Abstract Over the last few decades, the UK has implemented an increasingly strict and inhumane immigration system aimed at creating a Hostile Environment for those deemed illegal or undeserving migrants. This creative piece consists of a selection of texts and artwork co-created by a group of migrant women activists from London over a residential weekend of creative research workshops in August 2023. The women reflect on their experiences with the slow violence and everyday bordering of the Hostile Environment, specifically the no recourse to public funds (NRPF) policy. At the same time, the contributions highlight the power of collective resistance, solidarity, and community building through story-telling and co-creative practices. (This work is part of an ongoing research project by the author as part of her PhD studies.)

Keywords UK hostile environment, no recourse to public funds (NRPF), migrant women’s resistance, creative storytelling, participatory methodology

This contribution comprises a selection of texts and artwork from a series of co-creative workshops with a group of migrant women1 activists, as part of a residential trip to Dorset, UK in the summer of 2023. The storytellers and artists contributing to this project are a diverse group of migrants from London; most of them had already known each other for several years through being active community leaders and members of the former South London Refugee Association’s Women Group who were a project partner for this collaborative research project. The collaborators and storytellers of this project were (in alphabetical order): Agnes, Amanda, Fahmida, Faiza, Fatima, Florence, Mary, Mavis, Olukemi, Rozaline.

All the women in the group have had some, albeit different, experiences of the UK’s Hostile Environment policies towards migrants and having ›no recourse to public funds‹ (NRPF). The term Hostile Environment is based on a 2012 quote by the then Home Secretary Theresa May who said in an interview with the Telegraph that the new Immigration Act at the time was aimed to create a »hostile environment for illegal immigration« (Kirkup/Winnett 2012). The phrase has since become an umbrella term for the UK’s steadily expanding inhumane immigration legislation, administration, practice, and discourse.

NRPF refers to an immigration policy which denies people access to statutory support based on their immigration status, e.g., welfare, housing, or child benefits. It applies to migrants with limited or no leave to remain (immigration status) in the UK and affects an estimated 3.26 million people, including over half a million children (Pinter/Leon 2025)2. NRPF disproportionately pushes Black, female, single carers into destitution (ibid.) and can therefore be understood as a key mechanism contributing to the precarisation of racialised life in the UK (Smith et al. 2021). While there is a well-established body of critical migration scholarship which has analysed how hierarchies of deservedness within humanitarian protection regimes are deeply classed, racialised, and gendered (see De Genova 2013; Bassel/Emejulu 2018), many aspects of the UK’s Hostile Environment remain overlooked. This is particularly the case with issues such as NRPF and the increasingly expensive and long routes to settlement, which impact low-income and negatively racialised migrants struggling for survival outside the refugee/asylum framework, and which continue to be alarmingly invisibilised in public, political, and academic discussions.

While there can be a sense of urgency to ›tell the stories‹ of this invisibilised injustice, it is important to be cautious of the inherent risk of reproducing that same violence in the project of ›uncovering‹ or ›evidencing‹ it. Eve Tuck (2009) writes about this as the danger of »damage-focused research« which by retelling the damage done to certain ›oppressed communities‹ reinforces their supposed »brokenness« (Tuck 2009: 413). In the context of border(ing) violence, this is particularly pertinent with migrants and refugees being forced to ›tell their stories‹ over and over again—to Home Office employees, social workers, judges, and so on—to prove their deservedness and ultimately, their humanness. Alexandra D’Onofrio (2019) argues how creative methodologies are becoming an emerging tool within migration studies to avoid getting caught in such a »testimony trap« present in the linear retelling of (past) journeys and violences. The imaginative and collaborative aspects of creative practice can be a way to reflect on the »imaginary realm of migration« (Sjöberg/D’Onofrio 2020: 2) within contexts of im/mobility in more fluid ways. Creativity is something that can help communities to engage with »the not yet and, at times, the not anymore« (Tuck 2009: 417) and not only imagine but begin to practice new states of being together.

