimes dry clothes, water, and some food are provided; sometimes people are forced to sleep at the police station or in containers in their wet clothes on the ground, without food or water. After several hours or a day, they are transferred to Croatian police and processed under the readmission agreement. In the process of a readmission, the belongings of migrants are usually handed over to the Croatian police in sealed envelopes rather than to the migrants. Large numbers of envelopes and wristbands that were used during readmissions from Slovenia to Croatia were found in the border area near Bihać, where Croatian police conducts illegal expulsions (Picture 3 and 4).

An especially frustrating matter is the silence and passivity displayed by institutions that are supposed to promote and defend human rights. The Human Rights Ombudsman in Slovenia refuses to confirm allegations of unlawful police conduct despite ever-growing evidence and is, to this day, unwilling to start a thorough investigation, condemn the systematic abuse of human rights, or press for criminal charges against those responsible. On 26th and 27th of September 2018, even a delegation of the UNCHR visited police stations at the Slovenian-Croatian border in Ilirska Bistrica, Črnomelj, and Metlika. The delegation commended the work of the police and did not detect any procedural violations. All of the visits were announced beforehand.

Info Kolpa and Monitoring Police Procedures at the Border

The civil initiative Info Kolpa started with a group of activists and volunteers visiting Velika Kladuša and Bihać in Bosnia and Herzegovina distributing leaflets among people on the move in spring 2018. The leaflets contained information on asylum procedures in Slovenia, including information on the responsible authorities, what their rights and obligations were in different stages of a procedure, what the Dublin regulation is, information on the police’s illegal practice of denying asylum requests, and a list of useful contacts. The leaflet included a telephone number people could call if they wished to seek asylum after crossing the border to Slovenia. The telephone number operated like the principle of the Alarmphone, which has already proven to be somewhat effective in some other parts of Europe (Croatia, Spain, Greece, Italy) in fighting the unlawful practices of police. The purpose of the info phone was to have a third party present during the first step of expressing intention to seek asylum and to independently monitor border crossings and police procedures.

