Abstract The new EU Migration and Asylum Pact, officially adopted in mid-2024, represents a continuation of increasingly restrictive and logistically driven migration policies implemented since the signing of the Schengen Agreements. This paper explores the 2018-2019 ad hoc relocation mechanism, which introduced many of the features that can now be found in the reform of the Common European Asylum System (CEAS). Through empirical fieldwork conducted in southern Italy, this study highlights the realities faced by migrants in the hotspots of Messina and the reception centre in Crotone, illustrating the logistical practices used to regulate migrant mobility and shedding light on the potential implementation of the Pact. By examining this pilot project, the paper offers insights into the operationalisation of key features of the Pact, including the Solidarity Relocation Mechanism and the concept of non-entry, which positions first reception centres and hotspots as extraterritorial zones. The Pact consolidates a migration and asylum approach increasingly defined by logistical frameworks that emphasise control, efficiency, and regulation, often at the expense of human rights and protection.

Keywords EU Asylum System, New Migration Pact, Hotspot approach, Malta Declaration, CEAS reform

The new EU Migration and Asylum Pact, officially adopted in mid-2024 after years of contentious negotiations between EU member states, seeks to address the bloc’s longstanding challenges in managing migration. The pact introduces a comprehensive framework reforming the Common European Asylum System (CEAS), scheduled for full implementation by mid-2026.

While the Pact is not yet operational, insights into how some of its key features might function can be drawn from the 2018–2019 ad hoc relocation mechanism. This earlier initiative provides a practical precedent for two key elements of the Pact. The first is the solidarity mechanism, designed to redistribute asylum seekers, after arriving at the EU’s southern borders between member states. The second is the concept of non-entry, whereby individuals crossing borders irregularly are not considered to have formally entered the EU territory until they complete a border procedure. This approach designates first reception centres, such as the so-called hotspots, as extraterritorial zones for processing arrivals.

The Pact consolidates a migration and asylum approach increasingly defined by logistical frameworks that emphasize control, efficiency, and regulation, often at the expense of human rights and protection.

This article explores the evolution of the EU’s logistical approach to migration and asylum, with a focus on the implementation of the hotspot system and the ad-hoc relocation mechanisms that were in force from June 2018 to September 2019. Drawing on fieldwork conducted in the south of Italy between June 2018 and January 2020, this analysis highlights how logistical practices have been used to regulate and exploit migrant mobility while maintaining an illusion of solidarity between EU member states. By examining the intersection of logistical efficiency, securitisation, and human rights violations, the article sheds new light on the broader implications of the New Pact and its role in perpetuating a migration regime that prioritises exclusion and exploitation.

In a first step, I will introduce the theories informing this paper. The logistification of migration management emerged prominently after the 2015 »long summer of migration« (see Hess et al. 2017) but has origins in the 1985 Schengen Agreements. While Schengen facilitated free movement in the EU space for nationals of EU member states, it also raised concerns about ›undesirable‹ migration, leading to the securitisation of migration. Using a logistic gaze (see Mezzadra 2017) on migration management allows us to analytically dissect the spatial technologies adopted to implement this infrastructure. One of these technologies is the hotspot approach, whose key features and operational implementation will be described in the second section.

Following the theoretical discussion, I analyse the implementation of the temporary relocation mechanism by exploring its historical context and positioning it within the broader trend of the EU’s shift towards more restrictive and conservative migration policies. Subsequently, I examine the empirical application of the temporary mechanism at the Messina hotspot and the Crotone reception centre, illustrating how the logistical framework functions in practice. This analysis highlights the inadequate living conditions and prolonged uncertainty faced by migrants awaiting relocation, revealing how the EU’s emphasis on logistical efficiency and surveillance often undermines migrants’ rights and overall well-being.

The redistribution procedure section outlines the European Asylum Support Office’s (EASO) Standard Operating Procedures (SOP) for relocation, highlighting the varying approaches adopted by different EU countries like Germany and France. The analysis illustrates the opacity, arbitrariness, and underlying deportation logic driving EU relocation processes. In the last section, I will go back to the new EU Migration Pact showing how elements of the temporary relocation mechanism are being institutionalised within the new legislative framework, highlighting a continuity of exclusionary practices and a logistical emphasis.

My ethnographic engagement in Italy lasted around 18 months, monitoring the relocation procedures implemented in the Sicilian hotspots, and in the reception centre in Crotone. The methodology implemented is strongly inspired by studies in investigative and militant anthropology, which have contributed to unveiling human rights violations and increase accountability of state (and non-state) actors, while ensuring dignity and justice for the subjects of the investigation (see Scheper-Hughes 1995; Juris 2007; Fondebrider 2015). Investigative anthropology can uncover the often-hidden mechanisms and systemic injustices within border regimes, such as discriminatory policies, bureaucratic inefficiencies, and the socio-political dynamics shaping asylum processes.

This research primarily aimed to investigate the procedures, while providing legal support to the asylum seekers awaiting the relocation process.1 This approach addresses challenges related to working in a politically sensitive environment and to the colonial history of ethnography (see Pels/Salemink 1994; Pels 1997) by positioning researchers as allies who actively support asylum seekers while documenting their struggles.

Logistics of Asylum

While the process of logistification of migration and asylum is more evident since the 2015 ›long summer of migration‹, its origins can be traced back to the Schengen Agreements. Signed in 1985, these agreements established a border-free zone within the EU, allowing for the unhindered movement of goods, capital, and EU citizens. While celebrated for facilitating economic integration, this openness also raised concerns about controlling ›undesirable‹ movements, particularly irregular migration, organised crime, and smuggling. For the first time, irregular migration was formally framed as a security issue, criminalised it within EU policy, and linked to broader threats such as terrorism and transnational crime (cf. Longo 2002; Ceccorulli 2019).

Through this securitisation, migration became seen not only as a logistical challenge but as a fundamental threat to public order, embedding a criminalising perception of migrants and asylum seekers into EU governance (see Walters 2002). The Common European Asylum System emerged as an attempt to uniform EU national legislations to control the entrance within the open area of Schengen. For instance, the Dublin Regulation determines which EU member state is responsible for processing an asylum application submitted by an individual seeking international protection. While it provides for a specific hierarchy of responsibility—including family reunification—in most cases, the country of first entry typically becomes responsible for processing the asylum claim (see Brekke/Brochmann 2015; Høglund 2017). This measure prevents ›secondary movements‹ —that is, it stops asylum seekers from relocating between different EU countries, to avoid multiple asylum application or in pursuit of better welfare provisions.

To control movements within the Schengen area, a new framework for managing migration emerged, characterised by a series of spatial and institutional innovations (see Altenried 2017). These include biometric controls (cf. Scheel 2018), data-driven border management systems like the Schengen Information System and Eurodac, a network of camps and processing centres distributed across and beyond EU borders. The biometric surveillance permits the implementation of the Dublin regulation by tracking migrants crossing into different EU member states through control checkpoints situated at the internal borders of the EU (see Pollozek/Passoth 2019). This proliferation of borders, described by Mezzadra and Neilson (2013), illustrates the extent to which asylum and migration policies are refined mechanisms of mobility containment.

The asylum system also depends on an intricate bureaucratic framework of permits, legal categories, and administrative processes that control migrants’ movements and rights.2 It is increasingly externalising EU borders by shifting asylum procedures to peripheral regions and neighbouring states (see Casas-Cortes et al. 2017), while simultaneously forging agreements with authoritarian third countries to intercept and deter irregular migration (see Heck/Hess 2017; Vari 2020; Natter 2023).

These developments align with what has been termed the »logistification« of migration—a conceptual shift in which migration management increasingly adopts the principles and the language of logistics (see Vianelli 2017; Altenried et al. 2018; Bojadžijev 2021). In the past 25 years, as migration governance became a priority for EU states, terms such as ›hotspots‹, ›hubs‹, and ›corridors‹ began to dominate the discourse, reflecting the adoption of logistical strategies initially developed for the management of goods (see Altenried et al. 2018). Logistics thus became a tool for regulating the movement of people, transforming migrants into units of circulation to be managed, controlled, and directed (see Vianelli 2022).