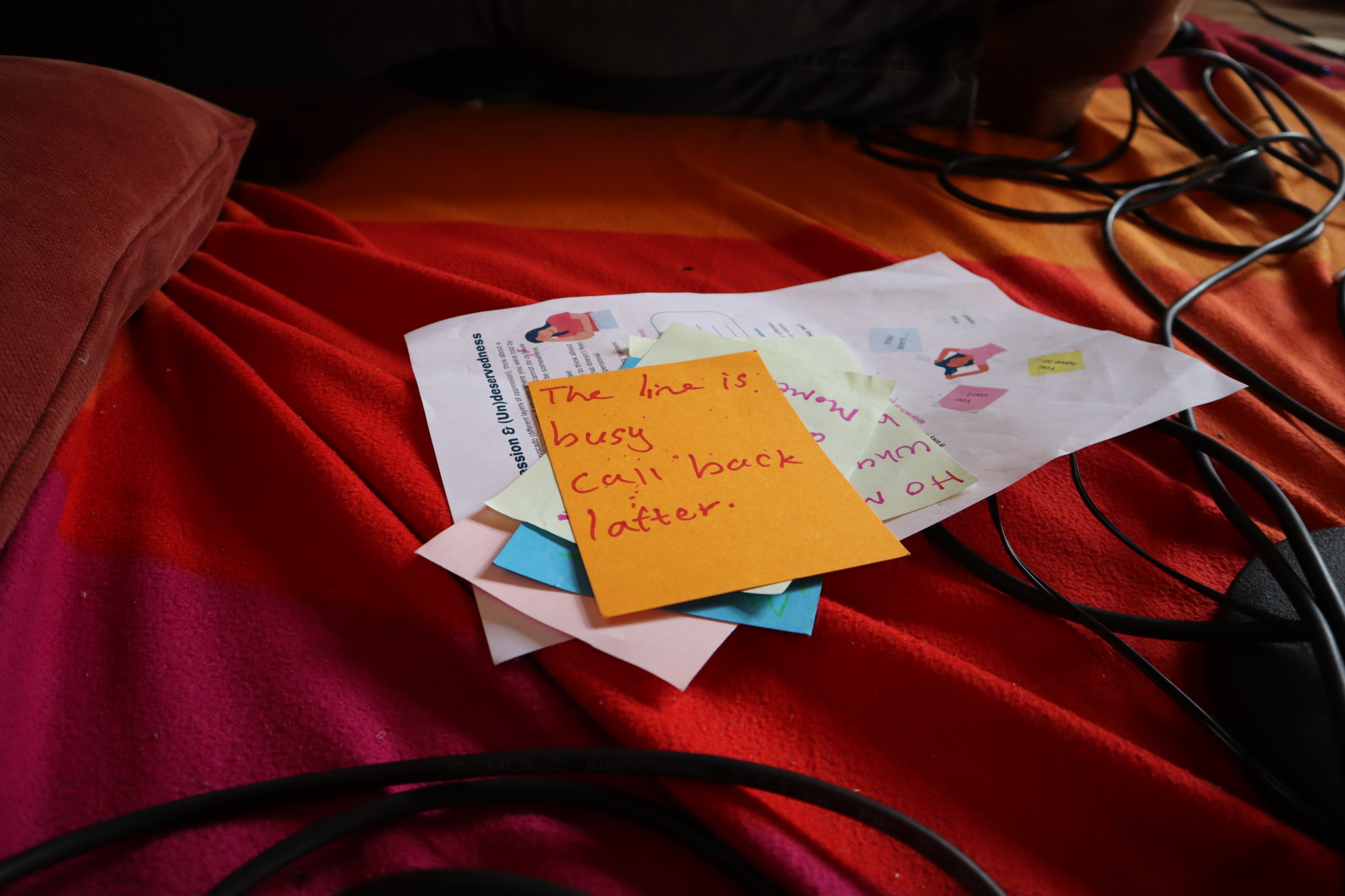

Based on these concepts of a critical creative research practice, this contribution is conceived as a playful experiment to re-claim storytelling within the context of the Hostile Environment. Through a selection of text fragments and photographs from our workshops, we—the researcher and collaborators—are trying to tell stories differently, not to prove anything or to provide evidence, but instead, we tell stories to create connections with each other, to make us feel that we are not alone, to build solidarity, to imagine alternative futures, and to take collective action.

