Abstract This contribution explores the EU strategy of containment in Serbia trough critical mapping, analysing the construction of camp facilities after the closure of the Balkan corridor. It consists of a series of maps of camps built in Serbia in the last years, developed by the author. From 2015 to 2017, the state of Serbia has rehabilitated, refurbished, and built new camp facilities using European funds. Following a European strategy of containing and impeding migration movements from south to north, Serbia has kept thousands of people outside of the western EU territory. Whether under the label of transit, reception, or asylum centres, camps have pushed, held, and left thousands of people on the move hopeless, without clear future alternatives, living in legal and humanitarian limbos for years. These maps critically present how these infrastructures serve an EU strategy of containment and deterrence, redrawing the geography of migration in the region. Using official and available data, this work shows infrastructures, numbers of people, and funds. It focuses on a time frame beginning from the closure of the Balkan corridor to the present time. Within few years, the once open Balkan corridor across the former territory of Yugoslavia became a field to experiment the EU strategies of containment.

Keywords Serbia, Balkan route, EU, containment, camps

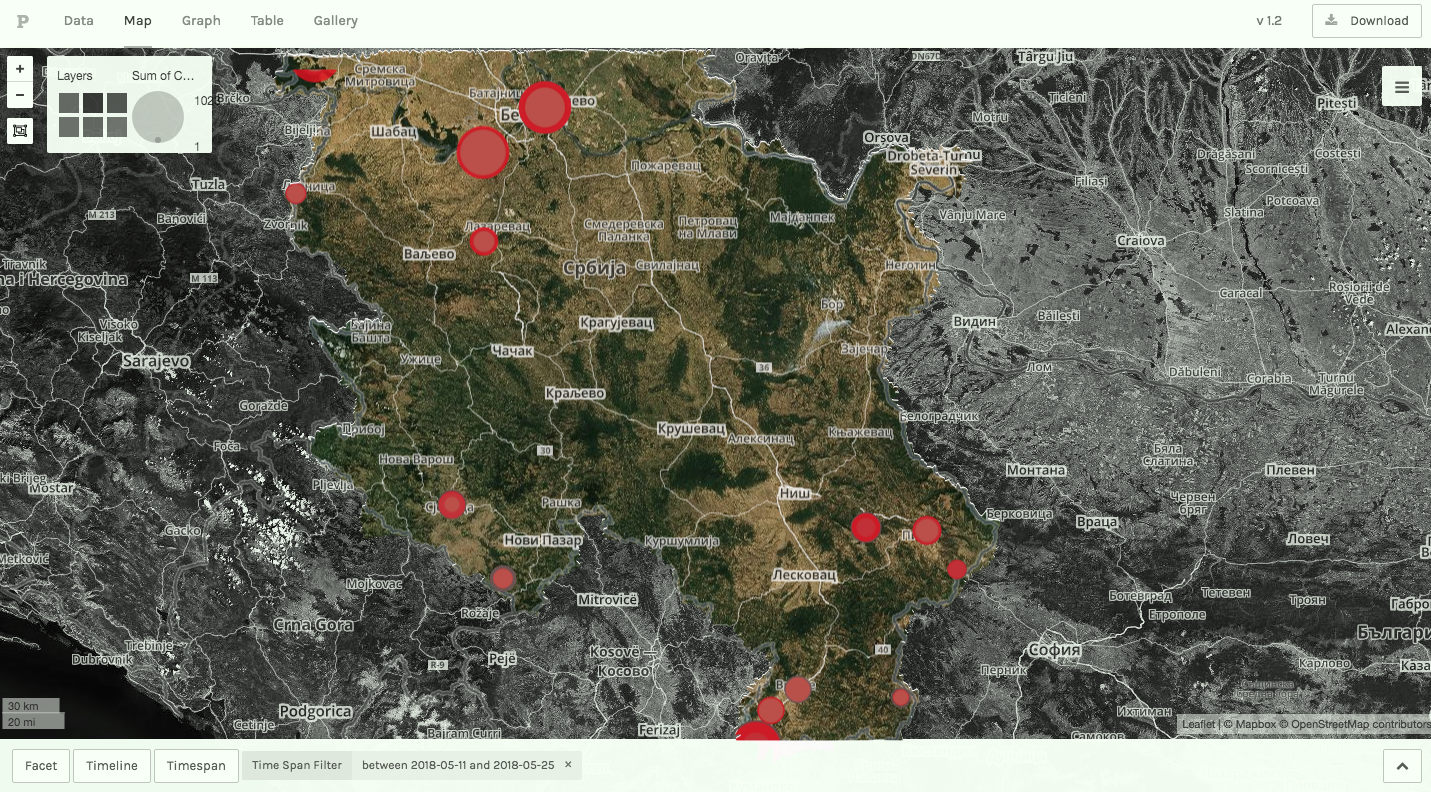

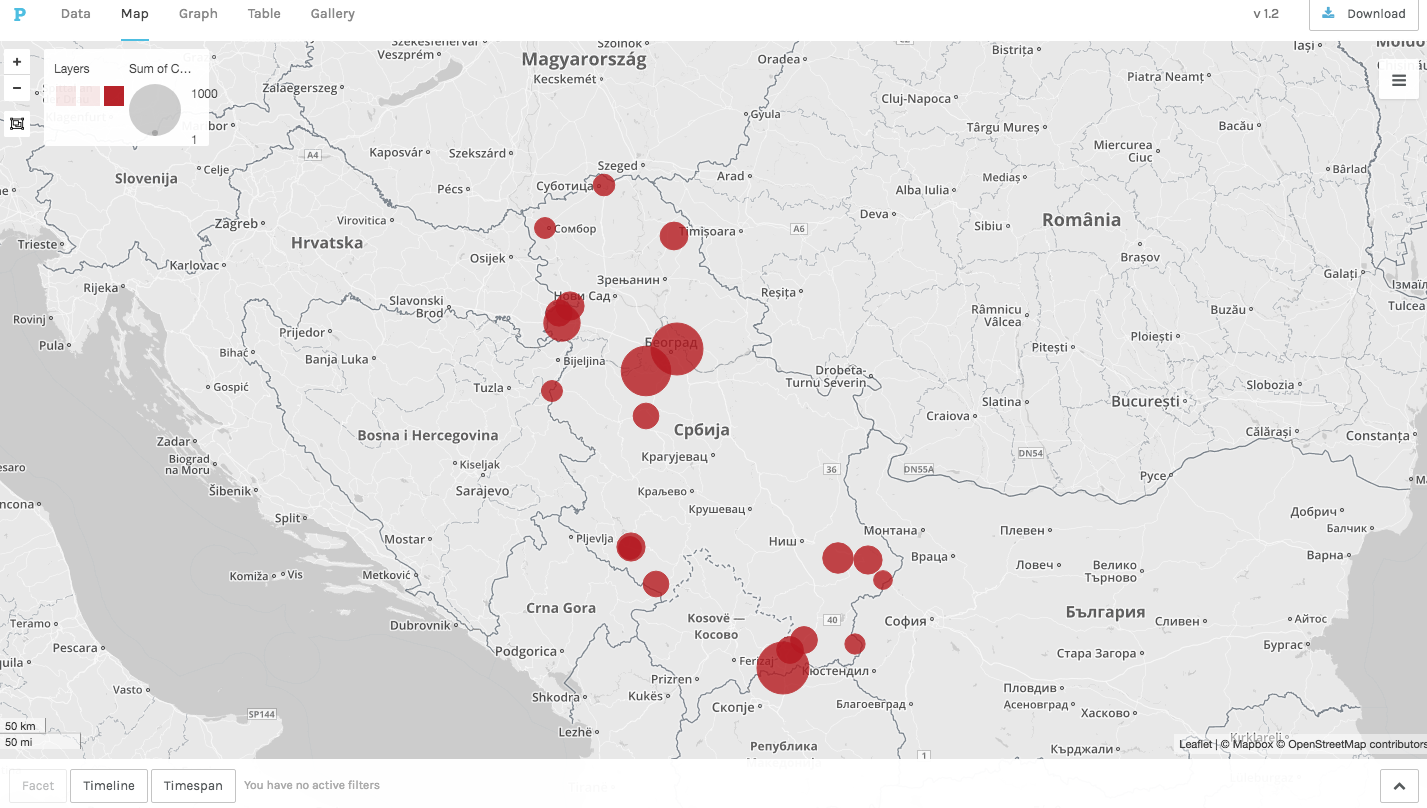

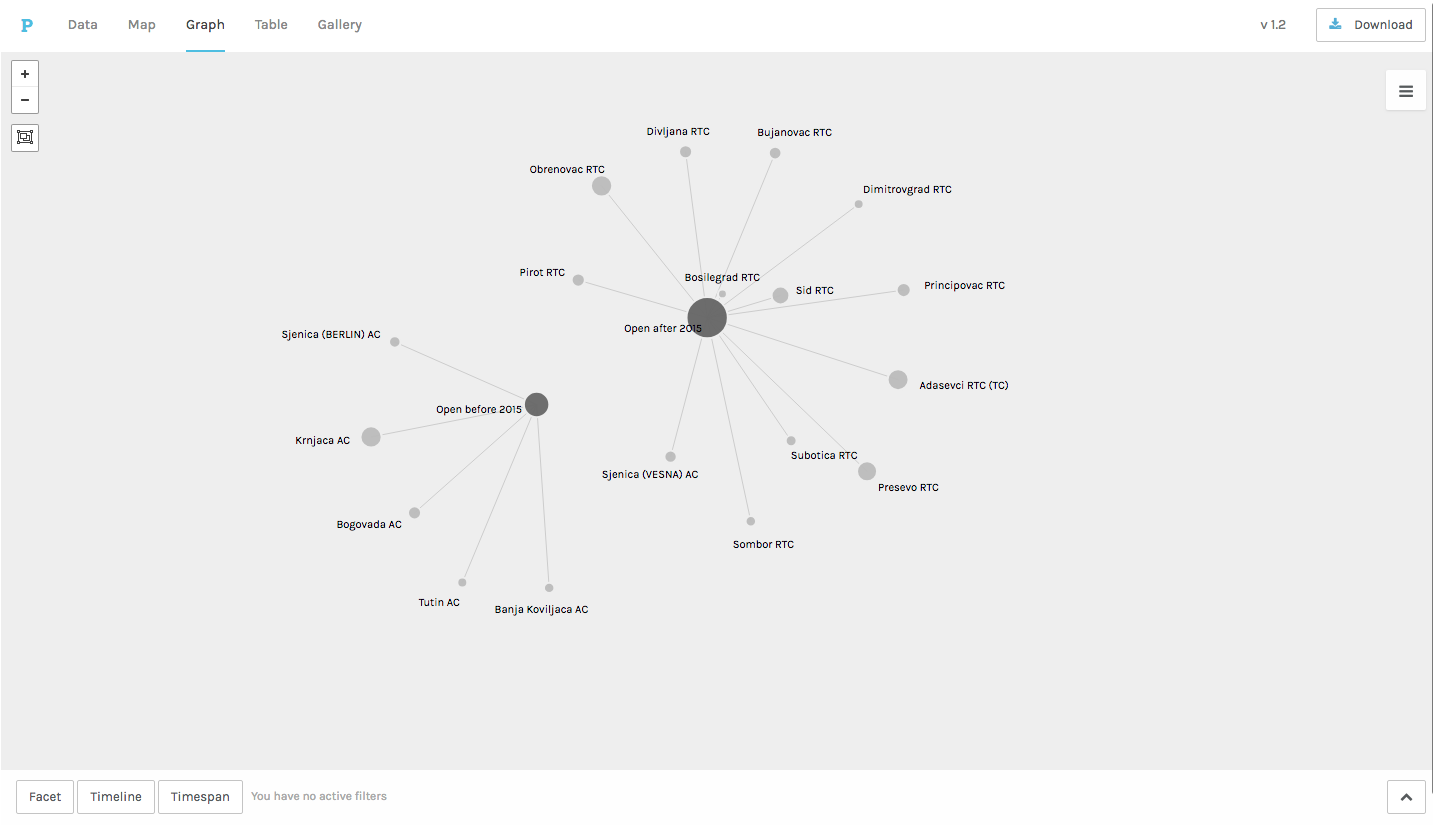

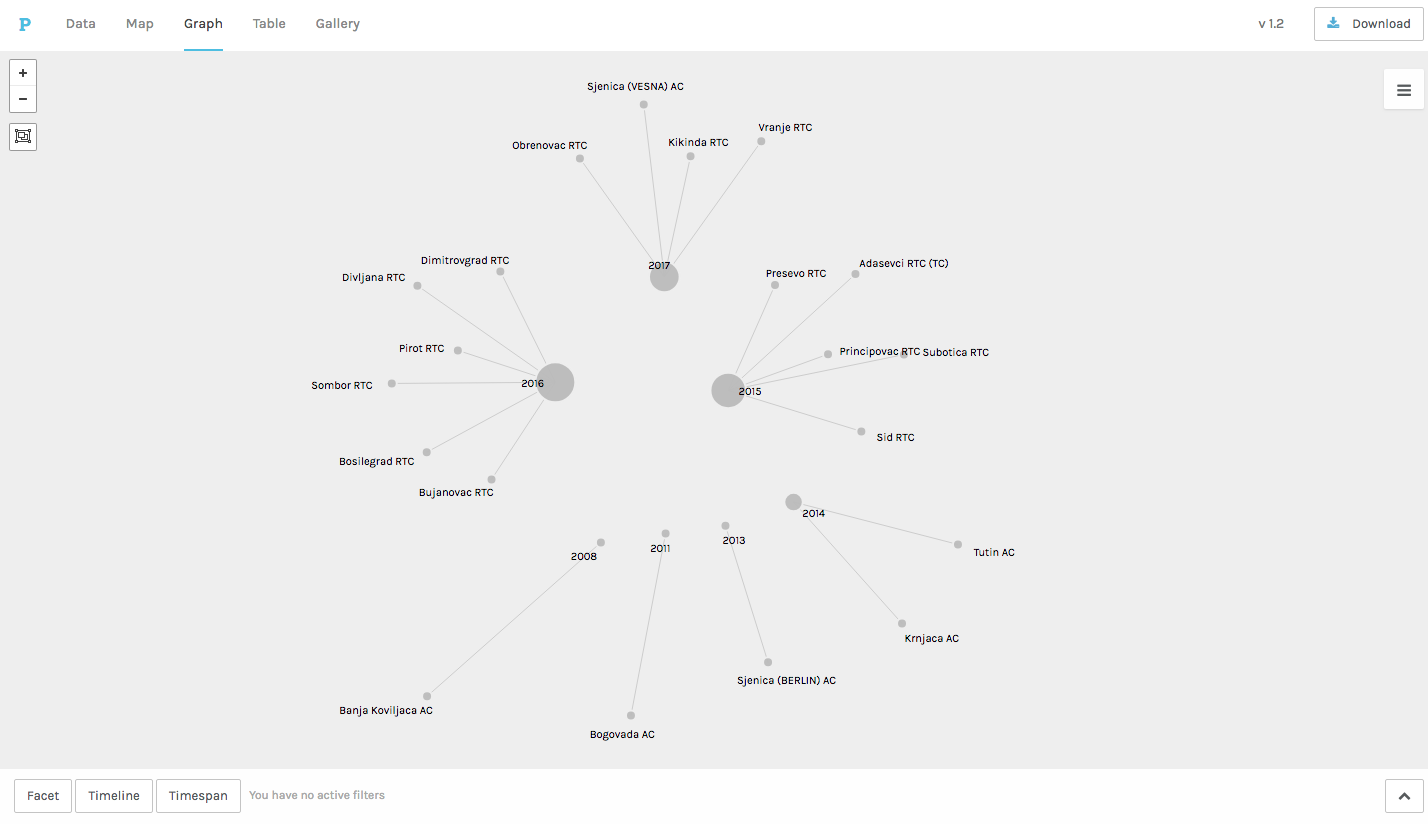

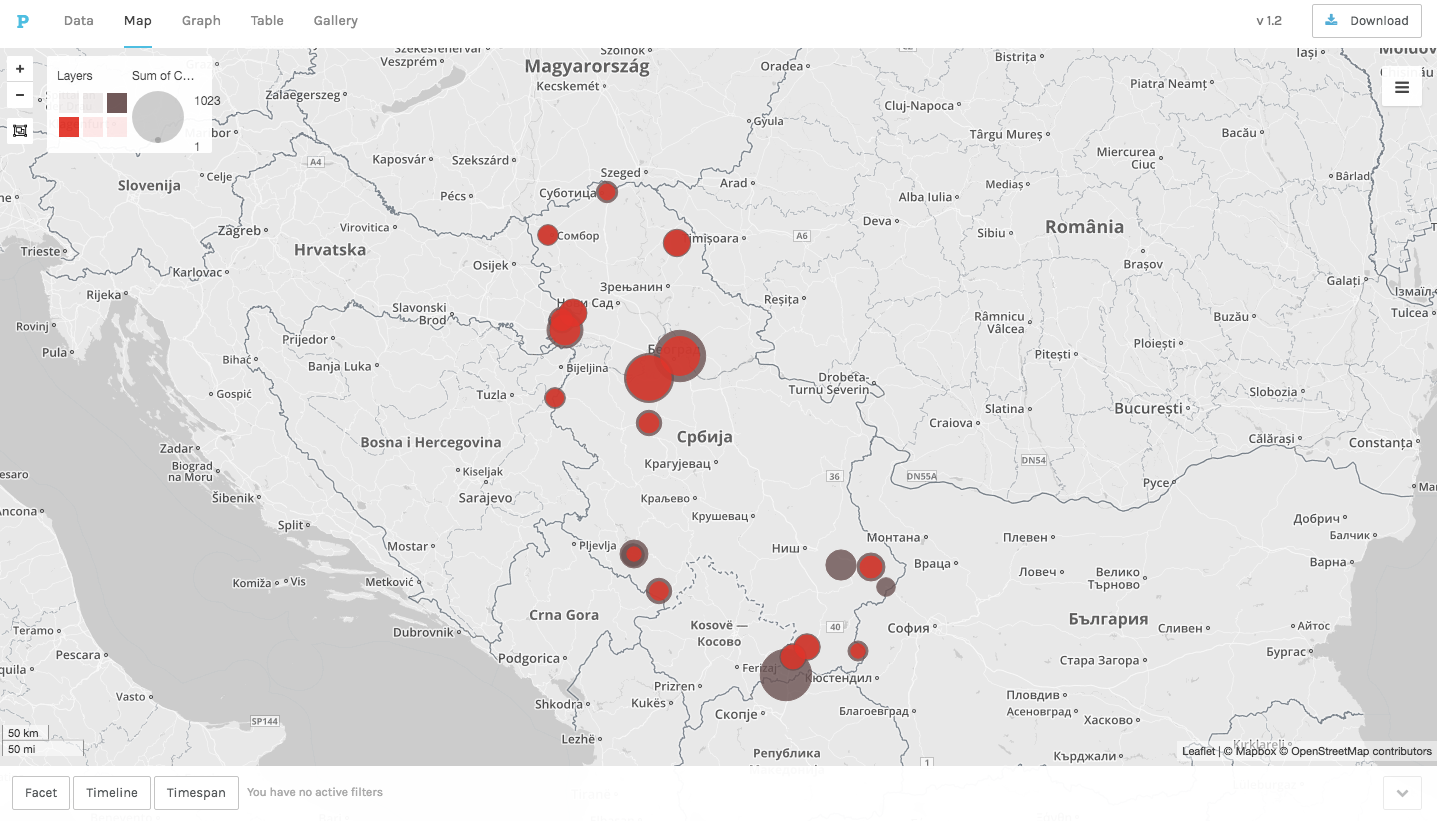

This series of maps covers the construction of asylum and reception facilities in Serbia from 2008 to 2019. The maps critically analyse the period between 2015 and 2017. During these two years, the government of Serbia rehabilitated, refurbished and built new camps to respond to the increasing south to north migration movements across the Balkans, thereby serving an EU strategy of containment and deterrence redrawing the geography of migration in the region.