This framework draws from the historical roots of logistics, as Grappi (2016) explains, originating in military strategy where it focused on the efficient deployment of troops and resources. In the context of modern global capitalism, logistics evolved into a system for ensuring the seamless movement of goods across space.

De Landa (2006) notes that while logistics originally adapted to pre-existing strategies, this relationship has reversed in recent decades. Today, strategies, organisational structures, and transportation systems are increasingly driven by logistical considerations. This reversal is evident in migration management, where logistical concerns shape the strategies, policies, and infrastructures governing human mobility.

The shift from capitalistic logistics to migration management is a matter of emphasis: with globalisation, logistics has become »the art of constructing a seamless administration of circulation across space« (Krifors 2020: 3), and this emphasis on circulation has enabled the transition from managing goods to managing bodies—especially the undesired ones.

Migration management adopts this logic, applying it to regulate the movement of bodies deemed ›undesirable‹. Migrants, much like goods, are contained, categorised, and redirected through infrastructures that both isolate them and exploit their labour. In this sense, logistics serve as a contemporary tool for transforming migration into a controlled and economically productive process. This phenomenon is what has been defined as »differential inclusion« (see Mezzadra & Neilson, 2013) or the »ex/inclusion paradigm« (see De Genova 2013), where exclusion from social and legal rights paradoxically facilitates inclusion within illegal or marginal forms of labour.

At the heart of this system there is a »migration infrastructure« —a network of actors, institutions, and technologies that work together to manage asylum and migration (see Xiang/Lindquist 2014). This infrastructure includes state bureaucracies, international humanitarian organisations, private companies, and migrants themselves, all interconnected through logistical processes. Camps and migration centres serve as hubs within this network, functioning as nodes where regulatory, commercial, and labour systems intersect. Paradoxically, these centres are both invisible—due to their geographic isolation—and hyper-visible, as they are sites of intensive surveillance and control.

Reception centres for asylum seekers, in particular, epitomise the dual role of isolation and inclusion. Located at the peripheries of urban areas or near external EU borders, they physically separate migrants from mainstream society while integrating them into specific economic systems as a source of cheap, precarious labour (cf. Platania 2021). Thus, camps operate as logistical nodes, funnelling migrants into economic circuits while maintaining tight control over their movements.

The logistification of migration management reveals the EU’s dual priorities: maintaining control over mobility while extracting economic value from migrants. Through its logistical framework, migration management transforms camps and borders into mechanisms of control, surveillance, and economic exploitation, highlighting the entanglement of security, economy, and governance in the contemporary asylum regime.

This, however, does not suggest that the migration regime entirely strips asylum seekers of their agency. While asylum policies have often been utilised to channel migration into narrowly defined legal categories, migrants themselves have appropriated these frameworks, using asylum as a pathway to gain entry into the EU (see De Genova/Garelli/Tazzioli 2018). Furthermore, since the turn of the century, self-organised migrant movements and pro-migrant advocacy groups have flourished, transforming migration into a highly contentious and politically charged issue (see Della Porta 2018a; 2018b; Ataç/Steinhilper 2022). The increasingly restrictive policies and the reinforcement of internal border controls stem from the persistent efforts of migrants to cross borders, often employing strategies to evade interception

The Hotspot Approach

A key spatial device in this framework is the hotspot approach, first implemented in southern Italy and on some Greek islands, it functions as border-buffer zone, containing migration at the external borders. Hotspots serve as sites for initial identification and screening, where migrants are catalogued into a unified dataset (see Bousiou/Papada 2020). These hotspots thus act as central hubs for the registration process, facilitating the creation of comprehensive data on migrants.

The hotspot approach marks a significant turning point in the logistification of migration management in the European Union, reflecting the reduction of migrants to objects of bureaucratic and logistical control. Introduced by the European Commission in 2015, the hotspot system was initially framed as a flexible emergency mechanism designed to manage crises by containing and identifying large numbers of people. Even though the alleged ›migration crises‹ of 2011 and 2015 were largely the results of EU divestment of reception facilities (see Holmes/Castañeda 2016) and the failure of agreements with neighbouring countries (see Hess/Kasparek 2017), EU leaders responded to the influx of people with the implementation a series of security measures that established a system for processing asylum applications and gathering biometric data—all primarily aimed at enforcing the Dublin Regulation.

The hotspot system operates with a high degree of discretion, as it does not officially specify the facilities involved nor the agencies responsible (see Kasparek 2016). The intended adaptability of the approach has revealed deeper issues tied to exclusion, exploitation, and the erosion of migrants’ rights.

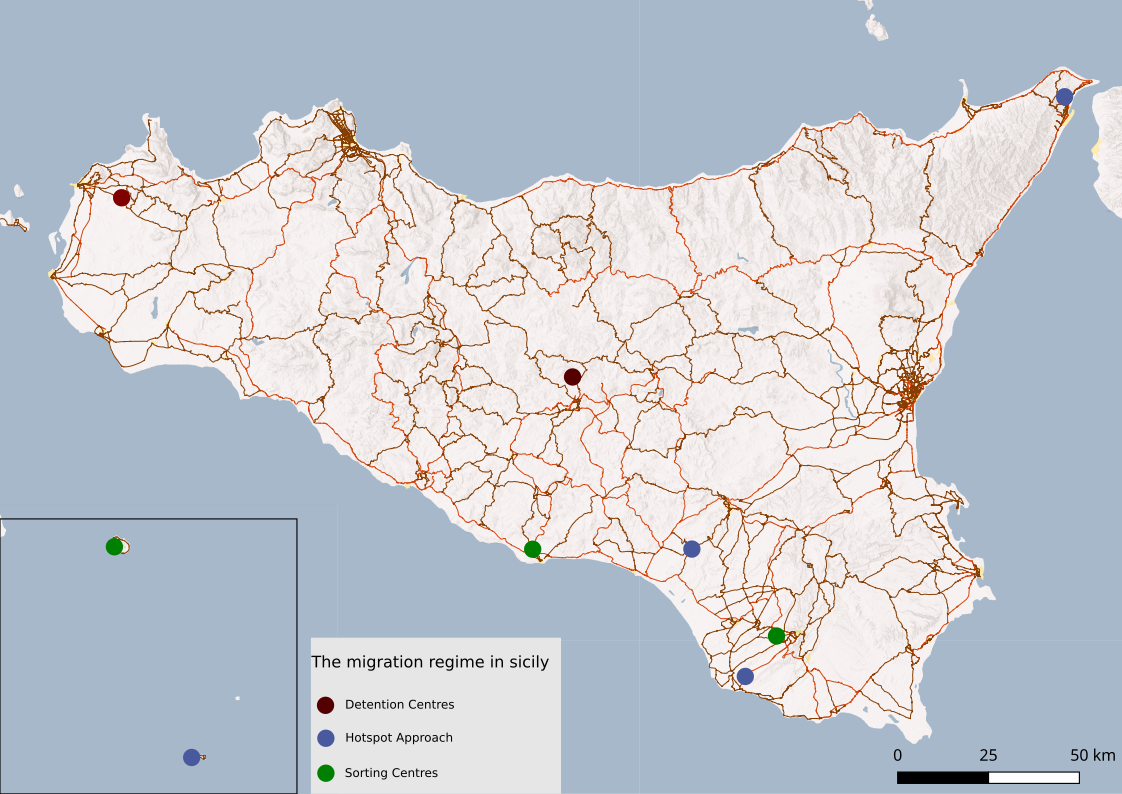

At its core, the hotspot system introduces a European-wide data infrastructure that registers individuals and shares information across multiple authorities (see Hess/Kasparek 2017; Scheel 2019; Pollozek/Passoth 2019). This infrastructure simultaneously divides migrants into distinct legal categories, such as asylum seekers, persons from ›safe third countries‹, individuals subject to relocation, or those earmarked for deportation (see Garelli/Tazzioli 2016; De Genova 2017). These categories determine access to services and rights, creating stark hierarchies between migrants. Hotspots function also as tools of mobility control, using both legal frameworks and localised rules to restrict movement. Situated predominantly in remote and rural areas, they further isolate migrants, effectively excluding them from participation in civil society while channelling their labour into exploitative sectors, such as agriculture in southern Italy (see Perrotta 2014; Howard/Forin 2019; Meret/Aguiari 2020). Thereby, they are producing differential inclusion.