Crafting Knowledges: Collaborative, Creative, Embodied Methods

The sessions this contribution is based on took place during a residential weekend in the summer of 2023 at the Monkton Wyld Court farm, an environmental and educational community organisation in Dorset, UK. The idea behind the residential trip was to offer a caring and nurturing space away from the stress of everyday responsibilities to engage in a collective creative process and reflection on the collaborator’s experiences of surviving and resisting the Hostile Environment. This contribution aims to document and share insights of our creative process together, and in so doing offers a critical intervention around participatory and arts-based research methods. Central to this approach was the idea of collaboration. Thinking, making, and learning together, in community and connection with each other, is something that has a long tradition within women’s organising. Black feminists in particular have emphasised the need to produce, test, and affirm knowledges, ideas and actions for positive change, not in isolation but in ›dialogue‹ (Collins 2000) and ›negotiation‹ (Nnaemeka 2004) with each other. As one of the contributors, Amanda, pointed out »all along this journey of this weekend has been about learning and getting to know different things«.

The workshops consisted of various different creative activities and open conversations. We started with discussions on different concepts such as ›slow violence‹ (Nixon 2011), ›everyday bordering‹ (Yuval-Davis et al. 2018), a decolonial critique of the UK border regime (see El-Enany 2020), and the various levels and sites of oppression the members of the group experienced. Through a series of embodied and material practices, we then engaged not only with the topic of violence but at the same time the resistance to it and how we can continue to build communities of solidarity and care. In many of the activities, we made use of our bodies and voices through songwriting and sound-making and layering different voices with a loop station3. As the workshop took place on an organic farm with beautiful gardens and outdoor space, another focus of our activities was the engagement with the natural environment and material around us. The following is an example instruction of one of our activities:

Community Walk

Walk in pairs and have a conversation about:

community // care // support networks // resistance

While you are walking, collect some objects (about 5) from the nature or your surroundings, anything you feel drawn to.

Record your walk in creative ways (you can record the audio of your conversation on your phone, you can take some photos and videos of yourself and the space).

Conversation Prompts

What and who has helped you through your journey through the Hostile Environment?

What and who mean ›community‹ for you?

What gives you hope and strength?

What does ›resistance‹ mean to you?

With the objects that had been collected during these activities, the collaborators created small installations which then, in turn, triggered new reflections and conversations in the group. Throughout the weekend, everyone crafted a small box for which they individually chose some objects, notes, and artwork that inspired them or represented some learnings from our sessions. The group would later name these boxes »pockets of togetherness« and they became a form of collective »counter-archives of resistance« (Calderón Harker 2024).

Our engagement not only with each other but also with the space, the material, and nature around us was deeply collaborative and relational. Through collaboratively crafting stories and knowledges, we included embodied and multi-sensual ways of knowing beyond words in an ongoing process of collective learning. This can be a radical act of reclaiming (academic) knowledge and theory and re-mattering it, breathe life into it or as Nnaemeka (2004: 363) says »put a human face on what is called a body of knowledge«:

»Like other so-called marginal discourses, feminist discourse raises crucial questions about knowledge not only as being but as becoming, not only as a construct but as a construction, not only as a product but as a process. In other words, knowledge as a process is a crucial part of knowledge as a product. By injecting issues of subjectivity and location into epistemological debates, feminist scholarship seeks, as it were, to put a human face on what is called a body of knowledge and in the process unmasks this presumably faceless body. By focusing on methodology (and sometimes intent), feminist scholarship brings up for scrutiny the human agency implicated in knowledge formation and information management.« (Ibid.)

Academic theories on migration are based on people’s stories, lives, and bodies on which the ›necropolitics‹ (Mbembe 2019) of the borders have left their deep marks. Where academia might have removed these very bodies from its theories, our creative and inter-connected practices have re-invited matter, bodies, and voices into the room to inter-act, experiment and learn together. Creative and embodied practice not only enhances and advances theory but, in fact represents a form of theory itself—knowing and theorising »as a verb« (Nnaemeka, 2004: 365). To centre theorising through lived and embodied knowledges means to also rethink and trouble the format of academic publications and authorship. Reducing the knowledge of ›research participants‹ to ›qualitative data‹ which then becomes interpreted, abstracted, and represented by the researcher, risks cementing hierarchical relations of the researcher as the knower and the researched as the known. This contribution therefore is also an attempt to allow ›research participants‹ to reclaim the space of academic publications as authors, storytellers, knowledge bearers, as experts and theorists themselves.