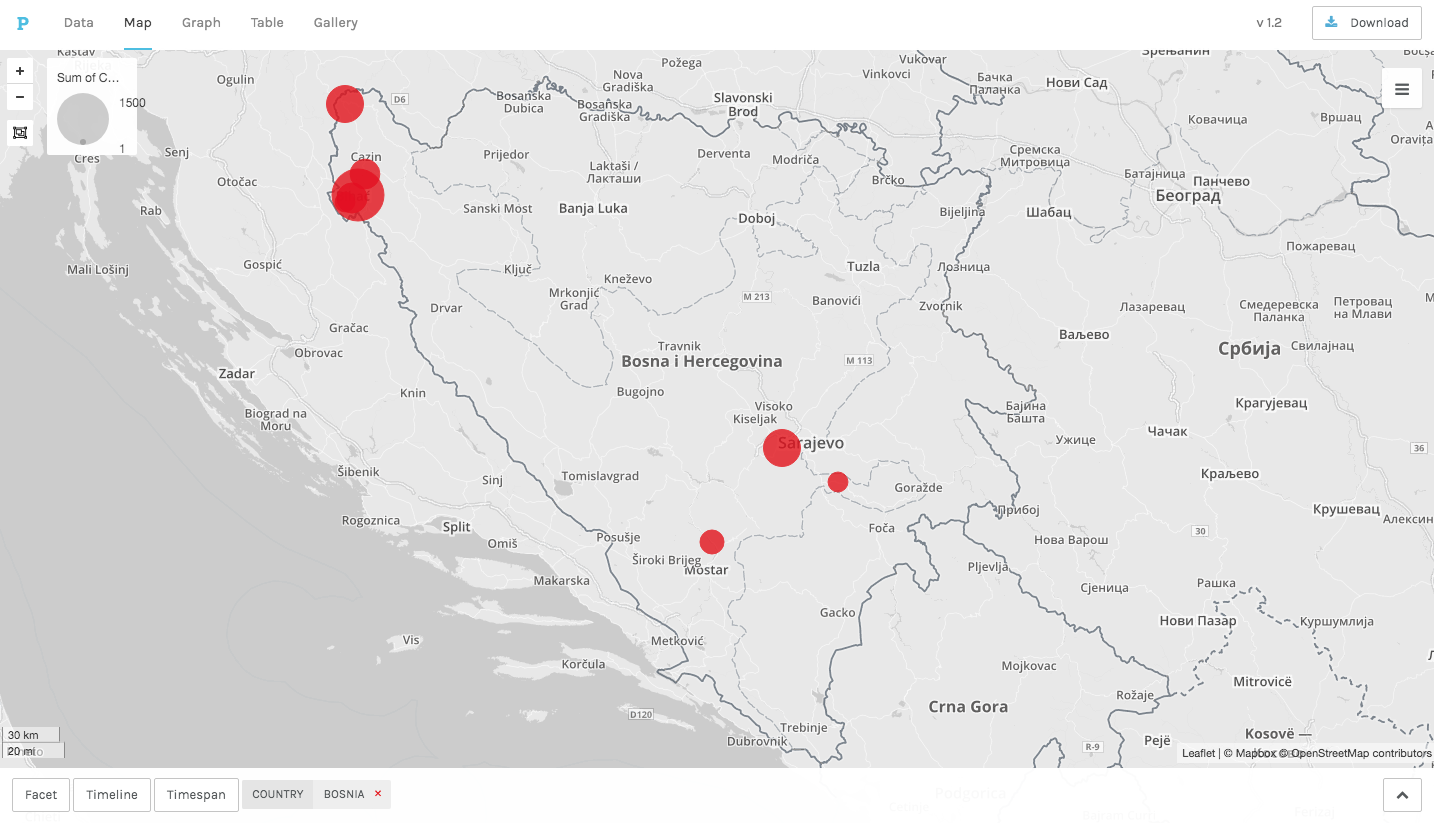

Since 2015, under the supervision of EU authorities, UN agencies, and non-governmental organisations, the Serbian government has received more than 130 million euros by the EU to »secure its borders« by managing and establishing new and existing camps. These facilities aim at hosting people on the move crossing the country. However, under the label of asylum, transit or reception centres, camps keep and leave thousands of people in inhumane and degrading conditions. Such infrastructures serve a regional strategy of containment (see Beznec/Speer/Stojić Mitrović 2016; Hameršak/Bužinkić 2018), oriented towards controlling movement, sustaining a politics of fear (see Wodak 2015), keeping the ›unwanted‹ outside of the EU borders. The maps highlight the years 2017, 2018 and 2019, when thousands of people were confined and left without any choice than accepting inhumane and degrading living conditions in Serbia. From 2018 onwards, migration routes started to shift towards Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) (see UN 2018, 2019). A video included in the online version of this series of maps reveals how from 2018 to 2019, following the migration movements, new camps were erected in BiH.

The mapping project—both maps and graphs—has been realised using Palladio, a software developed by Stanford University for the visualisation of complex historical data. Based on official and unofficial data,1 such as interviews with different actors, fieldwork, and relevant literature, the maps present mainly the number of people and infrastructural capacities from 2017, 2018 and the first six months of 2019 (see UNHCR 2017; 2018; 2019), including snapshot analyses of south to north movement limitations, main donors, and organisations involved. This work does not want to give an objective account of what has happened in the Balkans in the last years. On the contrary, it aims at reporting a subjective analysis of three years of observations, discussions, and struggles shared and spent in the region. A more comprehensive study including informal settlements and a better visual analysis of movements in Serbia and other neighbouring eastern European countries is yet to be done. The dataset used to create the maps is attached to this work and can positively encourage a wider network of collaborations on the subject of containment in the region and, hopefully, beyond.

This mapping attempt is limited to displaying the constantly shifting geographies of migration of the last decade in which the Balkans became the field of experimenting new and old strategies of containment and deterrence. Nonetheless people are still moving, and their presence at border areas reminds all of us of their struggles (see Mezzadra/Neilson 2013).

From 2008 to 2019—Building Containments

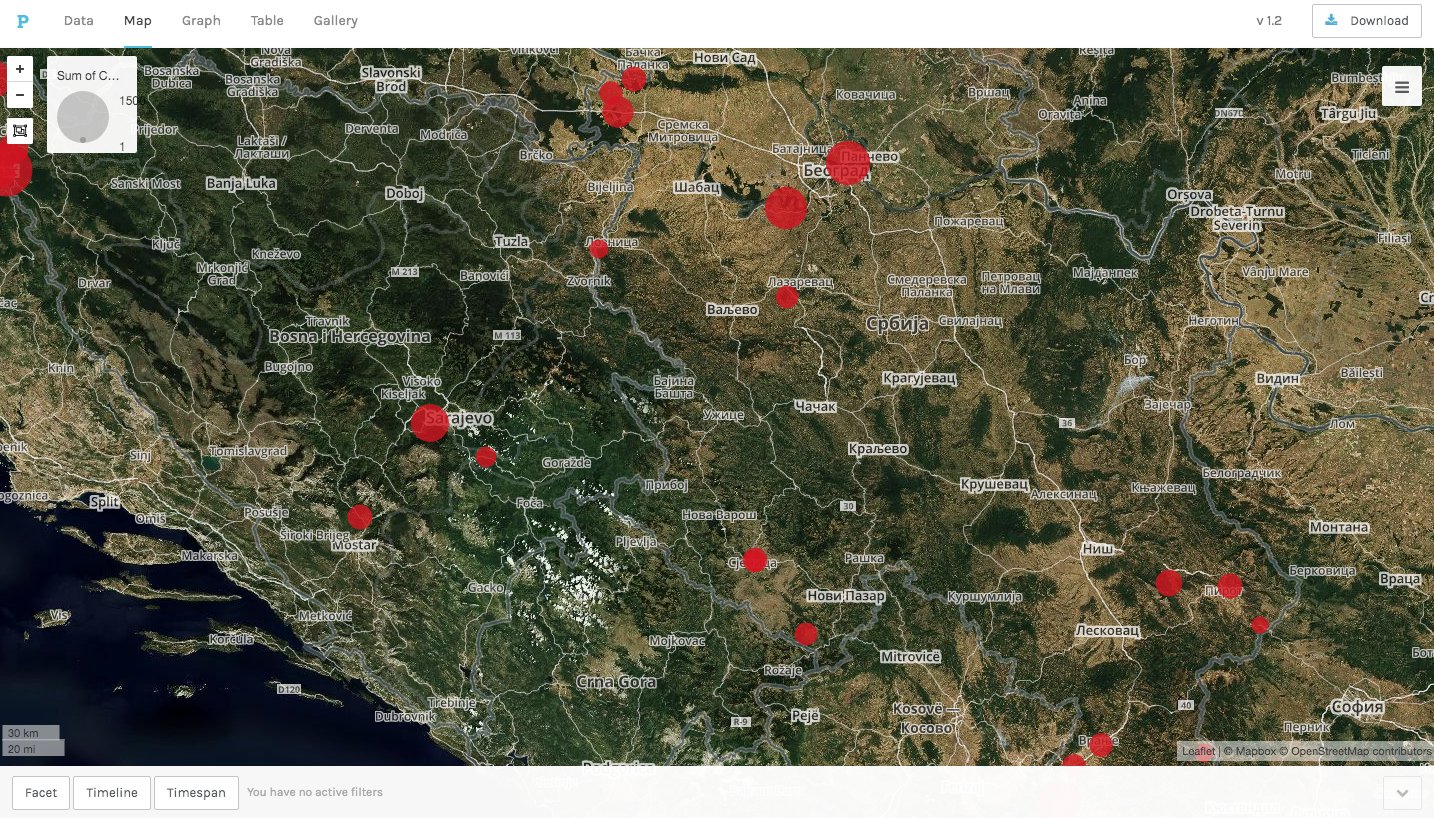

From 2008 to 2019, both Serbia and BiH have served as extra-EU territories to contain most of the south to north movements reaching the western EU. The video shows the timeline of the construction of camps whereby the size of the dots represents their maximum capacity up to date.

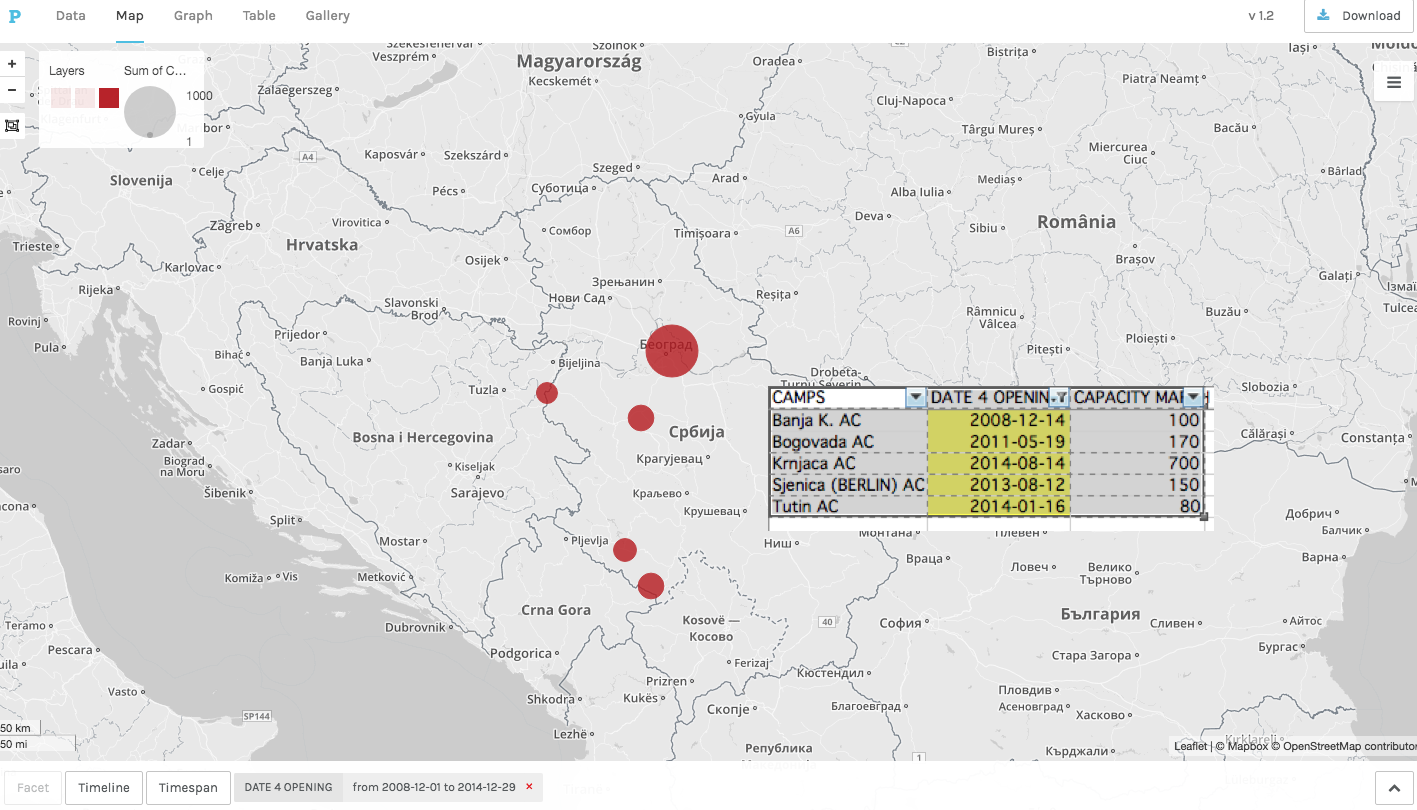

From 2008 to 2014, Serbia opened five camps under the official name asylum centre (AC). New and old patterns of forced displacements match and overlap in the same locations. Serbia has a long-standing experience with refugees and the protection of displaced populations. In 1996, at the peak of the post-Yugoslav war, Serbia accommodated more than 530,000 refugees from Croatia and BIH as well as 700,000 displaced people from Kosovo while the number of camps was around 700 (Komesarijat 2008: 2). When the new refugees reached Krnjača AC in Belgrade, the old families from the Yugoslav wars were still there. Similarly, Salakovac camp in BiH used to be for people displaced during the war, and it was recently rehabilitated for people crossing the Balkans (see Boitiaux 2018).