Hotspots are not static physical locations but rather dynamic nodes within a broader logistical system, operating as high-intensity circulatory hubs where regulated and autonomous mobilities intersect (see Tazzioli 2018). Decentralised and over-regulated, they function as peripheral zones of control, removed from urban centres and shielded from public scrutiny (see Platania 2021). In Italy, for example, hotspots have been concentrated in Sicily, at the southernmost border of the EU, with facilities in Lampedusa, Messina, Pozzallo, and Trapani. While initially designed for identification and containment, their roles have expanded, with newer facilities emerging in locations like Pantelleria and Agrigento to handle increased arrivals and facilitate redistribution. These centres can be activated and deactivated seamlessly, akin to a water tap, depending on the volume of arrivals and the logistical priorities of the moment. This operational fluidity reflects a conception of migration as a controllable and episodic phenomenon rather than a structural reality.

Hotspots, therefore, have become emblematic of the EU’s logistical approach to migration. They are not merely administrative tools but have evolved into warehouses for commodified bodies, where migrants are sorted, catalogued, and redirected according to a taxonomy based on ethnic and racial categories as much as bureaucratic and economic imperatives. By prioritising control and efficiency over humanitarian considerations, the hotspot approach perpetuates structural inequalities and reinforces the EU’s role in sustaining a migration regime that is both exploitative and exclusionary.

The Ad-Hoc Relocation

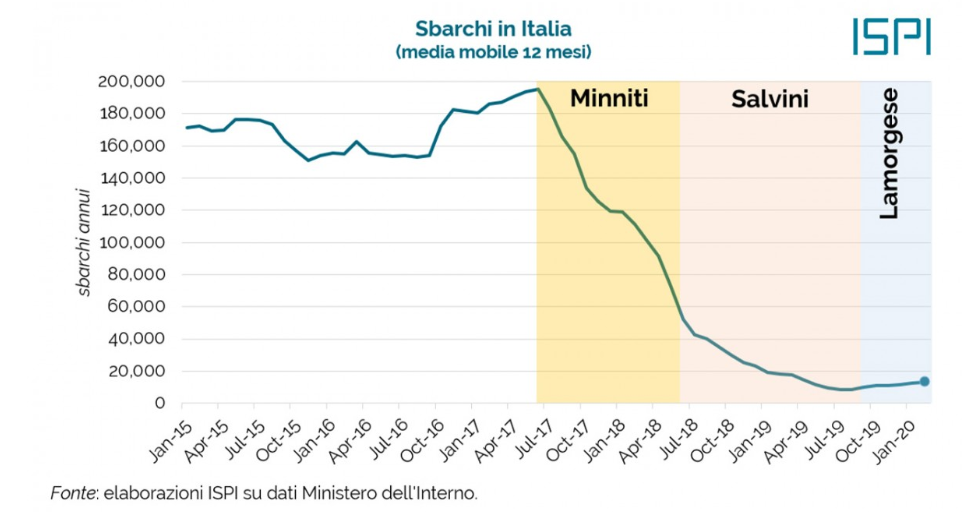

In the summer of 2018, Matteo Salvini, Italy’s Minister of the Interior and leader of the far-right party La Lega, announced that Italian ports would be closed to migrant disembarkations. This statement was part of his broader political campaign against ›irregular‹ migration, which he framed as a crisis that threatened Italy’s sovereignty. Salvini’s rhetoric, emphasising slogans like »stop the invasion« and »Italians first«, was designed to capitalize on growing fears of migration (see Stille 2018).

While the 2018 and 2019 period saw a decrease in arrivals, Salvini’s ›closed-port‹ policy was never fully implemented. In reality, the reduction in migrant numbers was largely the result of agreements made by his predecessor, Marco Minniti, with the Libyan government, which had begun to take effect before Salvini assumed office. These agreements, aimed at curbing departures from Libya, were key in reducing migrant flows, but Salvini appropriated their success to promote his hardline stance on migration.

This decrease led to a reduction in media coverage of the arrivals, as the focus shifted to the role of NGOs in Mediterranean rescue operations. Salvini remained committed to his promise of ›zero disembarkations‹ by systematically denying entry to Italian ports for NGO rescue vessels, forcing them to remain stranded at sea for prolonged periods before being assigned a port for disembarkation.

A crucial part of Salvini’s strategy involved his desire to undermine the Dublin Regulation, which mandates that asylum seekers must apply for asylum in the first EU country they enter, pressuring southern EU member states. This regulation has long created tension between EU member states, particularly between the southern states and the northern states. Salvini’s political manoeuvring aimed to use the media spectacle of stranded rescue ships to pressure other EU states into either accepting migrants for relocation or providing a port for disembarkation (Il Post 2019).

The first major ›sea crisis‹ occurred in August 2018 when the Aquarius, a rescue vessel, was denied entry to Lampedusa and left stranded at sea for over a week. This stand-off sparked negotiations between EU member states, resulting in the vessel being allowed to dock in Spain. According to the Instituto Per gli Studi di Politica Internazionale (ISPI), this event marked the beginning of a series of 25 similar crises, during which rescue ships were forced to wait for extended periods—averaging nine days—before a port was assigned, depending on informal agreements between EU countries about relocation quotas (see ISPI 2020a; 2020b).

These maritime stand-offs persisted even after a change in government in Italy, from Salvini’s right-wing coalition to a more left-leaning administration —under the new interior minister Luciana Lamorgese. The new government ratified the Malta Agreements in September 2019, which established a temporary solidarity mechanism between several EU countries for the relocation of migrants arriving via rescue operations. The Malta Agreement aimed to streamline relocation procedures, introducing a six-month pilot project to facilitate faster, voluntary relocations. However, it continued the trend of using SAR (Search and Rescue) vessels as the primary means for relocation, a process that remained highly selective, as only 9 percent of arrivals disembark from one of the civil fleet vessel, according to ISPI (cf. ISPI 2019).

The signing of the Malta Agreements by a more pro-EU political force, such as the Partito Democratico—echoing the approach taken with the Memorandum with Libya—underscores the European Commission’s ongoing efforts to reform the CEAS. This reform trajectory signifies a shift towards more restrictive migration policies, driven by the rising anti-migration sentiment within EU public opinion. In an attempt to counter the growing influence of far-right parties, mainstream political forces increasingly adopted hardline stances, embedding restrictive practices into both national and EU migration policies.