The following texts are entirely based on the transcripts of audio recordings of our sessions together. This meant adapting the format from spoken to written text, and whilst I have tried to remain close to the original wording, it is important to recognise that there still have been choices around editing and importantly selection and curation made by myself, as well as including input by the movement editors. Throughout this process, I have tried to engage in an ongoing conversation with the collaborators whilst being responsive to their availabilities and preferences. This meant that some collaborators simply confirmed my suggested edits, whilst others chose to be more actively involved in re-editing their transcript for this publication. With regard to authorship, I asked the collaborators to choose whether they would like to use their full names, but all of them preferred to only include their first name. The selection of texts and artwork in this contribution is only a smaller selection of a longer documentation, which is available as a printed or online zine on my website4.

Stories of Dis/connections and In/dependence, Solidarity, and Care

Sometimes, the violence of the Hostile Environment and especially of NRPF can be slow and hardly visible to the outsider. It can mean living in insecure and unsafe housing, living a life in poverty, years of insecurity and waiting in a legal limbo. Borders filter through all aspects of everyday lives for those who are legally ›subject to immigration control‹. The following stories talk about life within and against this »slow violence« (Nixon 2011) of the Hostile Environment, and about transient connections within disconnecting systems and worlds. They show us how our environment and nature can be a teacher and inspiration to understand and tell stories about our lives. They talk of change, imagination, and desire, of community, of hope and solidarity—across generations, and even across species.

As the Hostile Environment’s violence is happening in the everyday, it is difficult to pin down, describe, see, hear, witness, as is the resistance against it. As Florence writes, we can »never block all the holes«, but neither can the state’s borders block them all. And so, we continue to survive, to witness, to tell and listen to stories, to resist in those holes and cracks. I want to invite you to read the following stories as a prompt to reflect on what such slow resistance might feel like. How might we begin to change systems, people, laws, experiences, relationships, or thoughts? Does change happen through words, connections, or actions? One thing our stories suggest for sure—change happens in togetherness!

Wherever the Wind Blows Them (Fahmida)

»The small brown seeds, I don’t know if you see them, here on the paper, they’re really thin. They usually fly with the wind and if they find moisture and arrive in a suitable environment, they grow. We hear a lot of things they say about the immigrants, they’re coming in boats, they just try to enter the country, they just want to take the jobs, they just want to get the free money, they want to get the benefit, they’re all going like this. These seeds, they don’t decide their fate, they depend on the wind, wherever the wind blows them, which direction. They can burn, they can die, or they can grow, they don’t know what’s going to happen. Same with those people who are coming in the ship, they don’t know if they’re going to make it. Few days ago, a boat sank with the people, and they all died, no-one survived. They don’t make their fate; it’s not in their hands. There are circumstances that make them like these seeds, just flown and pushed by the wind, going wherever…«

»And there are people like that nail, the big nail, I picked up. How long you leave it there, it’s going to get rotten and when it’s getting old, it’s getting rusted. It turns into a kind of poison, it’s going to cause more damage, and it’s not going to help us thrive. It’s never going to dissolve, and it’s never going to become whole again. You leave it in the air, with the sand, no matter how much the environment tries to absorb this nail, it’s never going to become a part of it, because it’s stubborn, it wants to stay that way.«

How Am I Gonna Block All These Holes? (Florence)

»Not having your immigration status is like your life becomes a basket with many holes. You ask yourself, how am I going to block all these holes!! It’s like when you’re trying to block one hole, another hole is waiting for you. You just can’t block them all, no matter how hard you try, the water is still going through.

You just can’t!

After you’ve gotten your immigration status sorted out, that’s just one hole you managed to block, but remember the basket has many holes. Housing, employment, college, and many more holes that you can’t just block easily and move on! It’s hard… At the end of the day, you say to yourself, oh my days, I thought that after I’ve had my status, everything is sorted, because that’s what we’ve always had in mind, right? When your status is given to you, oh my days, you’re excited. But then you go on applying for housing, because you can’t afford private rent, then housing officer says to you, you’re not homeless, you don’t have a child, for these reasons, you don’t qualify. And you ask yourself this question again:

How am I gonna block all these holes? What am I going to do? I’ve gotten my status but…

Putting things in place to start a new life becomes even harder, because most of the organisations you ask for help say you’re not qualified any more because you now have immigration status. It is like the same thing you went through with the immigration comes back to play in your life again.