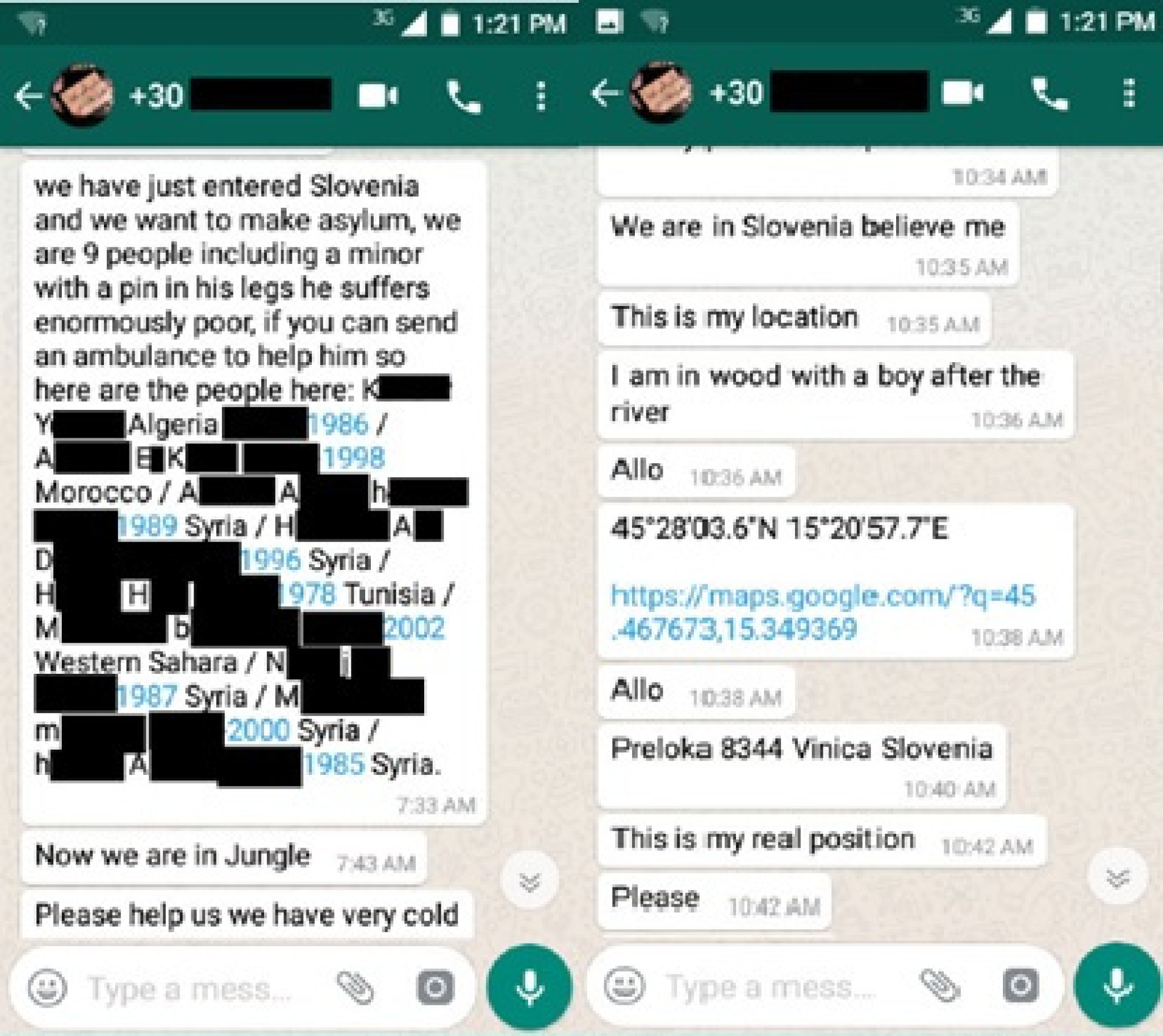

In the beginning, the info phone number was established in cooperation with a legal NGO Pravno-informacijski center PIC (Legal-Informational Centre). The 24-hour telephone line was working with mobile phones and WhatsApp applications, with people taking shifts every two or three days. People mostly called or wrote to the number after crossing the Slovenian-Croatian border. When they themselves wanted to, they also reported their name, age, country of origin, location, and the number of persons in their group. Once they confirmed their wish to apply for international protection and deal with the police, a volunteer would inform the authorities of the location of the person and their intention to seek asylum (example can be seen in pictures 5a, b). Initially, members of PIC were informing police stations via telephone or e-mail about the intention of people to seek asylum in Slovenia. In July and August 2018, 16 interventions were carried out in cases of groups that had declared their intention to apply for asylum in Slovenia. In 13 cases, the police complied with legislation, and people were allowed to start asylum procedures, while in three cases the police claimed that the groups were never located in that area. Later, it turned out that they were pushed back across the border.

On 7th of September 2018, a joint press conference was held by the Ministry of the Interior and the Human Rights Ombudsman in Slovenia. During this press conference, now former interior minister Vesna Györkös Žnidar publicly condemned the activity of an unnamed non-governmental organization that informed police stations about persons wishing to seek help and demanded they be allowed to seek asylum. The minister deemed the demand of the members of the NGO, namely that police officers comply with legislation, was problematic and out of their jurisdiction. It did not take the media long to discover that the unnamed non-governmental organization was PIC. This discovery was followed by a media lynch by the influential newspaper Delo, which even accused the NGO of human trafficking. Members of PIC withdrew from the practice of operating a telephone line because they feared that the existence of their organization was in danger, while a group of activists continued the practice with a different telephone number and under the name Info Kolpa.

Since then, the police was informed with an anonymous email address and messages that were signed with Info Kolpa. Also, a prepaid SIM card was used to operate the phone line. Despite having no institutional backing, the 24-hour phone line remained operational with volunteers taking shifts every few days. The number that was initially distributed via leaflets during visits to Velika Kladuša and Bihać in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) was later shared between migrants themselves. Many people on the move stranded in BiH soon began to contact the number, asking how the number works, what it is about, and requested information on options for seeking asylum in Croatia or Slovenia, or getting different forms of help. The people on the move also sent information and videos from the protest at the border crossing point Maljevac (BiH) to Croatia (EU) in October 2018. In our WhatsApp communication, we initially explained that we could only inform police of their wish to seek asylum in Slovenia once they had crossed the border, and that we could not guarantee they would be accepted to any asylum procedure. Some of the migrants decided to contact us again after they crossed the Slovenian border. Many people only established initial contact with us after they managed to reach Slovenia. We gave them the same explanation, and we shared the information we had on asylum procedures and illegal actions of the police. The procedure itself remained the same as during our cooperation with PIC: if a person wished to seek asylum in Slovenia, he or she could send us his or her name, nationality, age, and location when on Slovenian territory, and, if the person agreed, we would contact the police station in that area. We specifically said that we could not guarantee a person to be accepted to an asylum procedure and taken to a camp in Ljubljana. The issue we faced many times was that migrants considered the number to be the official number of the asylum office in Slovenia and thought calling the number would guarantee them to be taken to an asylum camp. We tried to clearly explain that we were an informal group and could not guarantee that the person would be accepted to any asylum procedure and informed them that the police decide to deny the right to asylum procedures in the majority of cases in which we intervened, stressing that our initiative primarily aimed at putting pressure on the police to follow the law and respect the right to asylum. Language barriers were a major problem because many people who contacted the number did not have sufficient English skills, and we did not have translators present to be fully able to communicate what we could do and what to expect when facing the police.