Salvini’s assertive approach served as a catalyst in this process, pressuring the European Commission and northern EU member states—traditionally reluctant to support comprehensive CEAS reform—to address migration challenges with greater urgency and decisiveness. Consequently, the temporary relocation mechanism had significant political and operational impacts on the development of the New Migration Pact, functioning as a testing ground for the broader CEAS reform framework

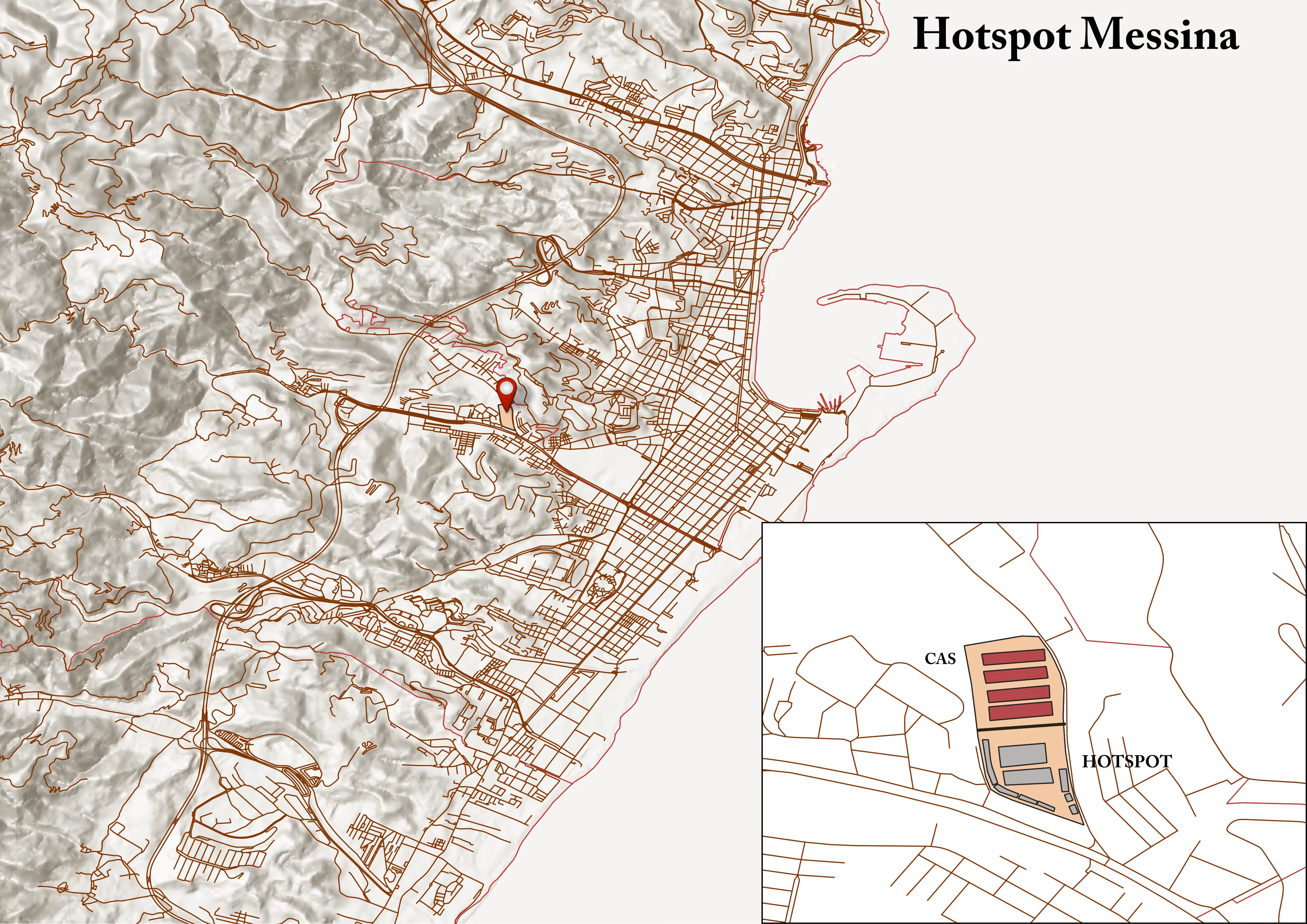

The Messina Model

The Messina hotspot, located at the former Caserma Visconti military barrack, is situated on the outskirts of the city, near the highway, about a 30-minute walk uphill from down-town. The centre is made up of two large hangars separated by a fence, with shipping container housing units surrounding them, each holding up to four people. These two sections of the centre operate independently: the first is a Centro Accoglienza Straordinario (CAS), a standard reception centre, and the second is the so-called hotspot, accessible only after passing through a guarded gate. Upon entering the hotspot, a tensile structure leads into the main hangar, where initial medical checks are performed.

During my fieldwork, I was never authorised to enter within the premises of the hotspot. Most of the conversations and interviews have been conducted outside the perimeter of the facility, in an adjacent square. At the beginning of the relocation process, I met F., a man who had been rescued by an NGO SAR vessel after spending more than eight days stranded at sea. F. was awaiting relocation, and he was eager to speak because, since his arrival, he had not met anyone who could communicate with him in a language he understood, even a colonial lingua franca. He shared his dissatisfaction with the conditions in the camp. Despite having been there for months, he was still living within the hotspot. Only after six months would he be moved to the other side of the fence, to the CAS.

Inside the hotspot, F. explained that all individuals from various SAR disembarkations were placed together in the main hangar, with no special attention given to vulnerable individuals, such as minors. The space was overcrowded, with more than 70 mattresses on the floor, and lacked basic privacy, sanitation, and necessities such as soap and detergent for washing clothes. In addition, residents were required to return to the facility by 8 pm, while those in the CAS had until 10 pm. F. often found himself sleeping outside the hotspot when he returned after curfew.

The greatest frustration, however, stemmed from the uncertainty of his situation. F. told me:

»Every week I ask, and they say wait, wait, wait… I went to the police, gave my information, and they told me to wait… I’m tired of waiting. They said France has to take me, but I don’t know when. One year I’ve been here, and others are getting their permits, but not me.« (F. August 2018)

The uncertainty about his future wore him down. The lack of information and the permanent waiting is typical of the asylum system. Dempsey (2018) defines wait as non-linear violence, showing to what extent it can trigger psychological trauma, especially in already vulnerable individuals.

As I continued my visits to the hotspot, I met E., a Cameroonian man who had also been rescued by an SAR vessel and was waiting for relocation. E. had been promised relocation to Germany, but many others, who were supposed to be relocated to France, had already left, while he was still waiting to be interviewed by the German delegation. He introduced me to others in the camp, including a woman with a young child who had not received medical care since disembarking, and an adult male with scars from his time in Libya that had reopened due to a lack of treatment.

According to them, the operators of the camp denied basic medical interventions as they were not asylum seekers registered in Italy. They kept repeating the same mantra: »Germany will take care of you once you’re relocated«, but no one knew when that would happen. According to E., the only way to get anything done was to protest. He told me that, to receive even basic painkillers, he had to argue and shout at the operators. Only when tensions escalated would the staff finally meet their requests.

As Ambrosini and Campomori note the hotspot becomes a »battleground« (2020) where asylum seekers must struggle their basic needs with authorities. Requests for soap, medical treatment, or updates on asylum status are often met with frustration and delay. The lack of information, combined with harsh living conditions, fosters unrest. Protests and riots are common in such reception systems.

Meanwhile, the reception system itself is framed in logistical terms. The European Asylum Support Office (EASO) has highlighted Messina as the ideal location for relocation logistics, despite frequent reports of inhumane conditions. According to EASO documents, the so-called ›Messina model‹ was introduced as a streamlined relocation procedure (see EASO 2019a). The model combines the reception centre with the hotspot, allowing all relocation operations to occur in the same facility, eliminating the need to transfer people elsewhere. While the relocation process was initially promised to take no more than four weeks (see EASO 2019b), many individuals waited for over a year and a half before being relocated.

The integration of the CAS and hotspot into a single management structure reduced operational costs by 18 percent. However, the private company that runs the facility, Badia Grande, has faced numerous criticisms for the treatment of migrants and the poor conditions at its other reception facilities in Sicily (Alqamah 2020). The logistical efficiency achieved by consolidating services and agencies allows for tighter control over the people housed there. Individuals are moved between sections of the facility depending on the system’s needs, with all procedures—interviews, medical checks, and relocations—conducted within the same centre.

Messina has effectively become the central hub for the relocation process, with all relevant agencies and delegations from other EU member states operating on-site. While the aim is to streamline operations and reduce costs, the reality for many residents is one of prolonged uncertainty and deprivation, with basic needs often going unmet. The system prioritises efficiency and control over the well-being of those it is meant to serve, and the conditions at the hotspot reveal the tension between logistical management and human dignity.

