Abstract A collection of fragments titled The Shining: From an Anonymous Wall to Madina Hussiny Square assembles artist statements and descriptions of an ongoing series of site-specific interventions in Zagreb made of heat sheet and white masking tape as well as the author’s personal notes on the brief but thought-provoking encounters with Y., H. and K. The ›light‹ interventions in conjunction with the powerful migrant stories speak of fragmented, incomplete, and unfinished struggles and display disrupted narratives. Performed and written in solidarity with all the incarcerated and in memory of all the deceased.

Keywords Balkan corridor, Balkan route, site-specific interventions, heat sheet, freedom of movement

Everything emerges and submerges in the same place: in the (un)inhabited ›squares‹ of soil. But in order to foster a community, merely building a ›settlement‹ is not enough. Because once settled, though physically living almost conjoined, we are rarely together. And even when miles and continents separate us, our entire fabric of being co-exists simultaneously. If we were to simply stop at any coordinate along this mega-narrative and look at the world long enough, we would recognize our own contours emerging from this global tapestry.

Here, coexistence is implied, but our relationships often do not develop spontaneously, organically, or through shared experiences. And while the political, social and economical conditions for the organization of life are extremely simplified, and the communities worldwide are systemically impoverished and artificially parceled, the gap becomes almost insurmountable. The attempt to reestablish the connectivity seems in vain, even structurally impossible.

We have confined ourselves to walls, boundaries, property, and profit. Radical connections are undesirable, and subverting ›the structure‹ is strictly forbidden, rendering us permanently ›unavailable‹ for the global uprising—powerless in our collective ›shining‹.

The neighborhood of Folnegovićevo naselje in Zagreb is one of many post-Second World War modernist settlements in Europe. Through a closer study of the local imprint, this neighborhood reveals a ›conflict map‹ representing global phenomena reaching from a planned settlement that indirectly includes a class division, a post-socialist period of privatization and urban deindustrialization, a neighborhood antagonism concerning ethnic origins and the class affiliations of its settlers up to the history of migration and refugeeism related to ongoing wars, global economy, and geopolitics.

The Shining (2017),1 a temporary intervention on the surface of a social housing façade in Folnegovićevo naselje, attempted to establish a connection between the various inhabitants of the modernist buildings (the prefab ›tin-can‹ housing units built in the 1960s that require urgent solutions for both their dampness and dilapidation as well as a ›remedy‹ for the class divisions between the co-owners), phenomena related to refugees that have left traces throughout the neighborhood’s recent history (from the post-Yugoslav Wars, the Arab Spring up to the Balkan corridor-period), and the collateral scars of the global capitalist war (with its Croatian involvement in the global arms trade and war industry). With such a complex patchwork at hand, this symbolic act of shining from an anonymous, porous wall incites us to devise political imagination beyond obedience and to produce resistive practices, reflected in the global struggles for justice and equity.

I met Y. at Zagreb Central Station in February 2016, just before the closure of the so-called Balkan corridor.2 We have remained in contact since. He was traveling from Morocco with three other friends and was forced to continue the journey forward. To this day, Y. has not ›settled‹ in his new country of residence—and it is still questionable if he ever will. The repressive and racist European migration regime has made him a modern-day slave—forcing him to survive on 20 euros a day, picking apples on fruit plantations in the north of Italy. There, he joined a workforce of tens if not hundreds of thousands of voiceless migrant workers, abused and exploited for private profit by the large economies.

During the peak of the so-called refugee crisis in Croatia, the general populous kept calm. They continued buying ›Italian‹ fruits at supermarkets throughout the country, and apples handpicked by Y. easily found their way to our family tables.

To call those affected by war, poverty, or climate change ›a (refugee/migrant) crisis‹ deliberately misleads us from the core causes of contemporary migration and obscures the importance of fundamental human rights: freedom of movement and our unconditional right to choose where we want to settle down. I believe each person should be able to move as freely as I do and to be able to choose a home as I did. Why was Y. denied that right?