Between the 11th of September and 7th of November 2018, Info Kolpa intervened 20 times with e-mails or phone calls at police stations. Apart from the police, the presence of people wishing to apply for asylum in Slovenia was also communicated via email to the Ombudsman, Mirovni institut (Peace Institute) in Ljubljana, Amnesty International Slovenia, and other organizations involved in protecting human rights. These 20 cases (106 persons) were recorded in a full report which was presented at a press conference in Ljubljana in May 20195. In six cases, persons were admitted to the asylum procedure in Slovenia (27 persons); in seven cases they were readmitted to Croatia and then expelled to Bosnia and Herzegovina (39 persons); only one person was able to initiate a procedure for international protection after an extradition to Croatia and not being expelled to Bosnia and Herzegovina. In seven cases (39 people) there is no information on what happened to the people, as there has not been any contact since Slovenian police apprehended them. In the case of the latter, it is possible that the people did not want any further communication, the police officers seized their phones for the purpose of an investigation, or the phones were destroyed or stolen either by Slovenian or Croatian police.

Towards the end of 2018, the phone communication had died down. It became apparent that the police insistently practiced systematic rejections and expulsions of asylum seekers, despite being made aware of people’s intentions to apply for asylum in Slovenia. The situation was not improving even though state institutions and NGOs dealing with human rights protection had been informed about the police’s actions. Hence, the telephone number was no longer serving its original purpose of helping people in need and intervening against the illegal and unethical police practice.

Conclusion

Info Kolpa’s attempt to change the police practice of massively denying people their right to asylum and performing collective expulsions by bringing these practices to public attention has rather failed. It has become clear that neither the government nor any other state institution is willing to condemn or even thoroughly investigate the actions of police at the border despite clear evidence of unlawful acts by the police against thousands of people traveling along the Balkan route. The initiative was more successful as a source of information on how push-backs are happening in Slovenia, and it offered insight into police procedures dealing with migrants at the border. When it comes to the intention of the initiative to provide support in concrete situations, one can conclude that the police predominantly ignored interventions coming from an anonymous and informal group such as Info Kolpa. The practice of offering direct support via an info phone was much more successful when interventions were made by a lawyer of an NGO (PIC) already involved in the official oversight of protecting human rights in state institutions. Such a status provided the organization some leverage when making calls to the police stations, but it was also a source of vulnerability. As legal NGO providing free legal assistance to asylum seekers in Slovenia on asylum procedures, PIC depended on public funding provided by the Ministry of Interior Affairs and could, therefore, easily be disciplined. The grass-roots initiative offered a possibility for a stronger and more radical condemnation of police violence by the Slovenian state, which was realized with a public press conference and an event in which we presented our findings in a form of a report that provided proof of illegal police actions to the public as well as with offering a space for migrants to share their experience of police abuse. The Slovenian police increased its presence and repression at the border in the last year. Directly challenging border violence is something that goes beyond the abilities of small groups of likeminded people who do not agree with systemic violence of the state against migrants. Although the Info Kolpa phone was extinguished, the group has continued its activities: It has regular meetings with refugees and asylum seekers in Ljubljana, monitors the situation in refugee camps or at the border with Croatia and in BiH, where migrants are stranded, organizing petitions, denouncing further militarizations of the border, and are looking for ways to effectively oppose police and state violence against people on the move.

Varuh človekovih pravic (2019): Končno poročilo o delu policije na meji s Hrvaško. URL: varuh-rs.si [01.02.2020].↩︎

Državni zbor RS (2005): Zakon o ratifikaciji sporazuma med Vlado Republike Slovenije in Vlado Republike Hrvaške o izročitvi in prevzemu oseb, katerih vstop ali prebivanje je nezakonito (BHRIPO). URL: www2.gov.si. [01.02.2020].↩︎

Policija (2019): Ilegalne migracije na območju Republike Slovenije. URL: policija.si [01.02.2020].↩︎

Videmšek, Boštjan / Emrić, Nerminka / Povše Matej (2019): ›Go back to where you came from‹. URL: ostro.si [01.02.2020].↩︎