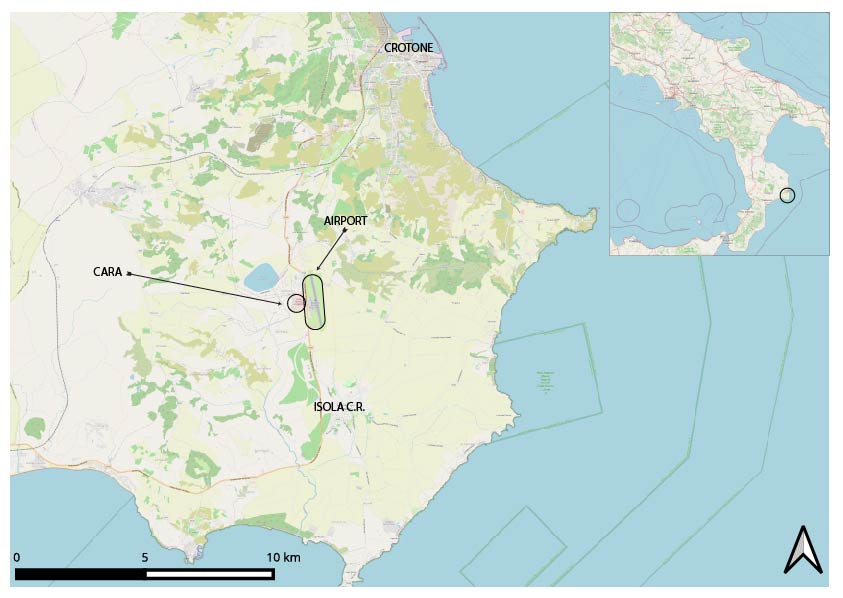

The CARA in Crotone

As disembarkations continued and not all people had been relocated, some were moved to Crotone, awaiting transfer, as the centre in Messina was nearing full capacity. The Sant’Anna CARA [Centro Accoglienza Richiedenti Asilo/Reception Centre for Asylum Seeker] in Isola Capo Rizzuto, sometimes referred to as the CARA of Crotone (due to the proximity of the larger city), is a vast reception centre for asylum seekers exemplifying the exclusionary logic inherent in migration management and demonstrates how the location of such centres is chosen primarily for logistical convenience.

I decided to go to Crotone to visit some of the people that I had met in Messina. When I arrived, I realised the centre was actually not in Crotone, but in a remote area, surrounded by agricultural fields and an airport, with Isola Capo Rizzuto located nearly 6 km away and Crotone about 16 km further. The camp’s isolation is evident when driving toward it, where it is common to see asylum seekers walking or cycling along the high-speed road connecting the centre to the urban areas. Public transportation offers limited options: to reach Crotone, one must first travel to Isola, then take a bus from there. The bus service provided by the camp itself is often out of service and left parked within the camp’s premises. As a result, the only potential work opportunities are in the surrounding fields, where asylum seekers are often exploited due to their precarious status (Della Puppa/Sanò 2021; Meret/Aguiari 2020).

The CARA is a sprawling complex, including housing, facilities, and shipping containers, capable of accommodating over 2,000 people. Once the largest camp in Italy, it was eventually overtaken by the CARA in Mineo. Over the years, the centre has attracted numerous criticisms and lawsuits for its degrading conditions. In 2017, 68 individuals linked to the camp were arrested for mafia affiliation, having infiltrated various services within the asylum system, such as canteens and cleaning services.

It was just before the first lockdown in March 2020 when E. and several others awaiting relocation to Germany were transferred to Crotone from Messina. Having been in Italy for at least six months, they saw the move as a positive sign, especially because of the proximity to the airport, which they could see from the camp. However, even in Crotone, no new information was provided, and the indefinite wait continued to frustrate asylum seekers. E. shared his experience:

»I finished everything. Germany accepted me, gave me everything, and said they would come to take me to Germany… but Germany never came. They kept saying: ›Tomorrow, next month, next month, next month‹ again and again«. (E. February 2020)

During my visits, I saw many residents leave the camp just before curfew, which was set at 10 p.m. and E. explained that since they could not return after curfew, many would go to Isola to drink something and sleep in the surrounding bushes. The camp itself was heavily guarded. On one occasion, I was asked to bring bags of clothes from the local Caritas office. E. and the others were nervous about bringing the clothes back into the camp, as everything would be thoroughly checked. After confirming that the bags contained nothing that could cause trouble, the guards allowed them to enter. It took over half an hour for them to pass through the security checks and clear the guards.

W., a Nigerian woman who was relocated to Germany in the summer of 2020, called me after her asylum application was rejected in Germany. Reflecting on her time in Crotone, she said:

»Crotone is like a prison. It’s like a prison because you don’t have the freedom to do what you want to do. They don’t allow you to cook, they don’t give you money. They give you just a key. It’s one key, and they’ll ask you to buy something from the canteen—Pepsi, biscuits, baby food. You can’t even buy a card to call your family.« (W. January 2021)

The key she referred to was an electronic device where pocket money was loaded, forcing residents to buy from the camp’s vending machines or small shops. This setup ensured that the money given to asylum seekers cycled back to the organisation running the camp. W. continued her account of life in Crotone:

»When I was in Crotone, I had a problem with my eyes. I walked to the hospital to complain, to ask for eye drops. They didn’t give them to me. They told me to come back the next day for the eye drops. I kept asking them, ›Why can’t I just take the eye drops home?‹.« (W. January 2021)

She also described the poor quality of the food and the lack of communication with her family, which was exacerbated by the camp’s policies.

»The food they give us sometimes isn’t even good. When you enter the gate, they search you, they don’t want you to cook for yourself. You can’t even buy a phone card to call your family. Our families are complaining that they don’t hear from us, but there’s nothing we can do about it. We went to the office to complain, asking them to buy cards for us, but they said they couldn’t do it.« (W. January 2021)

W.’s account highlights the poor standards of the camp: inadequate medical care, substandard food, no Wi-Fi, implying the inability to communicate with family members. These conditions reflect the extent to which the reception system has become a form of detention, where people are trapped by a series of regulations.

The Redistribution Procedure

The European Asylum Support Office (EASO) has outlined standard operating procedures (SOP) for relocation, which are divided into three main phases, plus a fourth phase—the transfer itself (see EASO 2019b). The first phase consists of standard procedures typically implemented in hotspots, regardless of the type of disembarkation. This includes individual identification followed by a health check. Afterward, a list of individuals to be relocated is compiled and shared with states willing to accept a portion of those from the disembarkation.

The second phase is specifically tailored to the relocation process itself. It involves an individual assessment conducted by EASO, which includes evaluating criteria such as vulnerability, familial ties, and cultural connections. After this interview, individuals are matched with a specific country based on unspecified ›indications‹ from the relocation countries. These countries may optionally conduct a follow-up interview with the asylum seekers. This phase highlights the opacity and arbitrariness of the relocation process. By comparing Germany and France, two of the countries accepting the largest number of relocated individuals, we can see how different countries have adopted divergent methodologies for processing relocation.

A., whom I met in Messina, shared his experience with me. Initially, he had been in Pozzallo, another Sicilian hotspot, where he was interviewed by a French delegation. He later discovered he had been rejected via a public list posted on the wall of the hotspot, containing the names of those accepted for relocation to France. No one had informed him about the reasons for his rejection or what would happen next. He asked me to investigate further, so I filed a FOIA (Freedom of Information Act) request through Borderline Sicilia to the Dublin Unit. The response stated that he was still in the process of relocation and was considered a ›European asylum seeker‹, a new terminology to indicate that no state had been assigned to him yet. A few months later, after all the other people from his disembarkation had already left for France, I filed another FOIA inquiry whether A. had been rejected. The response claimed that he had been denied due to the French delegation not believing his personal story.