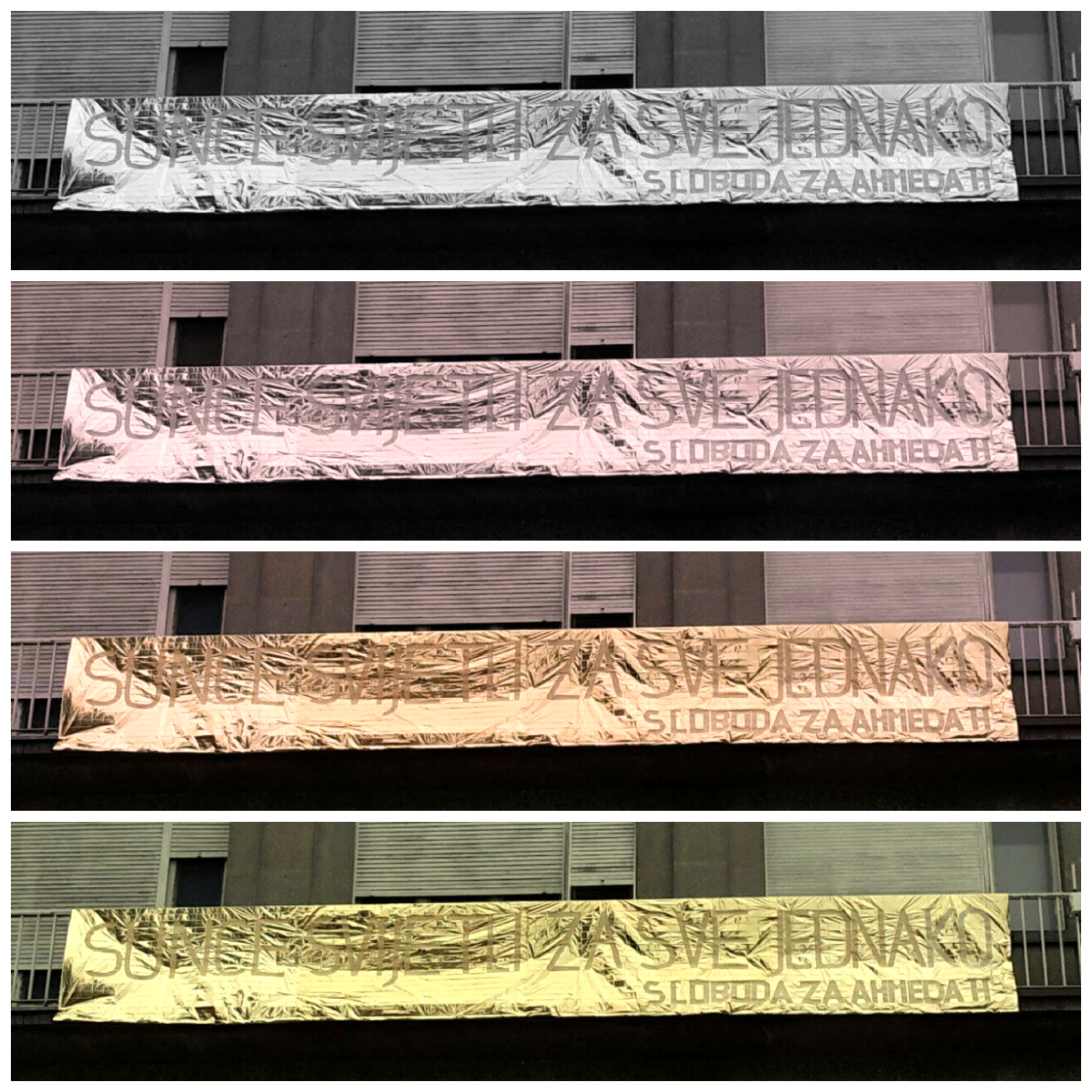

The Sun Shines Equally for All (2018),3 is a collaborative trans-action whose aim was to express comradeship and transnational solidarity with Ahmed H.,4 Röszke 11 and campaign activists, political prisoners, and detained migrants in Hungary and beyond. Golden during the day and black during the night, the banner displayed on Zagreb’s main square demanded the immediate release of Ahmed and all other prisoners held by the racist, neo-colonial ›fortress‹ of Europe. The symbolic act of the heat sheet shining on Zagreb’s main square sent a powerful message to the ›fortress‹ rulers: you can not rule what is ungovernable.