You just can’t block them all.

The same way you fight to get your status, the same way you are going to fight to block some of the other holes that stand between you and the important things in your life, trying to get a house, a job, and many many other things.

You go through a lot to get your settlement as an immigrant. It’s like a cycle that you can’t do anything about.

It’s a cycle of pain.«

The Season of a Flower (Florence and Mavis)

Florence: »The flower has a season. When the sun touches, they grow up and will come out bright like this. And sometime in a while, it will just go…«

Mavis: »… if you don’t take care of it…«

Florence: »Yeah, if you don’t take care of it or… even if you take care of it, they have their season. There are people who come when you need them, friends, family. When people feel pity for you, at the ease of the moment, they say, »don’t worry, I’m here for you, anything you want«. After some time, they get tired, they’re like, »oh my god«, when they see your call, they just ignore it, they’re gonna say, »I know what she’s gonna ask me, she’s gonna ask me to help her, I got my own problems«. So, at the end of the day, you don’t hear from them any more, they don’t pick your call, they keep fading their way. There are people in our lives that have their season to help us, their time. They will help you, after that, they will just disappear, it’s just like that flower…

Mavis: »…which is OK…«

Florence: »…which is OK…«

This Is a Snail Shell: Building Blocks of Something Extraordinary (Fahmida)

»In this group, we are a community, building blocks of something. When you start making something, you start from somewhere. I see all of us as a pillar of something new which is going to come, and it’s going to be extraordinary. Maybe, we are not there to see it, maybe we are in the middle of it, or maybe we started that structure. Because I see how each of us has grown and changed over time. If I try to remember those meetings, when we used to see each other, and how we came together in lockdown, when everything slowed down, and we had that bright light—some enjoyment in our group. And today we are here as a group. Did you ever imagine you’re going to travel with some women you never met before? Women from all different walks of life, and you’re loving their company, you’re enjoying them, you’re singing with them, you’re eating with them, you’re having fun. And you are all the way far from your original home, you come to a new place with some totally new experiences and things to see. And all of this, it’s still making something good afterwards.«

»This is a snail shell. When I was young, I used to collect them a lot because they used to make the walls out of mud, and you can see the shells in the walls. This one has a different colour because the climate is different here. There they are usually grey and whitish. Usually when snails grow out, they leave their shell behind for some other insect who can use it as their home. This is kind of a nice gesture of them to help someone else.«

We Can Be a Support For Each Other and Start From There (Olukemi)

»I just want everyone to think of…

Because a bigger group started from somewhere, from two, from three, from four, before they started looking like something and get known. As women, we can be active, positive, and so supportive to the community. What can we do together to help others? Let’s think about that. From there, we can start our organisation.

We can be a support for each other even in this place, we can actually start from there. If we know how to support each other in this minimal group, then we will learn how to support in a bigger way. Because if I can render you the support you need now, it means that I’m reliable for anybody out there, you understand? If I know that within us, we have satisfied each other, everybody here, we are ok, then we can go outside and achieve whatever project we got. I think, if we start with that, to be a support system for each other first, that is how we can grow stronger together. That’s my own suggestion, I don’t know if it goes fine with everybody.«

We Don’t Let Life Weigh Us Down (Rozaline)

»You can’t give what you don’t have. When I’m in a happy mood, I will come to you smiling and calmly; when I’m upset, you won’t even want to be next to me because of my facial expression. If someone is angry, you can’t expect that person to smile at you, because I’m not happy, I’m upset. But we don’t let life weigh us down.

We are all different, but I tell people, nobody can make you happy, only you can make yourself happy. Don’t let your environment put you down, most especially when you have a kid; even if you don’t have a kid, be strong for yourself. The situations we find ourselves in can make us feel down and depressed but remind yourself that this is just a journey, and I’m going to come out of it one day.