The French delegation’s rejection of A. seemed unrelated to the relocation process itself. According to the SOPs, the delegation’s role is limited to performing security checks, not assessing whether an individual might be eligible for international protection. Most of the people relocated to France during my fieldwork obtained their residence permits within the first week of their stay in French territory, often rejecting those who wouldn’t be able to obtain documentation in Sicily itself. This case illustrates how the French delegation externalised asylum interviews to Sicily, effectively bypassing the asylum process in France for those who might not be granted protection.

Germany, on the other hand, adopted a different approach. Their interviews in Sicily were primarily security checks, without considering the possibility of asylum protection in Germany. Once relocated to Germany, individuals had to restart the entire asylum process, despite having already waited over a year for transfer. Through a FOIA request, in collaboration with Borderline-Europe and Sea Watch, we sought more information from the German government about the relocation procedure (see Drucksache 19/22370).

The document we received from the German government revealed that most of the people relocated to Germany came from ›third safe countries‹. For these individuals, a specific accelerated procedure was followed, which usually leads to a rejection within seven days (see Bosswick 2000). According to the FOIA response, only 31 out of 259 cases resulted in protection being granted by a court, meaning that 89 percent of the relocated individuals were ultimately rejected, receiving only a ›tolerated permit‹ (Duldung). This rejection rate aligns with the general rate of asylum rejections in Germany (see Eurostat 2019). However, it is noteworthy that individuals selected by the German delegation had little chance of obtaining protection in the first place.

E., who was eventually transferred to Germany, contacted me in January 2021 to inform me that his request for international protection had been rejected by the BAMF, the German authority responsible for granting asylum. His frustration was palpable: »They took us to deport us«, he told me bluntly. For him, seeing his friends from Messina successfully obtain asylum in France was especially frustrating. »If they knew in advance, why then take me?« (fieldnotes January 2021), he asked. His questions highlight a valid concern: Why select individuals from countries like Nigeria or Cameroon, whose chances of obtaining international protection are minimal, and where many are often deported? How do these practices align with the German government’s claim that »priority was given to people from countries with a high protection rate« (cf. Drucksache 19/22370), as well as to individuals with family ties to Germany or those considered vulnerable, when 89 percent of these individuals are ultimately rejected?

E. now lives in Germany under a Duldung permit, which restricts his ability to work or move to another town within the country (see Fontanari 2022b; 2022a; Schütze 2023). He has shifted from being detained in Italian camps to being confined in a small German city, with no clear path to regularise his status. This situation exemplifies a dual strategy. On the one hand, Germany participated in the Malta Agreement, showing southern EU states its willingness to take responsibility within a broader EU framework for migration management. On the other hand, the underlying logic behind the delegation’s decisions appears to be deportation.

This case highlights the logistical management of migration within the EU: redistribution based on a deportation logic. Migrants are registered, assessed, and evaluated, and then redistributed according to specific criteria. In this case, individuals with a higher likelihood of obtaining asylum were relocated to France, while those deemed ›economic migrants‹, and thus outside the victim-centred narrative of asylum, were sent to Germany to await rejection and deportation. This system underscores how asylum management has evolved into a logistical process that commodifies people, sorting them geographically and legally across different EU countries. Hotspots function as sites where EU member states can externalize asylum interviews before migrants even enter national territory, applying different procedures depending on the asylum seekers’ nationality and likelihood of obtaining protection.

From the Relocation procedure to the new EU Migration Pact

The institutionalisation of the procedures from the ad hoc relocations under the regulations of the new EU Migration Pact marks a pivotal moment in the evolution of the EU’s migration and asylum policies. Relocations are now formally integrated into the CEAS through the Asylum and Migration Management Regulation (cf. EU Commission 2024a), which introduces the Solidarity Mechanism. This mechanism, ostensibly designed to alleviate pressure on frontline Member States, builds on the 2018–2019 ad hoc relocation mechanism. It obliges EU Member States to share responsibility by relocating asylum seekers according to a predefined quota pool and specific national criteria.

However, unlike the earlier temporary relocation mechanism, the Solidarity Mechanism allows Member States to fulfil their obligations in alternative ways. Instead of relocating asylum seekers, states can provide logistical support for deportations under a system called ›return sponsorship‹. This approach enables Member States to assist in expediting the removal of migrants to third countries that have return agreements with the EU. If deportations are not completed within six months, relocation becomes mandatory. This dual option shifts the focus from purely redistributing asylum seekers to enforcing stricter deportation measures.

This flexibility mirrors Germany’s approach during the ad hoc relocation mechanisms, where it opted to relocate individuals only from designated safe third countries. In this way, this approach allowed Germany to externalise identification procedures at the external borders, pre-selecting individuals according to specific categories, while meeting its formal relocation quotas, showcasing ›solidarity‹ with southern Member States. The New Migration Pact exacerbates this process by allowing Germany to deport individuals directly from EU external border states to their countries of origin even when the EU member state involved—Italy, for example—does not have a formal readmission agreement with those countries, thereby bypassing established legal safeguards.

While the Solidarity Mechanism is framed as a collective effort to ease the burden on frontline states, in practice, it perpetuates the deterritorialisation of asylum. Migrants awaiting relocation will remain in southern hotspots, reinforcing the externalisation of border procedures. This shift aligns with the overarching strategy of the new EU Migration Pact, which emphasises control and efficiency at the expense of access to protection.

The Screening Regulation (cf. EU Commission 2024c) and the Asylum Procedures Regulation (cf. EU Commission 2024b) exacerbate this trend by transforming hotspots into extraterritorial zones. Centres located in places such as Lampedusa and Lesvos might be legally positioned outside the EU’s borders and therefore beyond the scope of many legal protections. This is achieved through the legal construct of the ›fiction of non-entry‹, whereby migrants arriving at hotspots are not considered to have entered EU territory. This status defers the lodging of asylum requests until the identification procedures are complete and admissibility decisions have been made. Admissibility will hinge on factors such as the applicant’s nationality, their likelihood of receiving protection based on recognition rates, and whether they transited through a designated ›safe third country‹.

The Commission asserts that asylum applications can be registered after the screening phase, but this framework creates significant obstacles for migrants seeking protection. The deferral of asylum processes limits migrants’ ability to effectively present their cases, often leaving them without access to legal representation or avenues for appeal. This system risks increasing errors in asylum decisions, including wrongful deportations. Moreover, prolonged detention during the screening and border procedures, combined with the opacity of the process, heightens the vulnerability of those deemed inadmissible.

The normalisation of hotspots as extraterritorial zones fundamentally alters their role within the EU’s migration framework. Campesi (2020) notes that hotspots are now institutionalised as standard components of the migration system, rebranded under terms like ›controlled centres‹ or ›transit zones‹. Officially responsible for identification, screening, and border procedures, these zones also facilitate the detention of so-called ›illegal‹ migrants. Positioned outside EU territory, these facilities limit the oversight necessary to prevent human rights violations or ensure procedural compliance.

Hotspots now function as logistical hubs, centralising asylum procedures while maintaining the quasi-detention status of migrants. Even after being accepted for relocation, migrants may still undergo asylum procedures within these facilities, as was observed during France’s participation in the relocation scheme. This entrenches a system where the majority of asylum processing occurs at external borders, in hotspot centres nowadays within the EU, but that might be considered extraterritorial and thus outside the EU when the new EU Migration Pact will be operationalised.

In effect, the new EU Migration Pact transforms hotspots into multi-functional detention and processing centres. Migrants face prolonged stays in these zones, often without clarity about their status or future. The Pact, by institutionalising these practices, prioritizes securitisation and logistical efficiency over humanitarian considerations. This evolution underscores the extent to which migration policy has become a tool for border control, increasingly divorced from the principles of protection and solidarity that underpin international asylum law.