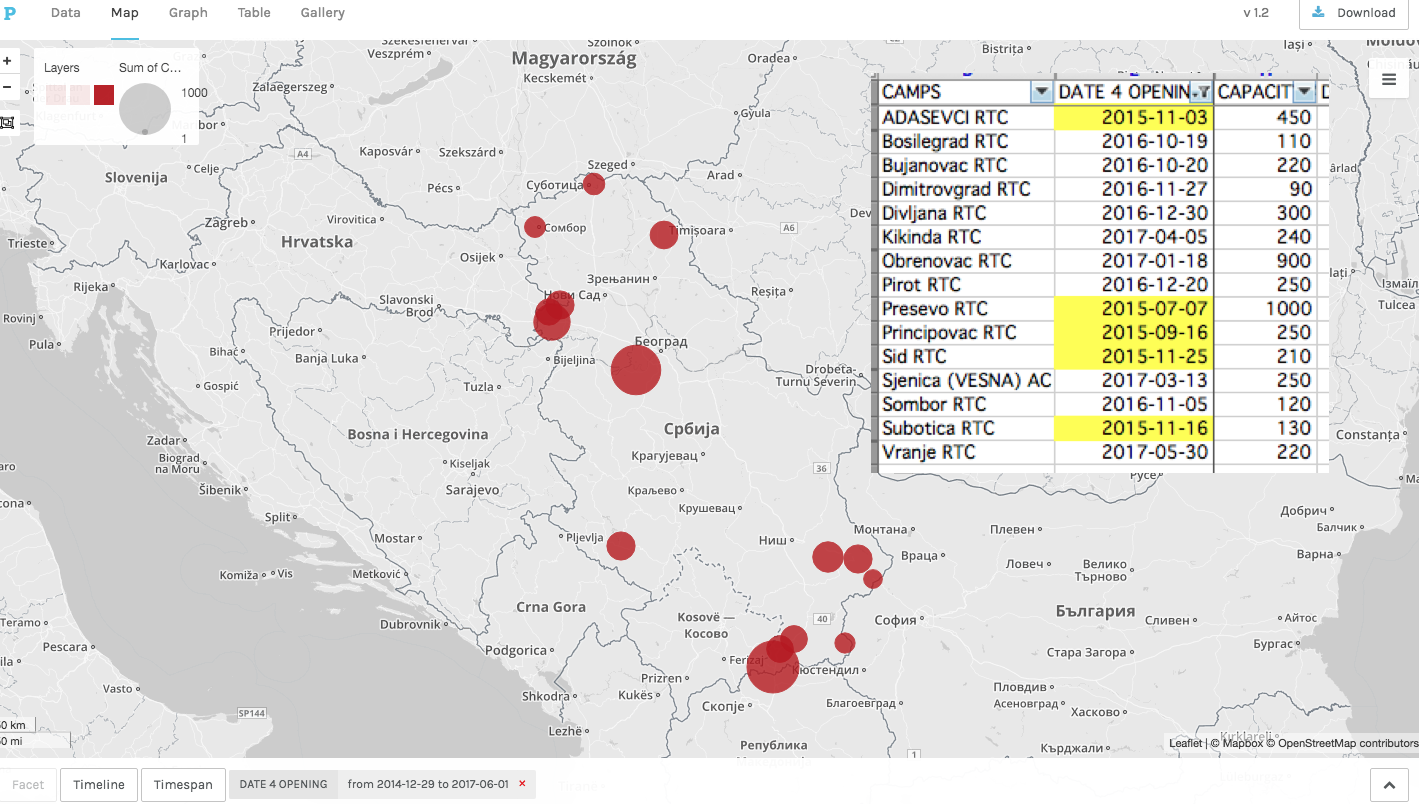

From 2015 to 2017, Serbia set up 15 camps with only one in Sjenica labelled as asylum centre. Under the name of transit and reception centres, those facilities where mainly built with funds coming from the EU. The European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations (ECHO) has disbursed millions of euros to international organisations, including the International Organisation for Migration (IOM), UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Danish Refugee Council (DRC), and Oxfam to boost the national response to the so-called migration crisis. As part of the countries outside the EU, since 2016, Serbia has benefitted from the EU Trust Fund for Syria known as MADAD. From 2015 to the end of 2017, the EU has funded migration related activities in Serbia for a total of 130 million euros (see EC 2015; ECHO 2018). In the time span of two years, the government of Serbia tripled the number of camps in its territory. In many cases, these infrastructures did not comply with the minimum standards stated in the asylum and reception regulations (see Pravilnik 2008). Despite being part of the accommodation system, those infrastructures remained out of the legal framework up to the introduction of the new Asylum law in 2018 (see ECRE 2018) when the reception and transit centres were included as formal accommodations. However, such changes did not necessarily translate into improving living conditions, which, especially in the northern camps, remained below common standards giving the officials in charge of these centres the opportunity to act arbitrarily at the expense of thousands of people living inside. In the southern camps, standards were aligned to EASO guidelines (2016) offering better living conditions. In addition, the proximity to Bulgaria and the North Macedonian borders fostered a number of expulsions. Under the supervision of the EU, Serbian authorities and NGOs prioritised to improve the living conditions in the camps in the south rather than those in the north in order to dissuade south to north movements within the country, thereby facilitating geographical containment.2

In 2019, besides the six asylum centres, there are 14 so-called prihvatni and tranzitni reception and transit centres. With the approval of the new Asylum Law in 2018, »hotels, resorts, other suitable facilities« (Article 50) were finally included in the legal framework. This should have given access to asylum to thousands of people on the move that for years were left without fundamental rights; however, many are still waiting for recognition of their status. The new asylum law is based on the Action Plan of Chapter 24 of the EU Acquis Justice, Freedom and Security that Serbia has agreed on in order to enter the EU (see EC 2019).