In the hostel [temporary accommodation] where I live, there are people who are always depressed, they ask themselves, when are they going to move and all that. I just make it comfortable for my kids, because the moment I keep on thinking about it, I can’t… It’s something that you don’t have power over. What are you going to do? You can’t do anything because you don’t have the power over it. The only thing you can do is make your own best moment for yourself, make yourself happy because nobody else can. That’s what I believe in.

What she carries, she gives around. What we are going through affects the people around us. Sometimes we might push our loved ones away with our attitude; someone might want to help you, but the moment this person sits down, and you’re upset and angry, they wouldn’t want to come near you, they will go away. So, just try! I use myself as an example, no matter what I’m going through, you never see me with a squeezed face because I left that behind, I might go back to it, but I want to be in a happy mood, so that people can help me. The moment I’m happy, that’s when I’m able to share my thoughts or whatever I’m going through with you. But when I’m sad, and you see this sad face, you will say, let me stay away from her, I don’t want problems, do you understand? So, we don’t let our problems weigh us down, let us be victorious.«

Concluding Reflections

The stories in this contribution have shared lived experiences of struggle and survival, as well as solidarity and community within and beyond the UK’s border regime. Through experimenting with the narrative format, I have tried to challenge victimising and »damage-focused« (Tuck 2009) representations of migrant narratives; I have applied an assemblage of photographs and text fragments based on audio transcripts from a collaborative workshop setting, juxtaposed with my own reflections on the process. Katherine McKittrick (2021) writes how storytelling has the potential to disrupt the colonial logic of description, categorisation and of ›finding solutions‹: »the story has no answer [… instead] stories offer an aesthetic relationality that relies on the dynamics of creating-narrating-listening-hearing-reading-and-sometimes-unhearing« (ibid: 5). Similarly, the material shared in this contribution remains unfixed, at least to a certain extent; it continues to invite processes of collaborative thinking, of »knowing as a verb« (Nnaemeka 2004) by carrying different meanings and messages for different readers. The documentation and insights of our aesthetic practice during the workshops illustrate how arts-based methods can be a powerful tool for collective storytelling, using creativity to help communities imagine and craft alternative ways of being. As Augusto Boal said, theatre can be a »rehearsal for the revolution« (Boal 2008: 119), as can music and other artforms.5 Within collaborative, creative processes, together we rehearse, we train our muscles of imagination to start to think about what a world without borders could look like, how we could be with each other if we all had the same rights, if we were all safe. Therefore, offering a nurturing and safer space for the research sessions to take place in has been a crucial aspect of this project—co-creating a caring environment as antidote to the Hostile Environment by the British state. The world in its current state is fundamentally unjust, Europe’s deadly immigration policies won’t change tomorrow. So, then maybe all we can do is try to create in the here and now a world, a space, a moment, a story between ourselves that is a little more hopeful—a ›pocket of togetherness‹. In this contribution, and in my practice more generally, I am wondering and critically exploring if and how academic research can offer such a moment or ›pocket‹ of caring, connecting and imagining—research as a creative and care-full intervention.

Credits, Further Information and Support

Partner Organisations: South London Refugee Association and Monkton Wyld Court.

Funding: The residential was funded by the Open Society University Network (OSUN) Engaged Research Fund. Rebekka Hölzle has received funding by the UK Economic and Social Research Council for her doctoral studies.

If you would like to find out more about the project and download the full zine with more texts and artwork by the group, or get in touch about collaborations, please visit Rebekka Hölzle’s website: www.rebekka-hoelzle.org

Thank you to all the women collaborating on the project and sharing their stories and wisdom. Thank you to the SLRA and Monkton staff for their support and especially also to the childcare team, Andy, Hamid, Hayat, Lisa, Sasha, Tamara, without whom the project would not have been possible.

If you would like to support the much-needed work of migrant and refugee community organisations on the ground, consider a donation to the project partner South London Refugee Association. You can find out more about their work here: www.slr-a.org.uk

Literature

Bassel, Leah / Emejulu, Akwugo (2018): Caring subjects: Migrant women and the third sector in England and Scotland. In: Ethnic and Racial Studies 41(1). 36–54.

Boal, Augusto (2008): Theatre of the Oppressed. 3rd ed. London.