Conclusion

In 2024, after many years of negotiations, the reform of the CEAS through the EU Pact on Migration and Asylum has been formalised and ratified. The pact includes mechanisms such as the mandatory solidarity requirement, stronger border controls, fast-track asylum procedures, and partnerships with third countries. It primarily prioritises control, efficiency, and the externalisation of border procedures to the external border (both within and outside the EU) at the expense of fundamental human rights.

The implementation of this Pact is reflective of a broader trend within EU migration policies that began with the 1985 Schengen Agreements, where ›irregular migration‹ was first criminalised and framed as a security issue. This historical context has led to the evolution of a highly logistical framework for managing asylum seekers and migrants, with concepts such as hotspots, hubs, and corridors that reduce migrants to units within an administrative system.

The Malta Agreements, implemented in 2019, foreshadowed many elements of the New Migration Pact, indicating continuity in the EU’s preference for operational efficiency over comprehensive protection of human rights. The empirical analysis of the temporary relocation mechanism, including the case studies of the Messina hotspot and the Crotone reception centre, illustrates the adverse impacts on migrants who face poor living conditions, prolonged uncertainty, and limited access to fundamental rights. The logistical emphasis on categorisation, containment, and efficiency often undermines the well-being of asylum seekers, revealing the limitations of an approach centred on control and regulation. The pilot project further reinforced a system that, while providing some redistribution, did not resolve the underlying tensions of the Dublin Regulation or adequately address the broader humanitarian needs of migrants.

The new EU Migration and Asylum Pact attempts to balance collective responsibility and enhance border security, but it underscores the inherent tension between logistical efficiency and the ethical obligation to uphold migrants’ rights. By transforming hotspots into multi-functional detention and processing centres and institutionalising practices that prioritise control, surveillance, and return mechanisms, the Pact reveals a migration regime increasingly focused on managing migrants as logistical entities rather than individuals in need of protection. Furthermore, the redefinition of hotspots as extraterritorial zones through the Screening and Asylum Procedures Regulations illustrates the EU’s increasing emphasis on externalising borders and deterring asylum claims.

For the EU to truly address the complexities of migration in a just and humane manner, it must reconsider the balance between security measures and the fundamental rights of individuals seeking asylum. The evolution of migration policy as a tool for border control undermines the principles of protection and solidarity that the EU has adopted as foundational values.

Literature

Alqamah (2020): Gli Inganni di Badia Grande, Alqamah of 09/09/2022. URL: alqamah.it [06.02.2025].

Altenried, Moritz (2017): Logistische Grenzlandschaften: Das Regime mobiler Arbeit nach dem Sommer der Migration. Münster.

Altenried, Moritz / Bojadžijev, Manuela / Höfler, Leif / Mezzadra, Sandro / Wallis, Mira (2018): Logistical Borderscapes: Politics and Mediation of Mobile Labor in Germany after the »Summer of Migration«. In: South Atlantic Quarterly 117 (2). 291–312.

Andersson, Ruben (2016): Europe’s Failed »Fight« against Irregular Migration: Ethnographic Notes on a Counterproductive Industry. In: Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42 (7). 1055–1075.

Ataç, Ilker / Steinhilper, Elias (2022): Arenas of Fragile Alliance Making. Space and Interaction in Precarious Migrant Protest in Berlin and Vienna. In: Social Movement Studies 21 (1–2). 152–168.

Bojadžijev, Manuela (2021): »The Spirit of Europe« Differential Migration, Labour and Logistification. In: Grappi, Giorgio (Ed.): Migration and the Contested Politics of Justice: Europe and the Global Dimension. London/New York.

Bojadžijev, Manuela / Karakayalı, Serhat (2007): Autonomie Der Migration. 10 Thesen Zu Einer Methode. In: TRANSIT MIGRATION Forschungsgruppe (Ed.): Turbulente Ränder. Biefeld, 203–210.

Borderline Sicilia / Sea Watch / Borderline Europe / Flüchtlingsrat Berlin / Equal Rights (2021): EU Ad Hoc Relocation: A Lottery from the Sea to the Hotspots and Back to Unsafety. URL: eu-relocation-watch.info [06.02.2025].

Bosswick, Wolfgang (2000): Development of Asylum Policy in Germany. In: Journal of Refugee Studies 13 (1). 43–60.

Bousiou, Alexandra / Papada, Evie (2020): Introducing the EC Hotspot Approach: A Framing Analysis of EU’s Most Authoritative Crisis Policy Response. In: International Migration 58. 139–152.

Brekke, Jan-Pauk / Brochmann, Grete. (2015): Stuck in Transit: Secondary Migration of Asylum Seekers in Europe, National Differences, and the Dublin Regulation. In: Journal of Refugee Studies 28 (2). 145–62.

Campesi, Giuseppe (2020): Normalizing the »Hotspot Approach«? An Analysis of the Commission’s Most Recent Proposals. In: Carrera, Sergio / Curtin, Deirdre / Geddes, Andrew (Eds.): 20 Year Anniversary of the Tampere Programme: Europeanisation Dynamics of the EU Area of Freedom, Security and Justice. European University Institute. Florence.

Campomori, Francesca / Ambrosini, Maurizio (2020): Multilevel Governance in Trouble: The Implementation of Asylum Seekers’ Reception in Italy as a Battleground. In: Comparative Migration Studies 8 (1). 1–22.

Casas-Cortes, Maribel / Cobarrubias, Sebastian / Heller, Charles / Pezzani, Lorenzo (2017): Clashing Cartographies, Migrating Maps: Mapping and the Politics of Mobility at the External Borders of E.U.rope. In: ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies 16 (1). 1–33.

Ceccorulli, Michela (2019): Back to Schengen: The Collective Securitisation of the EU Free-Border Area. In: West European Politics 42 (2). 302–322.

De Genova, Nicholas (2013): Spectacles of Migrant »Illegality«: The Scene of Exclusion, the Obscene of Inclusion. In: Ethnic and Racial Studies 36 (7). 1180–1198.

De Genova, Nicholas (Ed.) (2017): The Borders of »Europe«: Autonomy of Migration, Tactics of Bordering. Durham/London.

De Genova, Nicholas / Garelli, Glenda / Tazzioli, Martina (2018): Autonomy of Asylum? In: South Atlantic Quarterly 117 (2). 239–265.

De Landa, Manuel (2006): A New Philosophy of Society: Assemblage Theory and Social Complexity. London.

Della Porta, Donatella (2018a): Contentious Moves: Mobilising for Refugees’ Rights. In: Della Porta, Donatella (Ed.): Solidarity Mobilizations in the »Refugee Crisis«: Contentious Moves. Cham. 1–38.

Della Porta, Donatella (Ed.) (2018b): Solidarity Mobilizations in the »Refugee Crisis«: Contentious Moves. Cham.

Drucksache 19/22370: Kleine Anfrage der Abgeordneten Ulla Jelpke, Dr. André Hahn Gökay Akbulut, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion DIE LINKE. URL: dserver.bundestag.de [06.02.2025]

EASO (2019a): Note on the »Messina Model« Applied in the Context of Ad Hoc Relocation Arrangements Following Disembarkation. URL: reliefweb.int [06.02.2025].

EASO (2019b): Standard Operating Procedures for Ad-Hoc Relocation

Exercises.

URL: inlimine.asgi.it

[06.02.2025].

EU Commission (2024a): Regulation (EU) 2024/1351. Asylum and Migration Management Regulation.

EU Commission (2024b): Regulation (EU) 2024/1348. Asylum Procedure Regulation.

EU Commission (2024c): Regulation (EU) 2024/1356. Screening Regulation.

Eurostat (2019): Asylum Decisions in the EU. URL:ec.europa.eu [06.02.2025].

Fondebrider, Luis (2015): Forensic Anthropology and the Investigation of Political Violence: Lessons Learned from Latin America and the Balkans. In: Ferrándiz, Francisco J. / Robben, Antonius C. G. M. (Eds.): Necropolitics: Mass Graves and Exhumations in the Age of Human Rights. Philadelphia. 41–52.