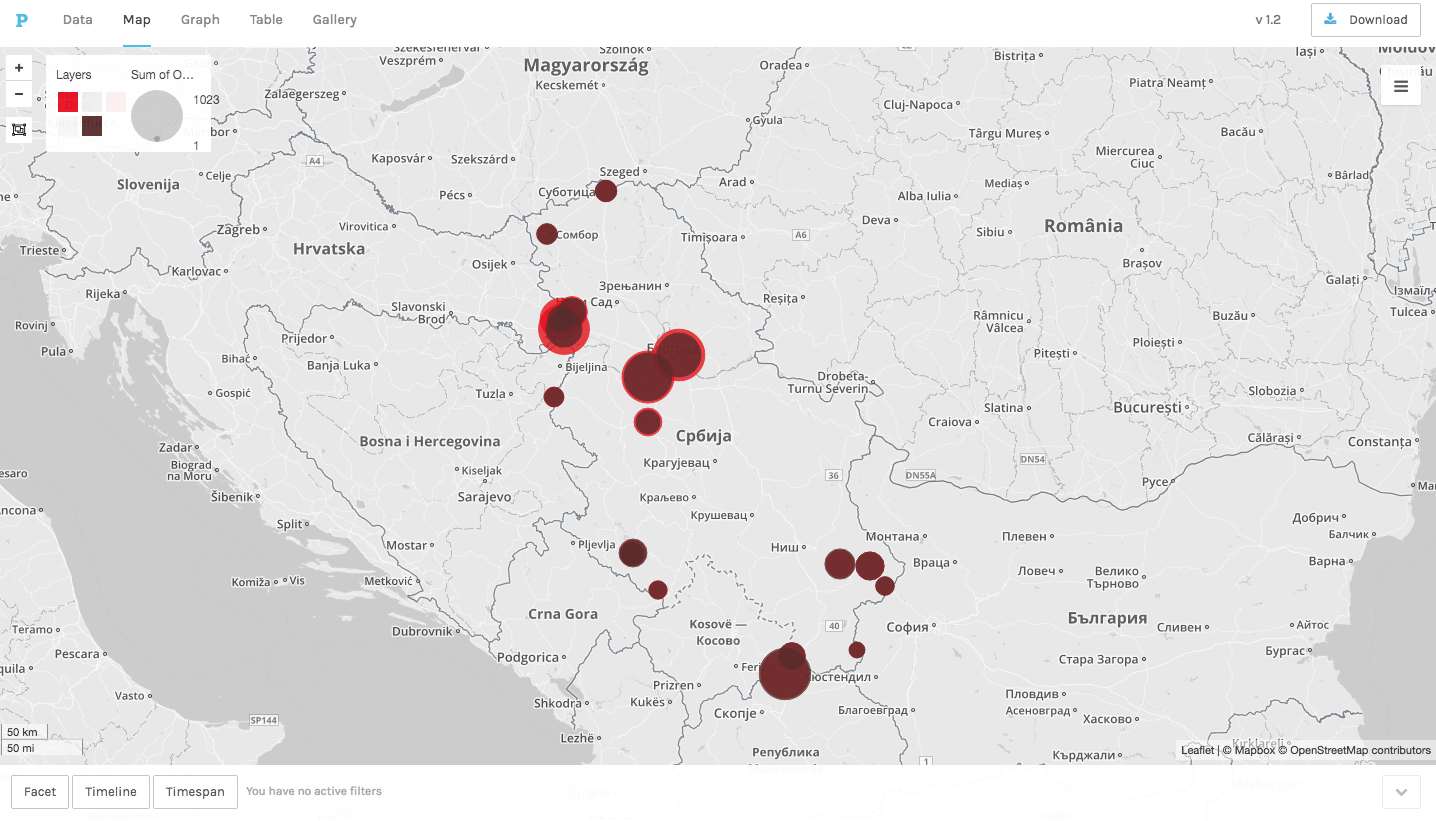

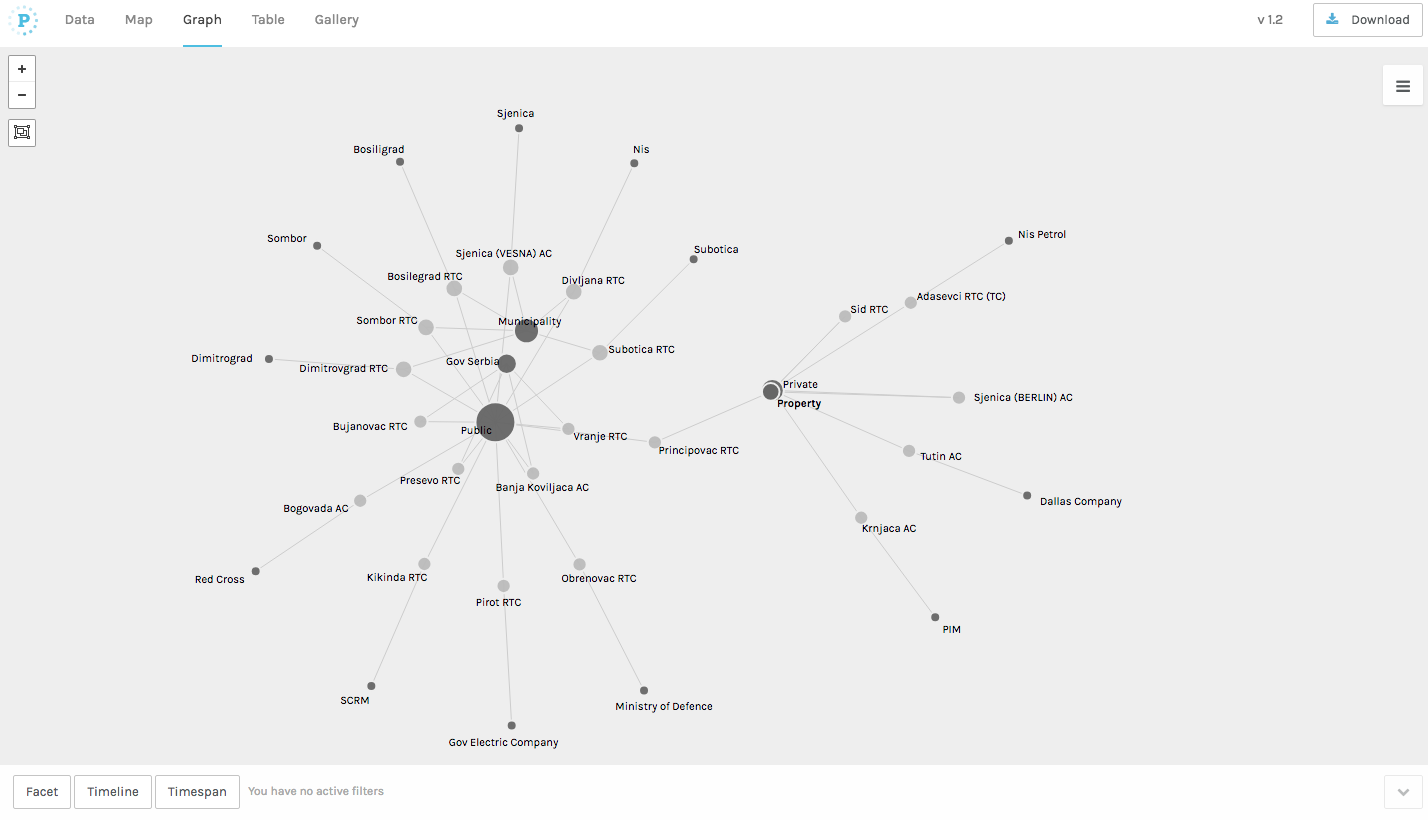

In 2018, the EU allocated a total of 54 million euros to Serbia:3 28 million for border management (see EEAS 2018) and 16 million for responding to the needs of migrants and refugees (see Ministarstvo s.a.) with additional 3.5 million euros spent for food inside the camps.4 Such funds were allocated to Serbia, as it was often stressed at meetings with EU officials, as a reward for what has been labelled as ›good management‹ of migration movements. The sizes of the nodes in the map represent the camp’s capacity.

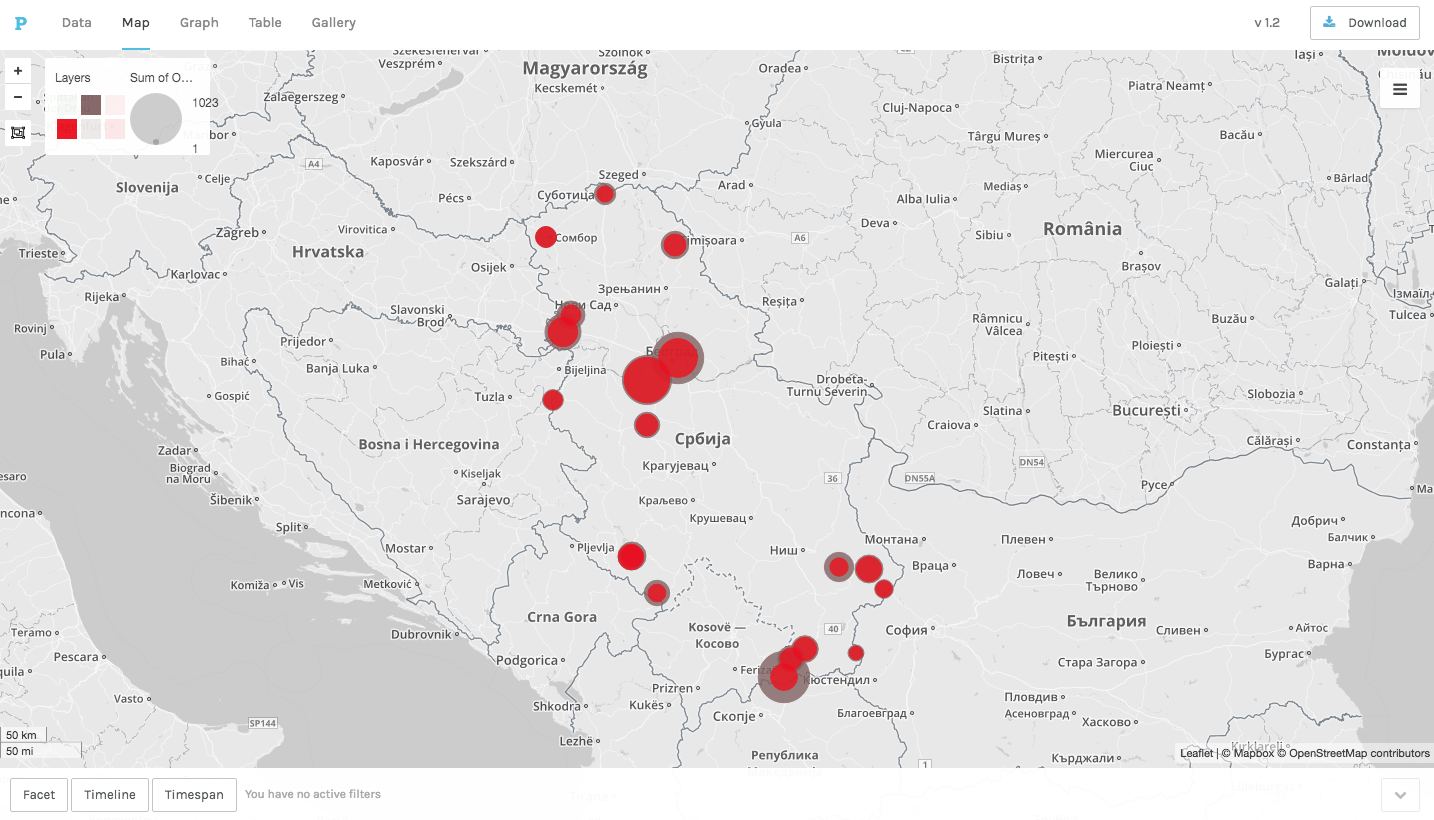

Occupancy vs. Capacity 2017/2018/2019

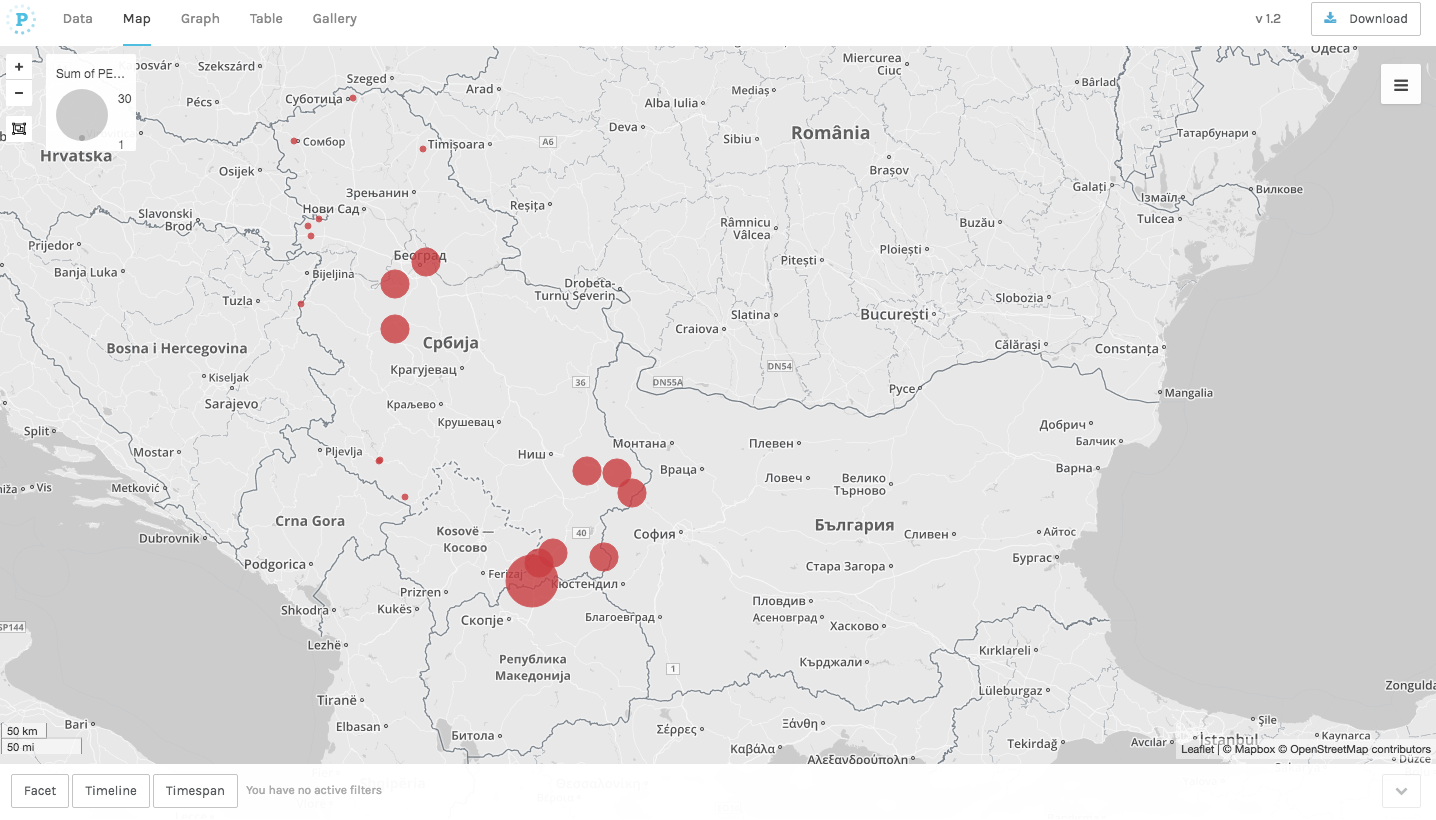

The following four maps show the ratio between the capacity of camps (grey) and their actual occupancy (red) within the years of 2017, 2018 and 2019 (see EEAS 2018). The sizes of the dots represent the number of people. It is clear that all the camps present in Serbia were overcrowded in 2017.