Calderón Harker, Sergio (2024): Border Abolitionism as Method: Engaging with Counter-archives of Resistance in and against Europe’s Detention Regime. Society for Cultural Anthropology Blog of 13.02.2024. Series ›Relating, Refusing, and Archiving Otherwise‹, URL: culanth.org [16.05.2024].

Collins, Patricia Hill (2000): Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. 2nd edition. New York.

Connor, Phillip / Passel, Jeffrey S. (2019): Europe’s unauthorized immigrant population peaks in 2016, then levels off. The Pew Research Centre. URL : pewresearch.org [29.08.2024].

De Genova, Nicholas (2013): Spectacles of migrant ›illegality‹: The scene of exclusion, the obscene of inclusion. In: Ethnic and Racial Studies 36 (7). 1180–1198.

D’Onofrio, Alexandra (2019): Performing im/mobility: Going beyond the testimony trap. In: Performing Ethos: International Journal of Ethics in Theatre & Performance 9 (1). 83–89.

El-Enany, Nadine (2020): (B)ordering Britain: Law, Race and Empire. Manchester.

Harman, Kerry (2021): Sensory ways of knowing care: Possibilities for reconfiguring ›the distribution of the sensible‹ in paid homecare work. In: International Journal of Care and Caring 5 (3). 433–446.

Kirkup, James / Winnett, Robert (2012): Theresa May interview: ›We’re going to give illegal migrants a really hostile reception‹. The Telegraph of 25.05.2012 [online]. URL: telegraph.co.uk [16.05.2024].

Mbembe, Achille (2019): Necropolitics. Durham, NC.

McKittrick, Katherine (2021): Dear Science and Other Stories. Durham, NC.

Nixon, Rob (2011): Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Cambridge, MA.

Nnaemeka, Obioma (2004): Nego-feminism: Theorizing, practicing, and pruning Africa’s way. In: Signs. Journal of Women in Culture and Society 29 (2). 357–385.

Pinter, Ilona / Leon, Lucy (2025): Evidence briefing: Poverty among children affected by UK government asylum and immigration policy. Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion (CASE), London School of Economics and Political Science & Centre on Migration, Policy and Society (COMPAS), University of Oxford. URL: compas.ox.ac.uk [20.02.2025].

Sjöberg, Johannes / D’Onofrio, Alexandra (2020): Moving global horizons: Imagining selfhood, mobility and futurities through creative practice in ethnographic research. In: Culture & Psychology 26 (4). 732–748.

Smith, Charles / O’Reilly, Papatya / Rumpel, Rebekka / White, Rachel (2021). How do I survive now? The impact of living with No Recourse to Public Funds. Citizens Advice report. URL: citizensadvice.org.uk [16.05.2024].

Tuck, Eve (2009): Suspending Damage: A Letter to Communities. In: Harvard Educational Review 79 (3). 409–427.

Yuval-Davis, Nira / Wemyss, Georgie / Cassidy, Kathryn (2018): Everyday Bordering, Belonging and the Reorientation of British Immigration Legislation. In: Sociology, 52 (2). 228–244.

I define ›women‹ in this text as anyone who self-identifies as a woman or female, regardless of ascribed biological sex. This definition implies shared, albeit intersectionally differentiated experiences of patriarchal oppression. The South London Refugee Association’s Women Group has been open to anyone self-identifying with this description and wishing to interact in a welcoming ›women-only‹ space, inclusive of trans or non-binary people.↩︎

This number of 3.26 million is based on a 2025 report by the Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion (CASE), London School of Economics and Political Science & Centre on Migration, Policy and Society (COMPAS), University of Oxford (Pinter/Leon, 2025), refers to anyone with a valid leave to remain or a visa allowing them to reside in the UK, which generally comes with an NRPF condition. This estimate does not include migrants without valid immigration status. A 2019 report by the Pew Research Centre suggests the number of undocumented migrants in the UK to be between 800,000 and 1.2 million (Connor/Passel, 2019), however estimates vary greatly.↩︎

On my website (www.rebekka-hoelzle.org) you can listen to examples of audio material from our workshops.↩︎

Available on www.rebekka-hoelzle.org↩︎

See Augusto Boal’s work on the ›theatre of the oppressed‹ (see Boal 2008).↩︎