Some days ago, I posted a status: »Sorelle e fratelli uniti, fanculo al razzismo e al capitalismo«, with a link to an Italian rap song telling the story of a boy forced to cross the Mediterranean sea in a »death boat«. H., who himself undertook that journey, replied within minutes with a sequence of emoticons: thinking face emoji, green heart, red heart, and a power fist. He wanted to cheer me up. As if I was the one forced to take that journey next. H.’s gesture reminded me of K.’s question.

I met K. at Zagreb Central Station in March 2019, during the intensified period of violent police push-backs from Croatia to Bosnia. He walked for thirteen days, trekking through a mountain range in order to reach Zagreb. He had been lost without any form of communication, was malnourished, and exhausted from a lack of sleep. He came a long way, desperate to seek asylum in Croatia, but was incarcerated instead.

Upon his release from the Ježevo detention center, which only occurred once he had withdrawn his asylum claim, we met again. It was then, before his departure back to Albania, that he asked: »Is there a way I can help you?« I froze… Not because I thought I did not need help, obviously, I did (at the time, I felt as manipulated and harassed by the Croatian police and migration officers as he did when assisting him with the asylum claims), but—honestly speaking—I did not know how to reply. If caring is connected to privilege, what could I possibly ask of a person in such a precarious position? Still, the practice of radical care is an empowering act. No one can prescribe whom we can or cannot care for. Although I did not entirely succeed to help K., we were able to mutually empower each other by exercising our right to care as humans and as political subjects.