At the end of 2016, an unexpectedly rigid winter trapped thousands of people living in temperatures reaching minus 17° Celsius. In March 2017, the official total number of people stranded in the country reached 6,714 in a space made for 5,380. It is difficult to give an answer to the reliability of these figures. However, adding the almost 2,000 people living in informal settlements, such as the barracks of central Belgrade, the abandoned factory in Sid and several spots between Subotica, Sombor and Kikinda, approximately 10,000 people were present in Serbia at the end of winter 2016/17. The images of the barracks in central Belgrade reached international media round the world, as they showed Second World War-like queues with hundreds of people waiting for a meal under a heavy snow (see Dinham 2017). The camps around Belgrade and towards the Croatian border became worryingly overcrowded, leaving families, children, and many young people in unhealthy and degrading living environments for months. Despite the international pressure, only few international organisations were able to respond, and many solidarity initiatives were conducted by individuals and self-organised actors (Cantat 2020).

At the beginning of 2018, the numbers of people in camps sunk back to the figures of the pre-2015-period: officially, 3,566 people were present in the camps in March (see UNHCR 2017). This has been the result of shifts in the paths of migration towards BiH. From the end of 2017 onwards, people mostly stuck in the North of Greece and Serbia started to cross into BiH in order to reach the Croatian EU borders. After years of brutal systematic violence conducted by the Bulgarian, Romanian, Hungarian, Croatian, and Serbian border police, movements from Greece also diverted towards the route from Albania over Montenegro and BiH to Croatia, or alternatively via North Macedonia, Kosovo, Serbia and BiH to Croatia, or a combinations of the two. These old renewed paths show how, despite years of physical, psychological, and infrastructural deterrence methods, new geographies are still possible in order to confront and challenge restrictive border regimes. However, this remains at the expenses of many people and lives lost that do not even appear in any official statistics. The six-year-old Madina Hussiny who died at the end of 2017 at the border between Croatia and Serbia is a terrible example of the hundreds lives lost crossing the Balkans (see Graham-Harrison 2017). It is unclear how many people died. Taken together, other colleagues and the author counted at least 622 persons between 2016 and April 2018 who lost their lives on their paths from the Turkish shore to the Serbian, Croatian and Hungarian borders.

In May 2019, the presence of people on the move in Serbia decreased to 3,060 (see UNHCR 2019) while reaching from 6,000 to 6,500 people in BiH (see UNDP 2019). In 2018, facility structures started to mushroom all over the country, particularly in its north-western part at the border to Croatia (see Ahmetašević/Mlinarević 2019). Some of these structures could be described as mostly informal, makeshift camps and some (shown on the map) are official camps managed by international organisations. The former territory of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia became a »dumping zone« (see MacDowal 2017) with new spaces of exception of the western rules of law in which EU standards did not apply but whose effects are still visible with the scabies scars, bruises, fractures and cuts on the bodies of thousands of people moving south to north. This has not only revealed the decadence of EU institutions, but also the acceptance and legitimacy of a system of exclusion. In some of the newly revised European asylum and border management laws push-backs are legalised and people who migrate and those helping them are often criminalised.

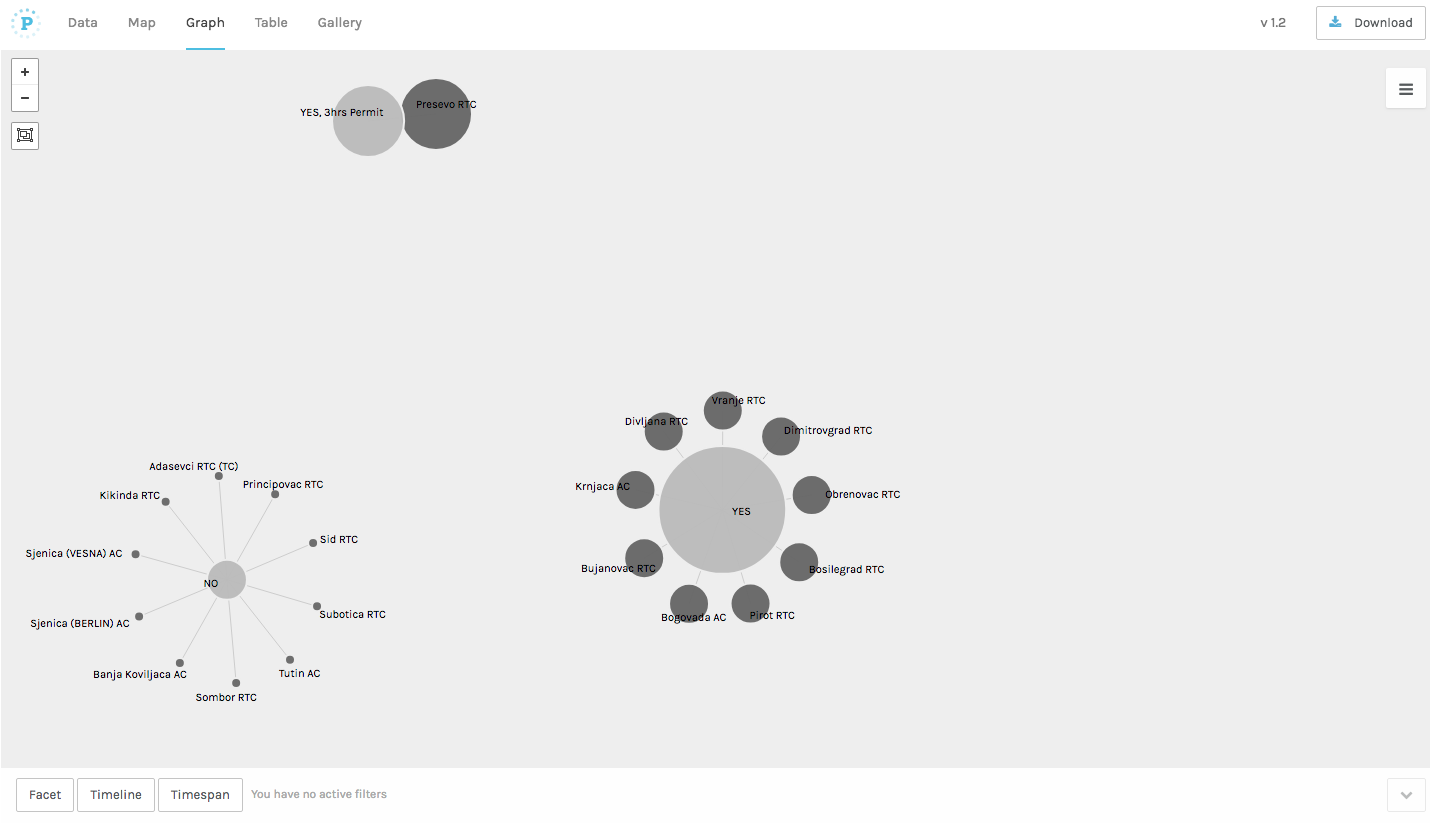

Freedom vs. Restriction of Movement

Following a strategy of deterrence and of discouraging any movements heading northwards, the southern camps showed a stricter form of regulation concerning in- and outward movement. In the north, the so-called transit centres towards Romania, Hungary and Croatia were mostly left without regular maintenance leaving thousands of people in unhealthy living conditions, often without proper care, in which simple parasite, such as scabies and body lice, became chronic. In addition, until 2018, migration movements south to north were controlled by unofficial practices, which consisted in regular arrests at the northern borders, forced relocation to the southern camps, mainly Preševo, and unlawful expulsions to Bulgaria and North Macedonia (see Belgrade Centre for Human Rights/Macedonian Young Lawyers Association/Oxfam 2017; Medecins Sans Frontiers s.a.). In the town of Preševo, unofficial agreements with local officers at the bus station prevented people to board busses going back towards north. Despite many international organisations that were aware of these accounts, it was difficult to prove. As a consequence, several people in Preševo started to ask to be »voluntarily deported« to North Macedonia. It has been mentioned that the only way to move north was to go back to North Macedonia and re-pay smugglers in order to cross back into Serbia, thereby overcoming Preševo area, to reach Belgrade. It is important to underline that such unlawful expulsions were conducted without respecting any readmission agreement leaving several people completely unattended at the border.