Fontanari, Elena (2022a): Germany, Year 2020. The Tension between Asylum Right, Border Control, and Economy, through the Imperative of Deservingness. In: Migration Studies 10 (4). 766–788.

Fontanari, Elena (2022b): The Neoliberal Asylum. The Ausbildungsduldung in Germany: Rejected Asylum-Seekers Put to Work between Control and Integration. In: Sociologica 16(02). 117–147.

Garelli, Glenda / Tazzioli, Martina (2016): The EU Hotspot Approach at Lampedusa. Open Democracy of 26 February 2016. URL: opendemocracy.net [21.02.2025].

Grappi, Giorgio (2016): Logistica. Fondamenti. Roma.

Heck, Gerda / Hess, Sabine (2017): Tracing the Effects of the EU-Turkey Deal. In: movements. Journal for Critical Migration and Border Regime Studies 3 (2). 35–56.

Hess, Sabine / Kasparek, Bernd (2017): Under Control? Or Border (as) Conflict: Reflections on the European Border Regime. In: Social Inclusion 5 (3). 58–68.

Hess, Sabine / Kasparek, Bernd / Kron, Stefanie / Rodatz, Mathias / Schwertl, Maria / Sontowski, Simon (2017): Der lange Sommer der Migration. Berlin/Hamburg.

Høglund, Andreas (2017): The Implementation of the Dublin Regulations in Greece, Italy and Spain. Bergen.

Holmes, Seth M. / Castañeda, Heide (2016): Representing the »European Refugee Crisis« in Germany and Beyond: Deservingness and Difference, Life and Death. In: American Ethnologist 43 (1). 12–24.

Howard, Neil / Forin, Roberto (2019): Migrant Workers, »Modern Slavery« and the Politics of Representation in Italian Tomato Production. In: Economy and Society 48 (4). 579–601.

Il Post (2019): I ricollocamenti dei migranti caso per caso non funzionano. Il Post of 05.07.19 URL: ilpost.it [06.02.2025].

ISPI (2019): Migranti e Ue: cosa serve sapere sul vertice di Malta. ISPI of 20.09.2019. URL: ispionline.it [06.02.2025].

ISPI (2020a): Migrazioni in Italia: tutti i numeri. ISPI of 21.01.2020. URL: ispionline.it [06.02.2025].

ISPI (2020b): Migrazioni nel Mediterraneo: tutti i numeri. Text. ISPI of 21.01.2020. URL: ispionline.it [06.02.2025].

Juris, Jeffrey S. (2007): Practicing Militant Ethnography with the Movement for Global Resistance in Barcelona. In: Shukaitis Stevphen / Graeber David (Eds.): Constituent Imagination 13. Oakland/Edinburgh. 164–176.

Kasparek, Bernd (2016): Routes, Corridors, and Spaces of Exception: Governing Migration and Europe. In: Near Futures Online 1 (1), »Europe at a Crossroads«.

Krifors, Karin (2020): Logistics of Migrant Labour: Rethinking How Workers »Fit« Transnational Economies. In: Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (1). 1–18.

Longo, di Francesca (2002): Identità, sicurezza, frontiere. I paradigmi della lotta alla criminalità organizzata nell’Unione Europea. In: Meridiana 43. 135–158.

Meret, Susi / Aguiari, Irina (2020): Turning Migrants into Slaves: Labor Exploitation and Caporalato Practices in the Italian Agricultural Sector. In: Heinsen Johan / Jørgensen Martin Bak / Jørgensen Martin Ottovay (Eds.): Coercive Geographies: Historicizing Mobility, Labor and Confinement. Leiden. 102-123.

Mezzadra, Sandro (2017): Digital Mobility, Logistics, and the Politics of Migration. In: Spheres: Journal for Digital Cultures. 1–4.

Mezzadra, Sandro / Neilson, Brett (2013): Border as Method, or, the Multiplication of Labor. Durham.

Natter, Katharina (2023): What the EU-Tunisia Deal Reveals over Europe’s Migration Cooperation. In: Verfassungsblog of 05.09.2023. URL: hdl.handle.net [24.02.2025].

Pels, Peter (1997): The Anthropology of Colonialism: Culture, History, and the Emergence of Western Governmentality. In: Annual Review of Anthropology 26. 163–183.

Pels, Peter / Salemink, Oscar (1994): Introduction: Five Theses on Ethnography as Colonial Practice. In: History and Anthropology 8 (1–4). 1–34.

Perrotta, Domenico (2014): Ben Oltre Lo Sfruttamento: Lavorare Da Migranti in Agricoltura. In: Il Mulino. 63 (1). 29–37.

Picozza, Fiorenza (2021): The Coloniality of Asylum: Mobility, Autonomy and Solidarity in the Wake of Europe’s Refugee Crisis. Lanham.

Platania, Giuseppe (2021): Asylum Seekers’ Exploitation and Resistance. Evidence from Sicily. In: Reich, Hannah / Di Rosa, Roberta T. (Eds.): Newcomers as Agents for Social Change: Learning from the Italian Experience: A Recourse Book for Social Work and Social Work Education in the Field of Migration. Milano.

Pollozek, Silvan / Passoth, Jan Hendrik (2019): Infrastructuring European Migration and Border Control: The Logistics of Registration and Identification at Moria Hotspot. In: Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 37 (4). 606–624.

Scheel, Stephan (2018): Real Fake? Appropriating Mobility via Schengen Visa in the Context of Biometric Border Controls. In: Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (16). 2747–2763.

Scheel, Stephan (2019): Autonomy of Migration?: Appropriating Mobility within Biometric Border Regimes. Abingdon, Oxon/New York.

Scheper-Hughes, Nancy (1995): The Primacy of the Ethical: Propositions for a Militant Anthropology. In: Current Anthropology 36 (3). 409–440.

Schütze, Theresa (2023): The (Non-)Status of »Duldung«: Non-Deportability in Germany and the Politics of Limitless Temporariness. In: Journal of Refugee Studies 36 (3). 409–429.

Squire, Vicki (2009): The Exclusionary Politics of Asylum. London.

Stille, Alexander (2018): How Matteo Salvini Pulled Italy to the Far Right. The Guardian of 09.08.2018. URL: theguardian.com [06.02.2025].

Tazzioli, Martina (2018): Containment through Mobility: Migrants’ Spatial Disobediences and the Reshaping of Control through the Hotspot System. In: Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (16). 2764–2779.

Tazzioli, Martina (2020): Governing Migrant Mobility through Mobility: Containment and Dispersal at the Internal Frontiers of Europe. In: Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 38 (1). 3–19.

Vari, Elisa (2020): Italy-Libya Memorandum of Understanding Italy’s International Obligations. In: Hastings International and Comparative Law Review 43 (1). 105–134.

Vianelli, Lorenzo (2017): Governing Asylum Seekers: Logistics, Differentiation, and Failure in the European Union’s Reception Regime. Warwick.

Vianelli, Lorenzo (2022): Warehousing Asylum Seekers: The Logistification of Reception. In: Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 40 (1). 41–59.

Walters, William (2002): Mapping Schengenland: Denaturalizing the Border. In: Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 20 (5). 561–580.

Xiang, Biao / Lindquist, Johan (2014): Migration Infrastructure. In: International Migration Review 48 (S1). S122–S148.

This paper is part of a broader research project conducted in collaboration with Borderline Sicilia, Borderline Europe, Equal Rights, Flüchtlingsrat Berlin, and Sea-Watch, culminating in a report that denounces the practices implemented in Italy, Malta, and Germany during the relocation mechanism (see Borderline Sicilia et al. 2021).↩︎

see Bojadžijev/Karakayalı 2007; Squire 2009; Andersson 2016; Tazzioli 2020; Picozza 2021; De Genova et al. 2021.↩︎