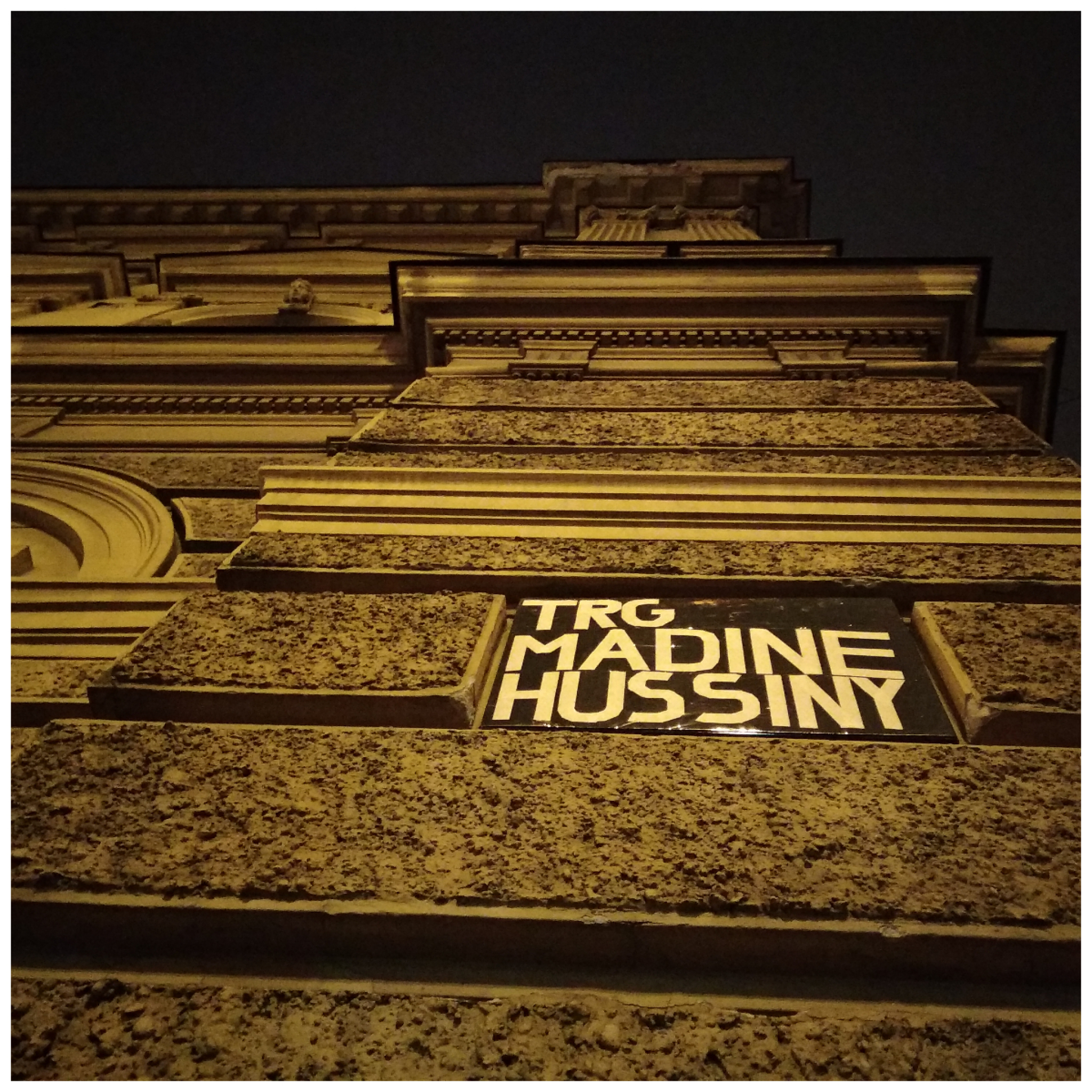

Renaming the Republic of Croatia Square into Madina Hussiny Square (2018) was an intervention performed by the Initiative for the Madina Hussiny Square in memory of Madina Hussiny, a young girl from Afghanistan whose tragic end was the result of a senseless persecution by the Croatian police. The (re)placement of the heat sheet, tape, and cardboard plaque with Madina’s name placed at the former Republic of Croatia Square was an act of uncompromised naming—a political, but also profoundly human gesture. It did not call for yet another reinterpretation of a historical event or figure, but was an immediate act of demanding accountability for actions committed and for the irreversible loss of life; because no one: no nation-state, government, military power, economy, or political regime has the right to decree one life valuable and another dispensable.

The encounters with Y., H. and K.—like with so many others—are a constant reminder of how every dangerous, life-threatening journey, every act of systemic violence, and every violation of human dignity endured by so many is, in fact, endured also for our own personal and political freedoms. With every contingent encounter, every boat departing, every plane deporting, and with every violent push-back, detention, incarceration, and torture testimony, we are called to join the liberation movement and its uprising.

I would like to thank Iva and Alex Masters for friendly proofreading.

Literature

Beroš, Ana Dana (2017): TRANS|MIGRANTNOST. Psihogeografije prijelaza [TRANS|Migration. Psychogeographies of the threshold]. In: Život umjetnosti 101 (2).

Free the Röszke 11 (2019): Szabadságot a Röszkei 11-nek! freetheroszke11.weebly.com [20.12.2019].

The Shining is an intervention performed by Selma Banich in cooperation with neighborhood inhabitants as an epilogue to the Communities of Care research project. Communities of Care was conducted by Selma Banich, Marija Borovičkić, Mila Čuljak, Ivana Rončević, and Ana Vilenica within the framework of Invisible Belonging, curated by Ana Dana Beroš. The project was a local, Zagreb segment of the international project Actopolis, produced by the Goethe-Institut and Urbane Künste Ruhr (2015–2017).↩︎

Some names in the article have been deliberately abbreviated to protect the identity of the people and also to put a graphic emphasis on ›light‹ interventions.↩︎

Action performed during the public presentation of the 101st issue of the journal Život umjetnosti (Beroš 2017).↩︎

Ahmed H. was convicted for ›terrorism‹ in Hungary, because he protested with thousands of refugees at the Serbian-Hungarian border crossing of Röszke in September 2015 (Free the Röszke 11 2019).↩︎