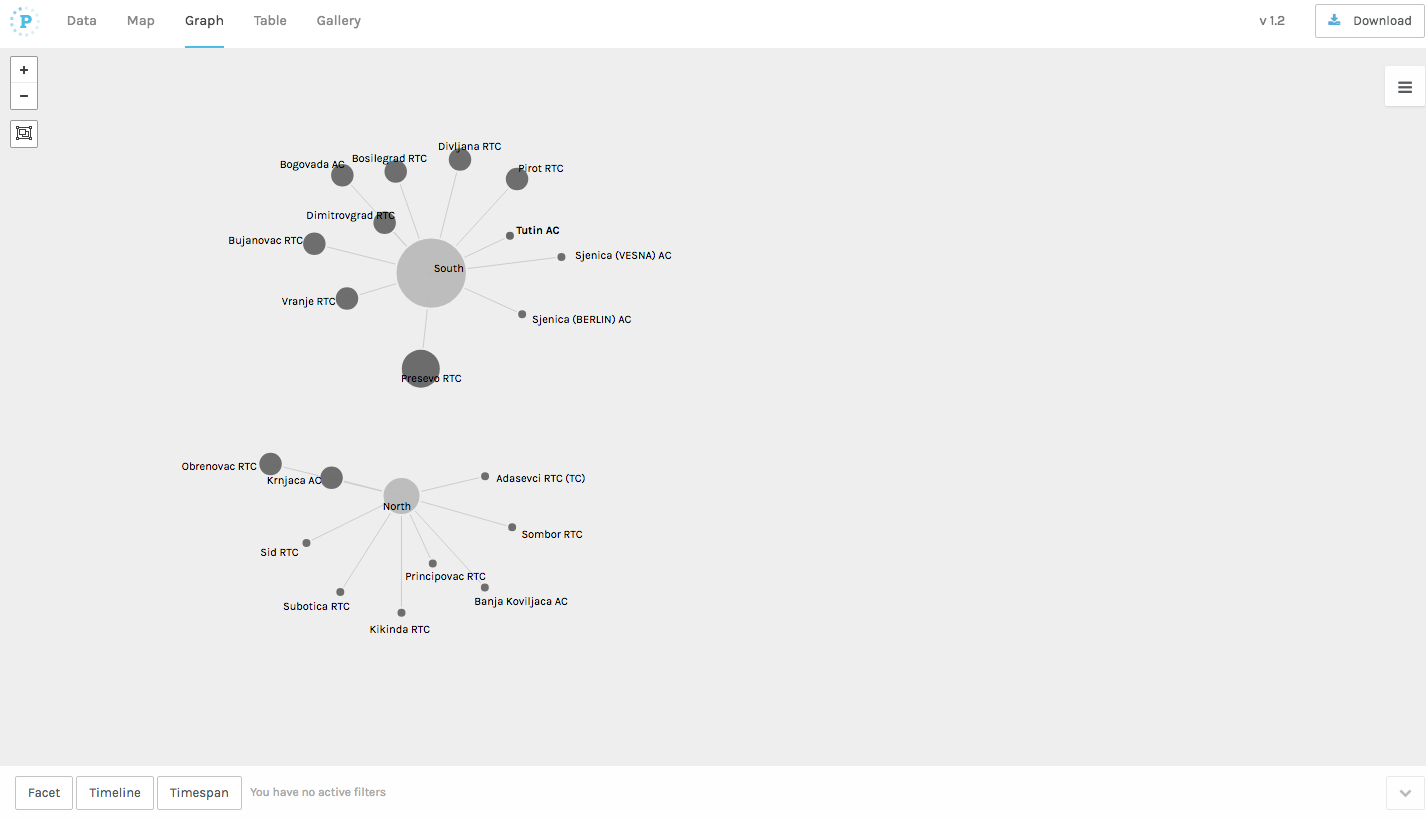

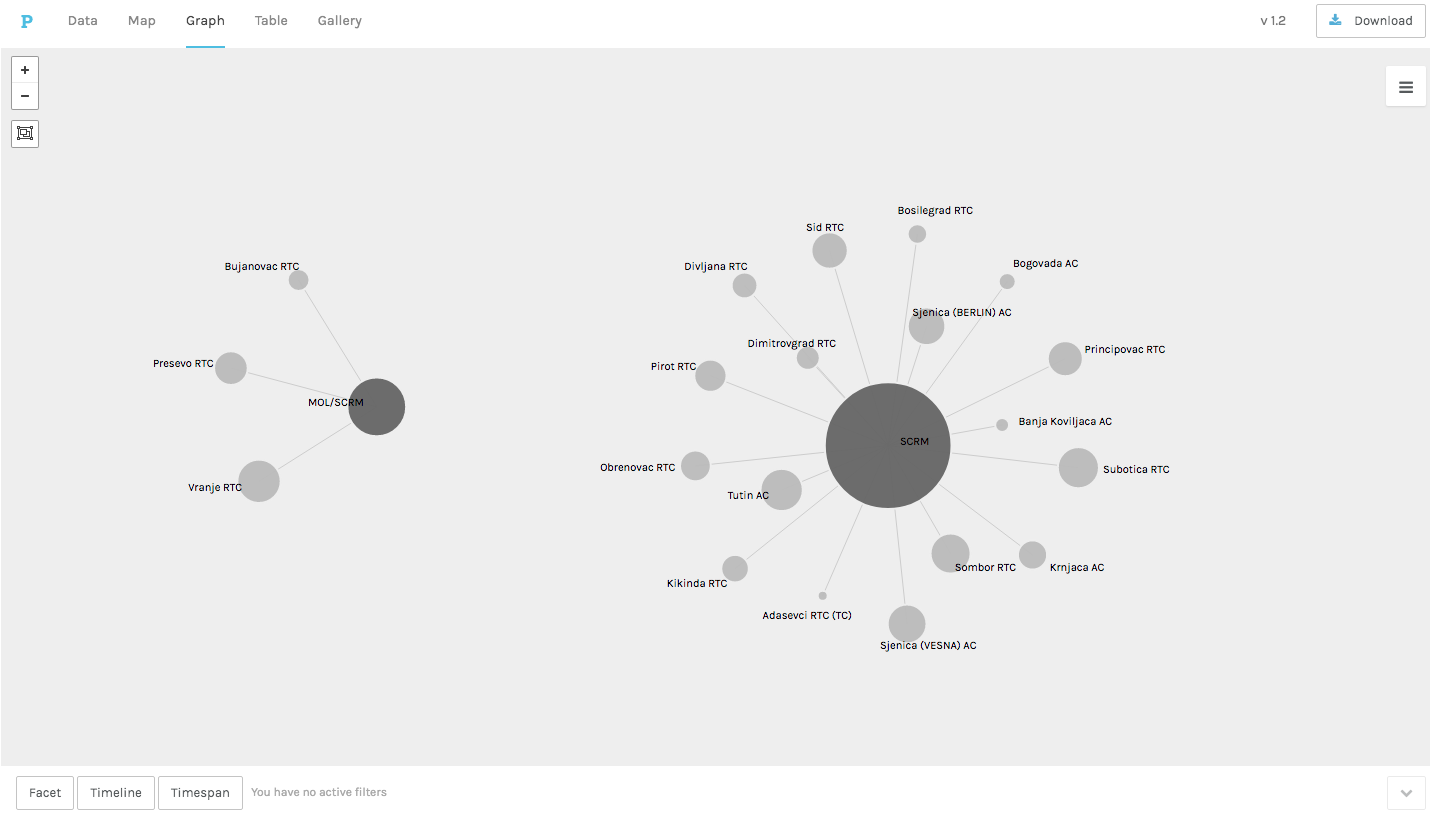

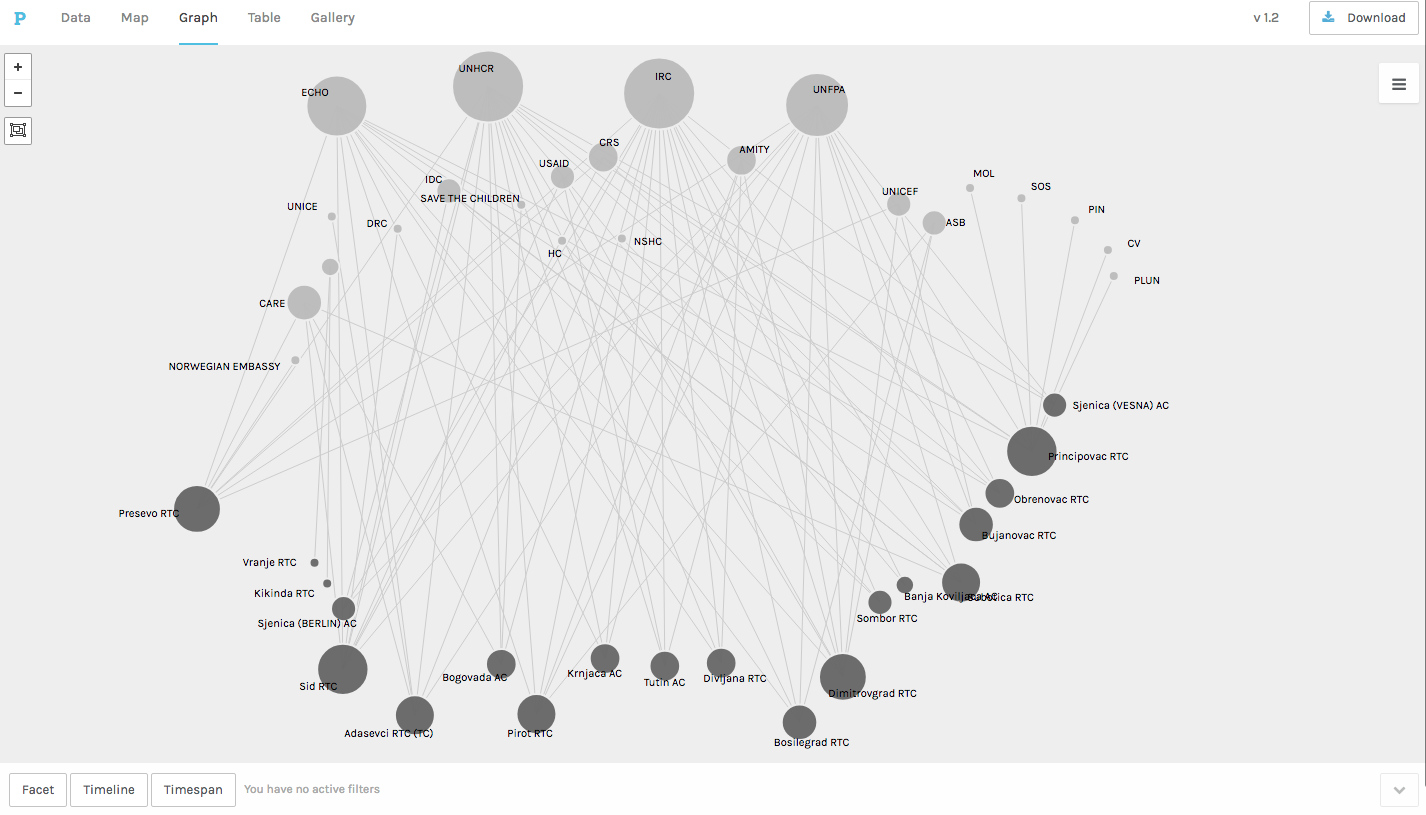

In MAP.9 the size of the node represents whether one was allowed to move out of the camp. It is clear that all southern camps introduced a restriction of movements. Similarly, in GRAPH.3, the size of each node determines whether a permit to leave is needed or not. In 2017, at the peak of the migrant presence in the country, the only exception was Preševo, which enforced a very strict rule giving only a three-hour-permit to go out of the centre (see UNHCR 2017; Komesarijat 2018), basically displaying a semi-detention system. During the years, those permits have changed several times based on the pressure put by different municipalities and the national migration management. For example, Banja Koviljača, Tutin, and Sjenica situated at the BiH and Montenegro borders did not require any permit. Limiting the movements outside of the centres has also been used as punishment, especially in the case of collective protests or small individual acts of resistance that many people reported, such as trying to cook for oneself inside the camp or hiding in the proximity of the centres.

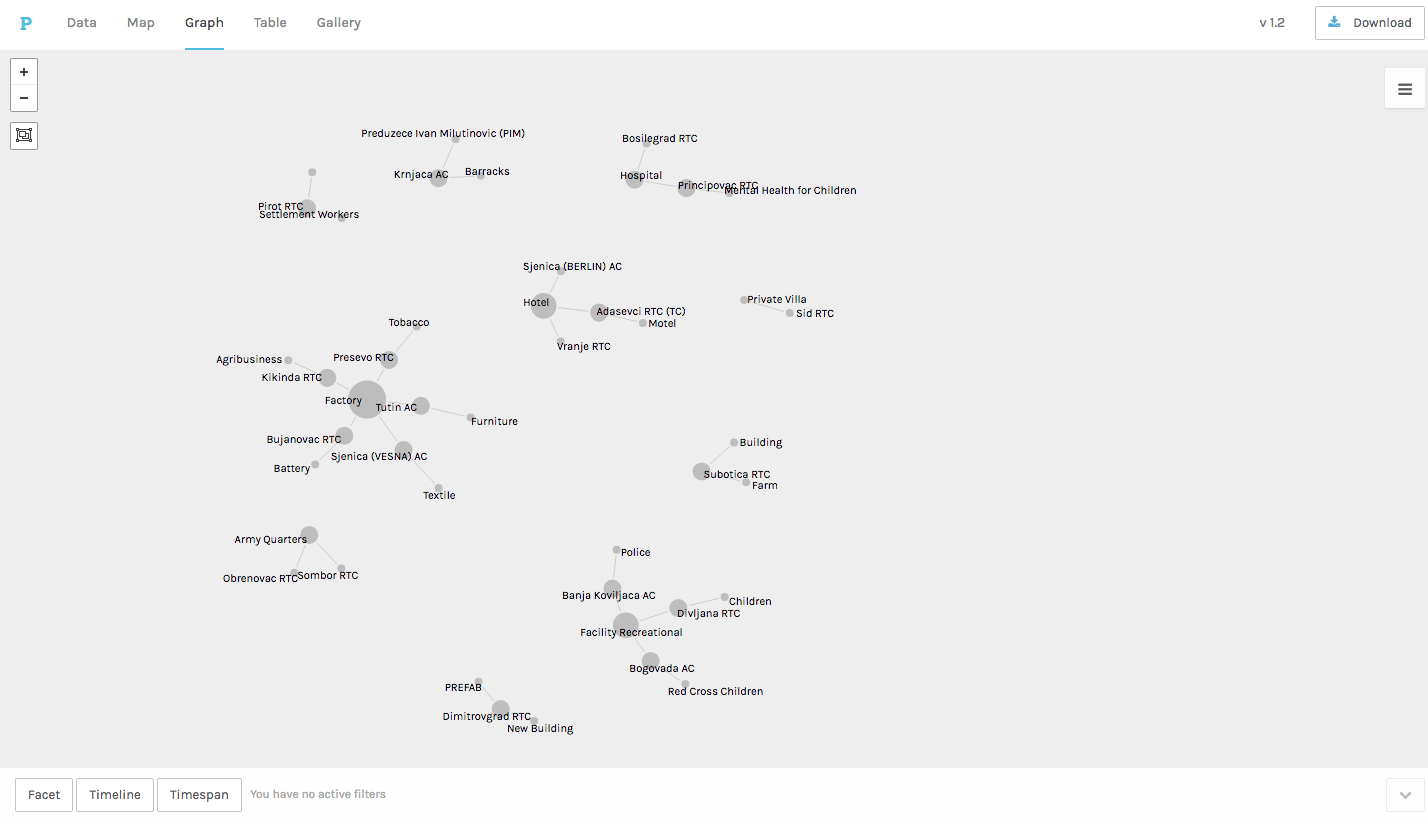

Previous Usage / Management / Donors

Asylum, transit and reception centres were opened using existing infrastructures. Several former factories were used to accommodate people on the move. In Sjenica, the so-called »Berlin« AC was, and still remains, a hotel in which asylum seekers were accommodated in common spaces at the ground floor and in the hall upstairs without any respect towards privacy and national standards for the accommodation of asylum seekers. This has been also the first form of public-private cooperation in the country. The owner of the hotel, through an agreement with the municipality, received up to eight euros per person per day from the municipality of Sjenica,5 which had a further agreement with the Serbian Commissariat for Refugees and Migration (see Ahmetasevic 2017).

It is difficult to reconstruct the meandering network of funding linking the EU institutions with UN agencies and international and local NGOs. In the graph the main donors are displayed in light grey and the camps in dark grey. The graph has been realised with data made available by UNHCR camp profiles. The main donors are ECHO, UNHCR, UN Funds for Population and Activities (UNFPA), and International Rescue Committee (IRC) and those actors are all linked to major EU funding. Such data is only available for 2017. Since 2018, Oxfam has also played an important role as leader of the food consortium financed by the EU with an approximate budget of initially 3.5 million euros in 2018 and additional 8.5 million in 2019.

From 2015 to 2017, the EU has allocated more than 130 million euros to Serbia to deal with the so-called migration crisis.

From 2018, Serbia has received a total of 58 million euros, 28 million for border management and 16 million for camps, with the addition of 14 million for food inside the camps, despite the significantly decreasing numbers of people in the country.

From 2018 to the beginning of 2019, the EU has allocated two million euros in emergency assistance, plus 7.2 million euros assistance to Bosnia and Herzegovina through UN agencies and international non-governmental organisations.

In both Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, these funds have been used to erect and rehabilitate new and old factories, motels, recreational centres, mental hospitals, private villas, and army barracks.

These funds have been used to contain and hold thousand of people in legal and humanitarian limbos outside of the EU-territory without any clear alternative or a future solution to their struggles.

The EU continues to invest millions of euros making sure the rights to mobility, residency and dignity are rights made for just a few and struggle for most!

The aim remains clear: these places must close! It is not only a theoretical issue anymore; containment camps are all around us, and we cannot just continue to write about it.

Literature

Ahmetasevic, Nidzara (2017): Refugees Stranded in Sandzak. K2.0 of 29.09.2017. URL: kosovotwopointzero.com [04.07.2019].

Ahmetašević, Nidžara / Mlinarević, Gorana (2019): People on the Move in Bosnia and Herzegovina 2018. Stuck in the Corridors to the EU. Heinrich Böll Foundation. Office for Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia, Albania. Sarajevo. URL: ba.boell.org [04.07.2019].

Belgrade Centre for Human Rights / Macedonian Young Lawyers Association / Oxfam (2017): A Dangerous »Game«. Joint Agency Briefing Paper of Oxfam International. Oxford. URL: www-cdn.oxfam.org [04.07.2019].

Beznec, Barbara / Speer, Marc / Stojić Mitrović, Marta (2016): Governing the Balkan Route. Macedonia, Serbia and European Border Regime. Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung Southeast Europe, Research Paper Series No. 5. Beograd. URL: bordermonitoring.eu [04.07.2019].

Boitiaux, Charlotte (2018): Bosnia’s Salakovac Reception Center Offers Migrants a Moment of Respite. Infomigrants of 13.07.2018. URL: infomigrants.net [04.07.2019].

Cantat, Celine (2020): The Rise and Fall of Migration Solidarity in Belgrade. In: this issue.

Dinham, Paddy (2017): Food Queue with Echoes of Europe’s Dark Past: Freezing Migrants Wait for Aid in Belgrade Today in Pictures Chillingly Similar to Those from the Second World War. The Daily Mail of 10.01.2017. URL: dailymail.co.uk [04.07.2019].

EASO (2016): EASO Guidance on Reception Conditions. Operational Standards and Indicators. EASO of 08.12.2016. URL: easo.europa.eu [04.07.2019].

European Council of Refugees and Exiles (ECRE) (2018): Serbia. New Act on Asylum and Temporary Protection Adopted ECRE of 13.04.2018. URL: ecre.org [04.07.2019].

European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operation (ECHO) (2017): EU Announces Additional €4 Million in Emergency Aid to Help Refugees in Serbia. ECHO of 09.10.2017. URL: ec.europa.eu [04.07.2019].

European Commission (EC) (2015): Refugee Crisis. New €13 Million in Humanitarian Aid for Refugees in Western Balkans. Press release of 10.12.2015. URL: europa.eu [04.07.2019].

European Commission (EC) (2019): Serbia 2019 Report. URL: ec.europa.eu [04.07.2019].

European Commission (EC) (s.a.): Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance (IPA). URL: ec.europa.eu [04.07.2019].

European External Action Service (EEAS) (2018): Serbia. EU Increases Support to Migration and Efficient Border Management. EEAS of 14.02.2018. URL: eeas.europa.eu [04.07.2019].

Graham-Harrison, Emma (2017): »They treated her like a dog«. Tragedy of the Six-year-old Killed at Croatian Border. The Guardian of 8.12.2017. URL: theguardian.com [04.07.2019].

Hameršak, Marijana / Bužinkić, Emina (Eds.) (2018): Formation and Disintegration of the Balkan Refugee Corridor. Camps, Routes and Borders in the Croatian Context. Zagreb/Munich. URL: ief.hr [04.07.2019].

Medecins sans Frontiers (s.a.): Games of Violence. Unaccompanied Children and Young People Repeatedly Abused by EU Member State Border Authorities. s.l. URL: msf.org [04.07.2019].

MacDowall, Andrew / Graham-Harrison, Emma (2017): Influx of Refugees Leaves Belgrade at Risk of Becoming »new Calais‹. The Guardian of 14.01.2017. URL: theguardian.com [04.07.2019].

Mezzadra, Sandro / Neilson, Brett (2013): Border as Method. Or, the Multiplication of Labor. Dutham/London.

Ministarstvo za rad, zapošljavanjе, boračka i socijalna pitanja (s.a.): Madad Fund. Project in the Area of Migration. URL: minrzs.gov.rs [04.07.2019].

Palladio. Visualize Complex Historical Data with Ease. Stanford. URL: hdlab.stanford.edu [03.01.2019].

Pravilnik o uslovima smeštaja i obezbeđivanju osnovnih životnih uslova u centru za azil (2008): In: Službeni glasnik Republike Srbije 31. URL: npm.rs [19.07.2019].

Republika Srbija Komesarijat za izbeglice (2008): Stanje i potrebe izbegličke populacije u Republici Srbiji. Komesarijat za izbeglice. s.l. URL: kirs.gov.rs [04.07.2019].

Republika Srbija Komesarijat za izbeglice (2018): Rulebook of the house rules in asylum centers and other facilities for accommodation of asylum seekers. URL: kirs.gov.rs [04.07.2019].

United Nation Development Program (UNDP) (2019): Interagency Operational Updates. URL: undp.org [30.10.2019].

United Nations in Bosnia and Herzegovina (UN) (2019): Monthly Operational Updates on Refugee/Migrant Situation. URL: ba.one.un.org [04.07.2019].

United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) (2017): Site Profiles. URL: reliefweb.int [04.07.2019].

United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) (2018): Site Profiles. URL: reliefweb.int [04.07.2019].

United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) (2019): Site Profiles. Copy with author.

Wodak, Ruth (2015): The Politics of Fear. What Right-Wing Populist Discourses Mean. London/Thousand Oaks/New Delhi/Singapore.

Official data are often inconsistent. The number of camps as well as their official dates of opening do not always match between the Commissariat for Refugees and Migration of the Republic of Serbia (CRMRS) official page and the UNHCR Centres Profiles.↩︎

The expulsions and limitations of movement are analysed in MAP.9/GRAPH.3, 4.↩︎

The mentioned figures neither include the Serbian component of the Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance (IPA) I and II regional programmes, nor other initiatives targeting municipalities or other institutions (EC s.a.).↩︎

In 2019 (from October 2018 to December 2019), the EU has allocated additional 8.5 million euros for the provision of food in the Serbian camps.↩︎

The same daily budget was also given to Tutin (2014), Bogovadja (2013), Krnjaca (2014). This data was acquired in an interview and shared by a colleague.↩︎